December 10, 2024

BEIJING/LANZHOU/URUMQI – Caring for livestock during the cold season in Northwest China has been modernized in recent years, with Beidou positioning, mobile support vehicles and real-time weather updates making the trek to winter pastures easier for herdsmen and animals.

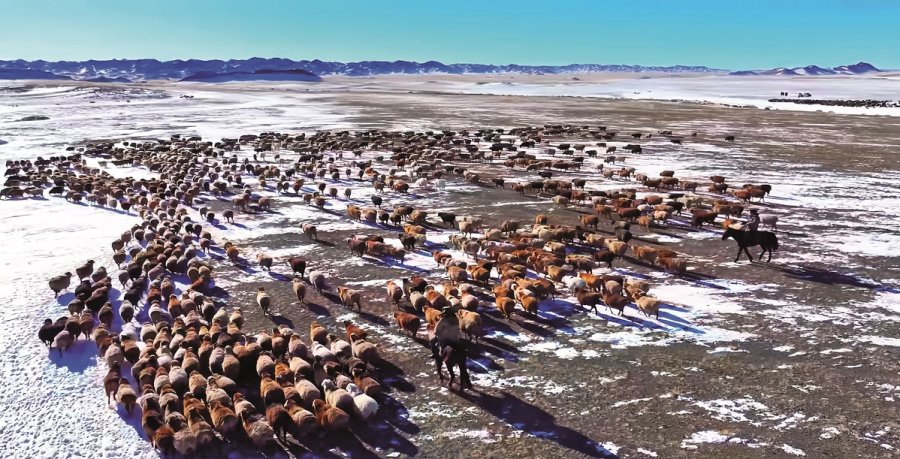

The sight of hundreds of thousands of yaks, cattle, sheep and camels migrating through high country has become one of the most colorful images marking the coming of winter.

However, in Sunan Yugur autonomous county in Zhangye, Gansu province, a rare sight could be seen this year. About 200,000 livestock were still grazing in the area on farmland rented by the herders as the winter closed in. The yaks and sheep were eating stalks left from the last corn harvest.

The move to keep them in the vicinity is being adopted across the county with the aim of boosting farm incomes while reducing environmental stress.

Gao Yongdong, 53, raises 200 yaks and about 20 sheep at Kangle town near the Qilian Mountains.

He paid 37,000 yuan ($5,102) to farmer Gan Junzhu to rent 13.33 hectares of farmland at the foot of the mountains for his livestock to feed on from October to next spring.

“My own grassland will be undisturbed and grow naturally so that the quality of grass next year can be improved,” he said.

The mountains, stretching over 800 kilometers, have a vast area of high-altitude grassland, with Yugur, Tibetan and Mongolian herdsmen living there.

In 2000, a handful of herdsmen in Sunan county voluntarily adopted the new model, and the practice of not moving livestock in winter has been increasing ever since.

Zhu Wenxin, head of the forage grass department of Zhangye’s animal husbandry and veterinary bureau, said in the past there had been an overgrazing problem due to the limited grass production in winter pastures. This affected the regeneration of grassland and damaged vegetation, he said.

“Using the new model, the grassland has a five-month break to recover,” Zhu said.

“The ample corn stalks in the fields serve as food, allowing livestock that would otherwise not have enough to eat during winter…to resist the cold and be fattened up instead. This has increased the sale price of yaks and sheep in the spring and is also good for livestock reproduction.”

For farmers who grow corn, the income from renting their fields for grazing is higher than selling the stalks, he added. “More importantly, after the yaks and sheep consume the stalks, they leave manure in the fields, which becomes organic fertilizer when the fields are plowed in the spring,” he said.

A police officer who helped a herder find a lost newborn lamb in the Bortala Mongolian autonomous prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, pets the animal. The mass migration of sheep in Altay prefecture, Xinjiang, is seen in the background. PHOTO: PROVIDED/CHINA DAILY

Financial windfall

Wang Dong, 55, a farmer from Majun village in Zhangye, said he starts planting corn around April 15 each year, and begins harvesting around Sept 20.

