September 16, 2022

MANILA —There is “no genuine domestic investigation” of crimes allegedly committed by the government in the conduct of Rodrigo Duterte’s campaign against illegal drugs.

This was stressed by victims’ relatives last year as they asked the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor to resume its investigation on the government’s controversial anti-drug crackdown.

It was on Nov. 10, 2021 when the then Duterte administration, through its ambassador to The Netherlands, requested that the ICC defer its investigation of crimes related to the “war on drugs” that were allegedly committed from 2011 to 2019.

The government had stressed that this was to give way to domestic investigations, saying that the Philippines was investigating or has investigated individuals involved in alleged crimes against humanity committed in the course of the anti-drug campaign.

But while ICC chief prosecutor Karim Khan initially suspended the investigation on Nov. 18, 2021 to assess the government’s request, he formally asked the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber on June 24 for permission to resume it.

Last Sept. 8, Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra said his office, which represents the Philippines in the proceedings, asked the ICC to deny Khan’s request, stressing that the ICC has no jurisdiction over the Philippines.

Last Aug. 1, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. said the Philippines would not take part in the ICC process: “We’re saying that there is already an investigation going on here and it’s continuing, so why would there be one like that [in the ICC]?”

Recently, as he stressed that there was no need for ICC investigators to come, he said the only way for them to be welcome would be “if the whole system collapses” or “if we have a war here”.

Gov’t not doing enough

This, even if the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) said the government should do more in its investigations, especially on crimes allegedly committed in the campaign against illegal drugs.

The UN rights office said that while the Philippine government took initiatives to advance accountability for rights violations, “access to justice for victims […] remained very limited”.

It stressed that institutional and structural lapses, like limited oversight of human rights investigations and inadequate investigation capacity and of inter-agency cooperation, have yet to be addressed.

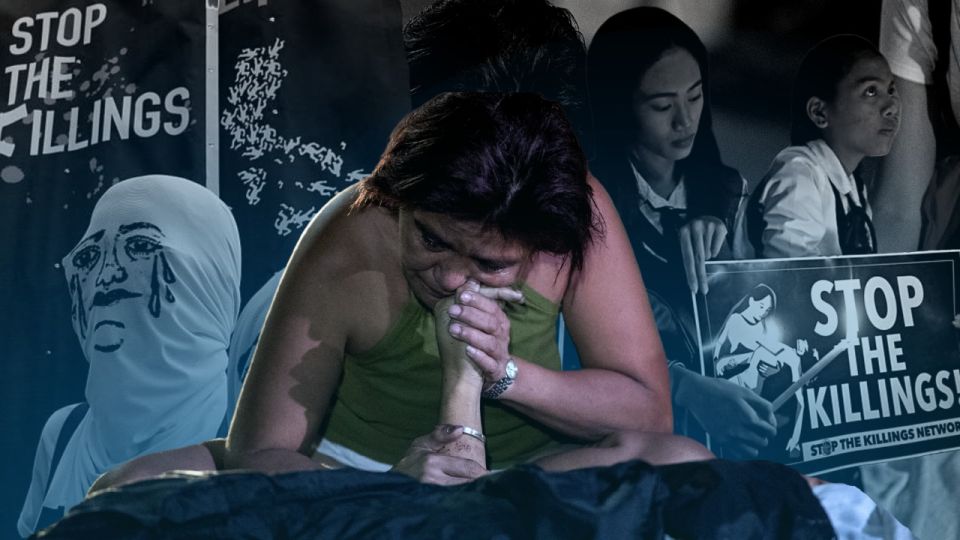

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

Limited forensic capacity and protracted judicial processes should also be addressed, the OHCHR said. Inadequate victim and witness support and protection and fear of reprisals also affected victims’ engagement.

The office released its report on Tuesday (Sept. 13) as mandated by a UN Human Rights Council Resolution that offered technical cooperation and capacity building for the protection and promotion of human rights in the Philippines.

To recall, the council, through that resolution, encouraged the government to address issues raised in a High Commissioner’s report and the remaining challenges related to human rights in the Philippines.

Still elusive

Based on data from the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), 6,252 individuals had been killed in Duterte’s anti-drug campaign between July 2016 and May 2022, saying that there had been a decline in the killings resulting from police operations.

It said 448 persons had been killed in 2020, 214 in 2021, and 27 from Jan. 1 to May 31 this year. Likewise, the 239,218 police operations that were conducted in the past six years resulted in the arrest of 345,216 individuals.

But rights groups had stressed that the death count could be higher, saying that since 2016, the year Duterte won the presidential election, over 30,000 had already been killed in police operations and vigilante-style killings.

The OHCHR noted that while the government took initial steps toward investigating some of the killings in the context of the police crackdown on illegal drugs, “these steps did not result in convictions.”

