December 13, 2024

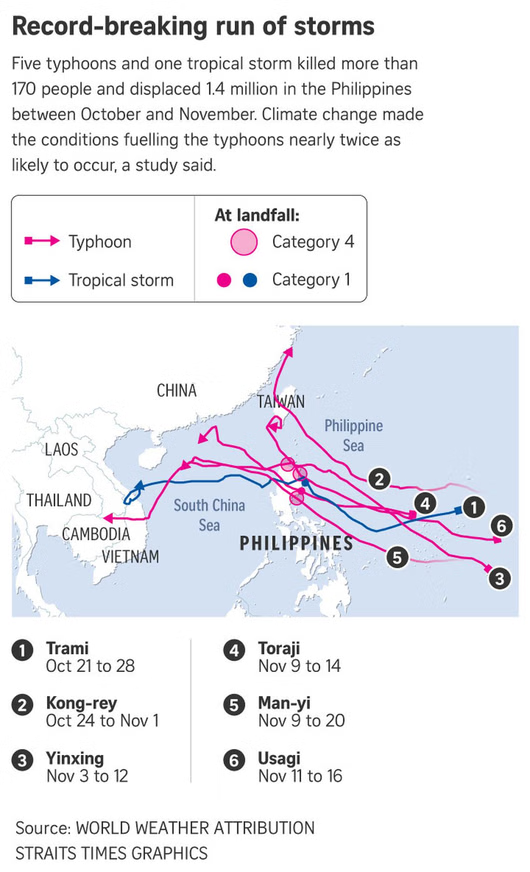

SINGAPORE – Climate change intensified an unprecedented six back-to-back storms that killed more than 170 people in the Philippines between October and November 2024, a study published on Dec 13 found.

Over the course of 23 days, the five typhoons and one tropical storm displaced 1.4 million people and caused severe damage to infrastructure and the loss of homes and crops, with early estimates of economic losses of nearly US$500 million (S$672 million).

The analysis by World Weather Attribution (WWA), an international scientific collaboration, found that more typhoons hitting the Philippines are reaching Category 3 to 5 levels, with 5 as the maximum, as fossil fuel emissions heat up the planet and change the climate.

The research team from the Philippines, Britain and the Netherlands found that climate change nearly doubled the likelihood of conditions that formed and fuelled the typhoons – namely sea surface temperature, sea level pressure, air temperature and humidity.

Using computer modelling, the researchers found that climate change has also made it 25 per cent more likely that at least three Category 3 to 5 typhoons will hit the Philippines in a year.

“The barrage of typhoons was supercharged by climate change,” said Dr Ben Clarke, a researcher at the Centre for Environmental Policy at Imperial College London and a co-author of the study.

“While it is unusual to see so many typhoons hit the Philippines in less than a month, the conditions that gave rise to these storms are increasing as the climate warms,” he said.

Dr Clarke added: “The analysis also found that the typhoon-favouring conditions will continue to increase as the climate warms, boosting the chances of destructive typhoons hitting the Philippines in the future.”

The study comes after the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service said on Dec 9 that 2024 will be the world’s warmest year since records began, with extraordinarily high temperatures expected to persist into at least the first few months of 2025.

Oceans have absorbed about 90 per cent of the excess heat produced by human activity, leading to an overall increase in sea surface temperatures.

Typhoons draw their energy from warm ocean temperatures as they form and grow, drawing up huge amounts of moisture. Increasingly warmer oceans are providing the fuel to create stronger storms and also increasing the amounts of rain they dump on land.

The Philippines is located in a part of the Pacific Ocean that generates about a third of all tropical cyclones globally.

“This November was unusually active and saw the occurrence of four named storms at the same time in the Pacific, the first time it has happened since record-keeping began in 1951,” said Dr Clarke.

The storms hit from late October to mid-November, just as the COP29 climate talks in Baku, Azerbaijan were getting under way. Five of the storms made direct landfall on Luzon, the most populous island in the Philippines.

Tropical storm Trami killed more than a dozen people in October as it unleashed a month’s worth of rain on the northern Philippines.

Within days of Trami sweeping through the Philippines came Super Typhoon Kong-Rey, which passed just to the north of Luzon before making landfall in Taiwan, where it killed at least three people.

A week later, Typhoon Xinying hit Luzon with winds of 240kmh, forcing the evacuation of 160,000 people.

“The Philippines experiences about six to eight landfalling tropical cyclones annually. Having five typhoons in less than a month was extraordinary, and our study found that climate change made them much more destructive,” said co-author Joseph Basconcillo, climatologist at the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration.

WWA has completed more than 90 studies around the world using peer-reviewed methods, analysing the possible influence of climate change on extreme weather events such as storms, extreme rainfall, heatwaves and droughts.

Its work has consistently shown that individual weather events can be linked to climate change, with some events becoming several times more intense due to its impact.

A WWA analysis published in October 2024, days after Hurricane Milton struck the US state of Florida, showed that global warming made the storm’s wind speeds about 10 per cent stronger and rainfall greater by between 20 and 30 per cent.

GRAPHICS: THE STRAITS TIMES