After harvesting his crops, he rents his corn fields to herdsmen from October to March, a commercial practice he has now done for three years.

“We have few livestock of our own, and the land would otherwise be unused. Renting it out to herders brings us additional income of 150 yuan per mu (0.067 hectares).”

This year, Wang rented all his 100 mu of land to Bai Zhengyuan, a herder from Mati village, Sunan.

In the past, Wang had sold the corn stalks to large-scale livestock farmers in the village for 100 yuan per mu, so renting the land to herders brings him an extra 50 yuan.

The manure left by the animals can be used as fertilizer, which means an additional 50 yuan per mu is saved on purchasing fertilizer, he said.

Bai and his family live close to the village. They use barbed wire to fence off the land and keep the animals penned in.

Wang said having the animals so close “doesn’t affect our daily lives or pose any harm to the elderly and children”, adding that he and Bai are good friends who talk a lot.

Police officers and herders work together to unload the sheep, increasing the efficiency of the migration. PHOTO: PROVIDED/CHINA DAILY

Fatter, healthier

Since 2000, the number of livestock grazing on natural grasslands in Sunan has decreased by 93,000 sheep every year on average.

This has resulted in 1.07 million mu of natural grassland in the Qilian Mountains having a “vacation” for nearly five months from the impact of grazing herds, according to the animal husbandry and veterinary service center of Sunan county’s agriculture and rural affairs bureau.

In 2022, the grass yield per mu on the county’s natural grassland increased by 20.6 percent compared with 2010, and the total coverage of pasture grass reached 78.2 percent, according to the latest data from the center.

There has also been significant growth in the utilization rate of crop residues in farming areas.

“Stalks have rich nutrients to fatten the livestock, increase wool production and increase the survival rate of lambs during winter,” said An Yufeng, director of the center.

“Although each sheep may incur an additional cost of 98 yuan when compared to transferring them to a winter pasture, the overall net income can still be raised by 28 yuan,” he said, adding that a herder can on average earn an extra 12,000 yuan in annual income.

The shortage of grass and lack of infrastructure at some winter pastures to keep the animals warm, as well as the risks of livestock deaths are additional costs herders can face if they shift their livestock, An said.

Last year, local farmers in the county received 68 million yuan in income by renting land to herdsmen.

“It also reduced the problem of air pollution caused by farmers burning crop residues, as well as the use of chemical fertilizers on farmland, thereby lowering agricultural costs,” An said.

