April 27, 2023

NEW YORK/LOS ANGELES — On Amazon.com’s U.S. website, many e-books are offered where the conversational AI model ChatGPT is listed as the author or as a coauthor. The genres include cookbooks and novels.

ChatGPT reads large amounts of text and other online materials, then generates text when prompted by a user. There is a risk of copyright infringement if phrases and whole sentences are generated that resemble those by famous authors or have appeared in news articles.

It is essential that checks be made at the time an AI-generated work is published, but it is not yet clear to what extent these checks have been made.

News/Media Alliance, a nonprofit organization of about 2,000 U.S. publishers, issued a statement on AI principles on April 20, saying, “The unlicensed use of content created by our companies and journalists by GAI [generative artificial intelligence] systems is an intellectual property infringement.”

It added, “GAI developers and deployers must negotiate with publishers for the right to use their content.”

Under U.S. Copyright Law, the use of copyrighted works for certain limited purposes such as for research, news reporting and education is permitted under the doctrine of “fair use” and therefore does not constitute copyright infringement. Yet, there has been no precedent as to whether the learning and creation of works by AI constitutes fair use, so using generative AI has continued without clear guidance as to whether what it produces might violate the law.

The spotlight has recently fallen on an ongoing U.S. lawsuit on this very issue.

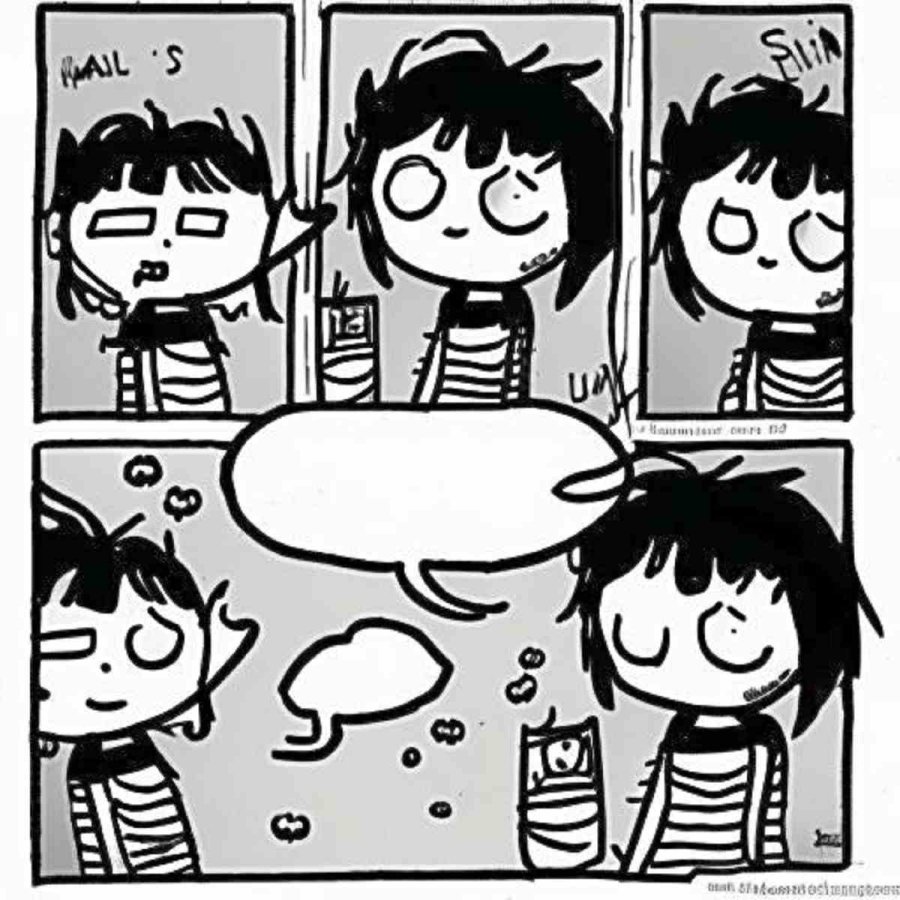

Cartoonist and illustrator Sarah Andersen, 30, and two fellow U.S. artists in January filed a class-action lawsuit over copyright infringement in a U.S. district court in California against several companies including Stability AI, Ltd., a U.K. startup that developed the AI image generator Stable Diffusion.

Stable Diffusion’s text-to image model is based on about 6 billion images and text datasets freely available through Laion, a German nonprofit organization. When users of Stable Diffusion indicate the style of a particular artist, the placement of people and other details, the system creates images that look as if they were made by the specified artist.

Sarah Andersen’s work

Courtesy of Sarah Andersen

Andersen claims that works created by generated AI should require consent from the original artist, a credit for the artist, and compensation for the artist.

In response to the lawsuit, Stability AI and the other defendant companies named filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, arguing that AI-generated images did not resemble the artists’ works and that the lawsuit did not identify specific images that were allegedly misappropriated.

In late October, Stability AI said it had raised $101 million from investors, valuing it at about $1 billion.

In the United States, IT giants and AI-related startups grew under loose regulations based on “neoliberalism.” Elon Musk, chief executive officer of Tesla, Inc. of the United States, recently held the same view as some others to call for a temporary halt to the development of cutting-edge AI on the grounds that it could have a serious risk to humanity.

Musk, however, then announced on April 17 that his company will launch a ChatGPT-like service. IT giants are now fighting for AI supremacy without a second thought.

The debate over the review of U.S. Copyright Law has not yet begun in earnest.

“It’s going to be a couple of years before we have real clarity from the courts as far as some of these [boundaries of AI and copyright],” said Juliana Neelbauer, a partner at U.S. law firm Fox Rothschild.

The United Kingdom, however, strictly regulates the scope of what can be collected and analyzed using AI systems, due to strong concerns that training AI systems violates copyright.

A work created by generative AI after Sarah Andersen typed her name into the system

Courtesy of Sarah Andersen

The U.K. government had announced a policy to deregulate the development of AI, but withdrew it after opposition from Parliament, which said the creative industries should not be put in jeopardy.

Andersen and the two fellow artists decided to file the class-action lawsuit after finding a Twitter post from a fan. In October last year, she received a peculiar image of a person with a pet holding an umbrella drawn with a familiar touch.

She was horrified when she detected her touch in the image, she said.

The image was said to have been created by typing her name into a generative AI system.

She then tried the image-generation AI by entering her own name and was able to have the system create an image in her own style. Appalled that technology that threatened artists’ careers was out there without sufficient regulation, she decided to take action.

The artists’ argument is that their data was being used by Stable Diffusion without permission. They could not overlook this current situation in which they are not being paid for their work used to train the AI system.

In February, Getty Images Inc., which sells photos and videos to corporations and media outlets around the world, also filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Stability AI, alleging that it used more than 12 million Getty photos without permission.

Laion, which is a nonprofit organization, can collect copyrighted data for research purposes. However, given that for-profit Stability AI is giving support to Laion, Stability AI’s use of the data is highly questionable.

Andersen is outraged that Stability AI is making money by exploiting a loophole in the law that allows for-profit companies to take advantage of a special exemption for NPOs.

Andersen said the companies involved in generative AI are not interested in protecting the rights of artists. The only way to get them to listen to artists is through legal action, she said.

Sarah Andersen

The Yomiuri Shimbun