It was in June 2020, when Guevarra, who was still then the secretary of justice, announced the establishment of an Inter-agency Review Panel (IRP) to review 5,655 deaths.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The UN rights office, however, said the DOJ “encountered obstacles to its review, including the availability of and access to relevant records”. Last month, Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla said the DOJ will get case files from the police.

The DOJ had reviewed some cases as the Philippine National Police, which initially committed to releasing more than 60 case files, only provided 52. The findings were handed to the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) for criminal investigation.

No convictions yet

Last Aug. 3, the government said 250 new cases related to the deaths, which resulted from police operations in Central Luzon, were reviewed by the IRP and that the findings were also handed to the NBI.

Then on Aug. 17, the OHCHR said Remulla informed diplomats that seven cases had been filed for prosecution involving 25 police officers—two of these cases are now pending in court where nine have been indicted.

Likewise, last year on Aug. 25, seven police officers of the San Jose del Monte police station in Bulacan province were charged with the arbitrary detention and murder of six men in the course of a police operation in 2020.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The six were said to have been detained as they passed by the house of a suspect and were subsequently killed. While police claimed they resisted arrest, the investigation revealed a photo of the six in the police station, with their hands tied behind their backs.

But despite this, the OHCHR stressed that as of the end of July 2022, none of the initial 52 cases that have been reviewed last year, had resulted in convictions, saying that transparency and public scrutiny in investigative processes remain a challenge.

To address concerns, it recommended that the IRP, which was established by the DOJ, “should accelerate its review of all killings related to the government’s war against illegal drugs.”

The panel, the UN rights office said, should also make certain that relevant findings are acted on promptly and efficiently, including through internal administrative and criminal processes.

This, as the OHCHR noted in its report that the government said 67.69 percent of the drug cases filed from July 2016 to July 2022 all over the Philippines are yet to be resolved.

‘No intent to solve’

Last April, Dr. Raquel Fortun, a well-respected forensic pathologist, said the then Duterte administration had “no intent” to solve the deaths that resulted from its bloody crackdown on illegal drugs.

This, as her forensic investigation of the remains of some of the victims of the controversial war revealed irregularities, saying that falsifications in the death certificates of the victims were committed.

The forensic examination, which involved victims who died from 2016 to 2017, was made possible through Fr. Flavie Villanueva’s “Project Arise” that was initiated to assist relatives in their struggle for justice.

Fortun had said she examined the remains of 46 people killed in the campaign against illegal drugs and found that the cause of death of some had been falsified to show they died of “natural causes”.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The death certificates of seven of the victims, who had multiple gunshot wounds, indicated they had died of hypertension, sepsis, pneumonia or heart attack. Out of the 46 bodies, 24 to 32 bore gunshot wounds in the head.

Guevarra had said the alleged falsification of death certificates as a possible coverup was part of the DOJ review and that “the original problem that we encountered was the absence of a copy of the death certificate in some records or files that we reviewed”.

War on poor

Fortun had concluded that based on the economic backgrounds of the victims, the government’s controversial crackdown against illegal drugs targeted “the poorest of the poor”.

Based on a survey by the Social Weather Stations (SWS) in 2017, most Filipinos agreed that rich drug suspects get to live while the poor die. Only 23 percent disagreed, and 17 percent were not certain of their view.

Then in 2020, results of a survey by the SWS said 76 percent of Filipinos believed that “many” violations were committed in the drug war—33 percent said there were “very many” and 42 percent said “somewhat many”.

Last Sept. 8, the New York-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) said it has found “no compelling evidence” to show that the state is thoroughly investigating the crimes against humanity allegedly committed by the previous administration.

“Since the Philippines first sought a halt to the prosecutor’s investigation last November, HRW has monitored the situation and found no compelling evidence that the government was seriously investigating these cases, let alone prosecuting those responsible,” said HRW senior researcher, Carlos Conde.

He stressed that the “killings are continuing and impunity for police officers and others implicated in these abuses by all accounts remains intact”.

Review policies

The OHCHR called on the government to revise drug legislation and policies in line with human rights standards and international guidelines on human rights and drug policy.

It said the government should also revisit the mandatory penalties for drug offenses and to consider the decriminalization of drug possession for personal use.

The report also recommended the passage of proposed legislation on human rights defenders, and implement measures to protect civic space for them to be able to play their legitimate role securely and without reprisals.

This, as it noted that it continued to receive reports of killings, arbitrary detention, and physical and legal intimidation against human and environmental defenders, journalists, lawyers, labor activists and humanitarian workers.

“They are often targets of ‘red-tagging,’ a tactic deployed to accuse individuals of fronting for the [Communist Party of the Philippines-New People’s Army]. This continued to put human rights defenders at risk, hampering legitimate human rights activities while eroding trust between the government and civil society actors,” it said.

“Critically, it calls on the government to take all necessary steps to ensure the continued independence of the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines, including through a transparent and consultative appointment process for Commissioners in line with the Paris Principles.”