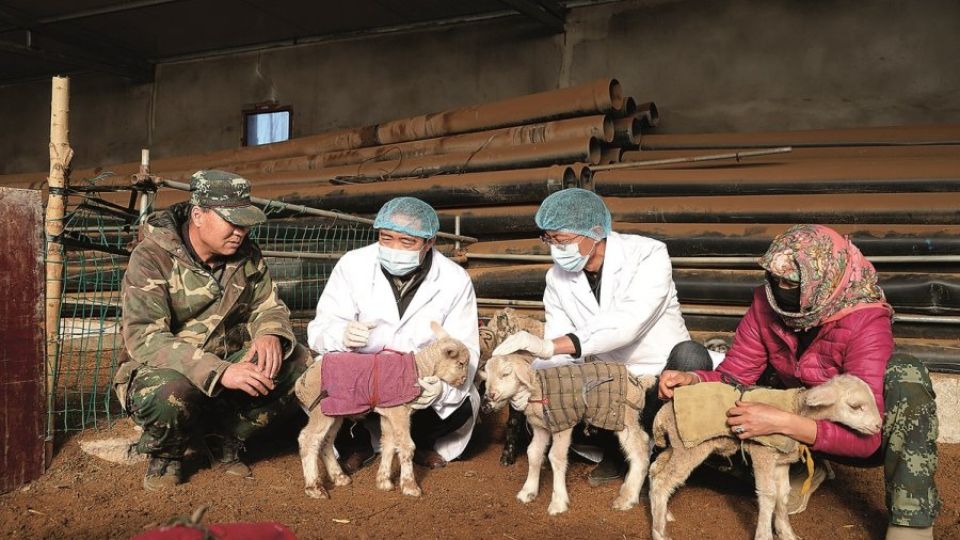

Since 2014, the local government has been recording livestock information and examining the animals’ health to prevent epidemics. This year, each herder’s family received a 1,000-yuan government subsidy, as well as gloves, washing powder, and disinfectants.

Police officers help herders count and corral the sheep during the migration in Bortala. PHOTO: PROVIDED/CHINA DAILY

Sticking to tradition

However, some herders choose to follow the old method of trekking their herds to winter pastures, believing in the adage of “survival of the fittest”.

In late November, 230,000 camels, cattle and sheep marched across snow-covered mountains from Jeminay county, Altay, Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, to winter pastures 100 kilometers away, forming a spectacular procession.

Azat Tospuhan and his younger brother took 200 sheep on the journey.

“We must reach our winter pasture before the heavy snow arrives to ensure a safe winter for the livestock. To prepare for this, we have stocked up on ample feed and forage and have warm shelters ready,” he said.

Special service vehicles nicknamed “mobile happy stations” were sent by the government along the route. The stations carried forage for the animals, and provided herders with hot water and meals, and devices to charge their mobile phones. Doctors were also available to check the herders’ physical condition and provide medication if needed.

“Along the way, we listen to the radio and check messages on our cellphones without worrying about running out of battery. We can take a rest if we want. The happy stations truly solve major problems we face during the migration,” said Bardihan Narenhan, a herder.

When they arrive at their destinations, herders can move into furnished accommodation with power, water and a mobile signal. Newly-built sheds also help protect livestock from snowstorm and wild animals.

A police car guides a convoy of livestock trucks on a winding road in Xinjiang. PHOTO: PROVIDED/CHINA DAILY

Tech-assisted migration

In recent years, more herdsmen in Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region have been using trucks for the migration to save time, improve efficiency, and protect both people and animals from extreme weather and other risks.

Badmal, a herder from Bayinbuluke town in Bayingolin Mongolian autonomous prefecture, was preparing to move to a pasture some 300 kilometers away in late November.

Shouting at and prodding the flock, the lambs were lined up and walked onto a truck with three decks.

In the past, it was a long and arduous journey to the pasture, but it now can be completed in a single day using trucks for transportation.

In another innovation, some sheep are fitted with positioning collars of Beidou Navigation Satellite System so that herders can check their real-time location on their mobile phones. This information can also be transmitted to the agricultural department’s big data platform.

An official talks to a herder about trekking livestock to winter pastures to ensure smooth operations on Nov 15 in Altay. PHOTO: PROVIDED/CHINA DAILY

By scanning the QR code on a small orange tag on a sheep’s ear, information such as its birth date and vaccination status can also be verified.

At Ili Kazak autonomous prefecture, 491 herdsmen and about 100,000 livestock from Huocheng and Yining counties set off in trucks in mid-November for winter pastures at Yalmut village, Wenquan county, Bortala Mongolian autonomous prefecture about 320 km away.

To ensure a safe journey, police officers set up checkpoints and safety warning signs at intersections.

At border police stations “herdsmen migration service points” offered instant noodles, milk, tea, and food.

Multiple county governments have also established a real-time information exchange mechanism, which promptly releases updates on personnel and vehicle movements, weather and road conditions.

“Township staff made arrangements for our migration. Weather warnings were posted in WeChat groups. Police officers escorted the convoy and provided hot water and food. We felt a great deal of warmth as well as convenience,” said Hababay Tohtibay, a herder from Yining county.