December 5, 2024

MANILA – When news began spreading that President Yoon Suk Yeol was placing South Korea under martial law on Dec 3, I was reminded of my own experience as a child growing up in a country ruled for years by an autocrat.

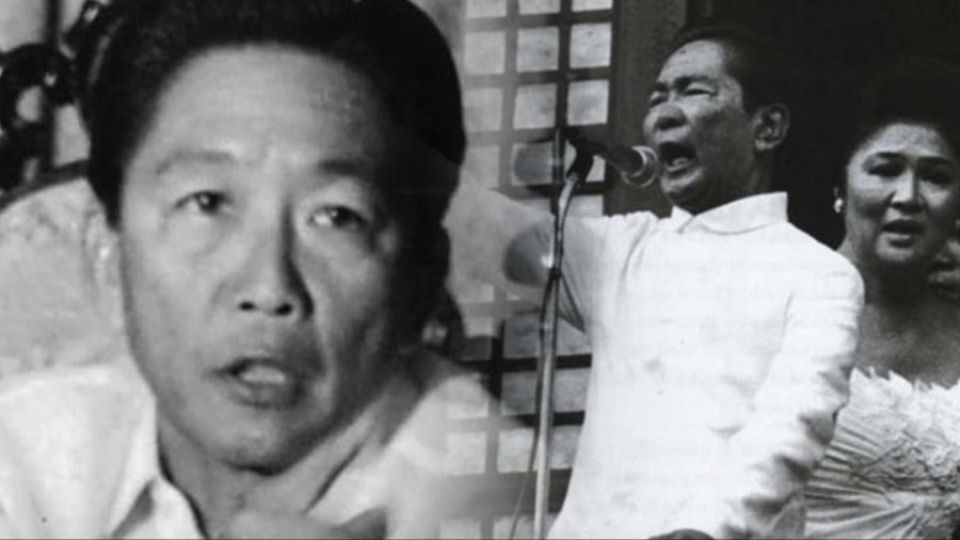

I was three years old when then President Ferdinand Marcos placed the Philippines under martial rule in September 1972. By the time he lifted it in 1981, I was 12.

My memories of martial law are a mixture of innocence and menace: playing hopscotch with my friends, and being sternly told to stay away from a neighbour who was with the Metrocom, a special police unit known for torturing and making activists disappear.

I remember nights when my father and I would sleep amid bags and sacks of rice and vegetables on the roof of a bus that had to stop by the roadside because it was already midnight and curfew had set in.

Curfew was from midnight to 4am, and anyone caught loitering in the street during those hours was arrested, taken to a sprawling military camp and held overnight – longer if he or she did not have a good reason to be out and about when the person was supposed to be home.

I remember hearing a story about this TV host and comic who rubbed Marcos the wrong way when he made fun of the martial law motto: Sa ikauunlad ng bayan, disiplina ang kailangan (For national progress, we need discipline).

The comedian joked on TV: Sa ikauunlad ng bayan, bisikleta ang kailangan (For national progress, we need bicycles).

He was promptly picked up by the police, and made to do laps on a bicycle around an oval track inside a police camp in Manila for the entire day.

I remember the rousing marching song Bagong Lipunan (New Society) that Marcos coerced a national artiste to compose to propagate his conviction that martial law was a time of renewal, hope and progress.

It was inescapable. It was played everywhere – in schools, cinemas and government offices – providing a discordant backdrop to a nation that was, in reality, plagued by state-sponsored death squads, institutionalised kleptocracy and crushing poverty.

When it hit home

But I was a child then, and martial law for me was just part of growing up in the 1970s. There was nothing political about it.

We were poor but everyone else around us was poor.

We lived in a unit on the second floor of a row of decrepit two-storey apartments that our landlord somehow managed to build on land he did not own.

It was in the middle of thousands of shacks that were really nothing more than cardboard, plywood and tin sewn together by nails, chicken wires and adhesive tapes, and covered with galvanised steel held in place by cement blocks, used tires and other heavy debris.

I had always believed, with a child’s logic, that you were poor because you were lazy, not because of Marcos.

But then, there was a time when his wickedness hit home and his martial rule felt real.

At the time, the TV networks ran a slew of robot-themed manga shows that were so popular that the streets would be empty by 6pm as children watched their favourite android heroes battle space aliens.

It was a welcome relief from all the government propaganda and inane noon-time shows and benign American sitcoms that we were seeing on TV.

There was one show in particular – Voltes V – that told the story of an oppressed people rising up to overthrow a repressive, brutal, autocratic regime.

Marcos must have felt alluded to. So, he had Voltes V and all the other robot shows like it canned.

I was so upset that I remember grabbing a red marker off a table, heading to a construction site, and writing on an upright plywood: “Marcos, ibagsak!” (Down with Marcos). That was in 1979.

By 1981, martial law was over. By 1986, Marcos was gone from office.