January 8, 2025

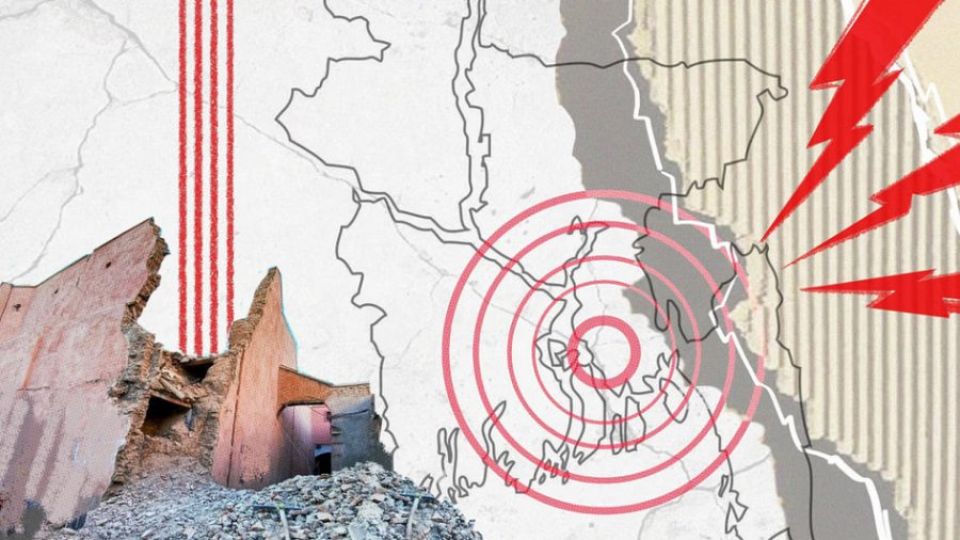

DHAKA – Having experienced two earthquakes in the span of a single week, an obvious question looms – are we taking this silent threat seriously enough?

Luckily, none of the two earthquakes — one on January 3 with a moderate magnitude of five that originated in Myanmar and another yesterday morning with a 7.1 magnitude originating in Tibet — were close enough to affect us.

Yesterday’s quake had its epicentre near the Nepal-Tibet border and reportedly killed at least 126 people. Dhaka residents woke up to the tremors early in the morning, content with the thought that the quake was not big enough in the country.

Experts, however, say that Dhaka sits precariously on a seismic time bomb.

Research indicates that the Indo-Burma subduction zone, encompassing Sylhet and Chattogram, is accumulating strain capable of generating a significant seismic event, with the capability of releasing the energy of up to a magnitude of eight.

Another very active zone is the Dauki fault, which has been associated with several large earthquakes. It is believed to have ruptured three times in the past millennium, with significant events occurring in 840, 920 and 1548 and possibly the 1897 Assam earthquake, which had a magnitude of eight or more.

Smaller tremors occur in this region regularly — 550 earthquakes with a magnitude of four or above have struck within 300km of Bangladesh in the past decade. This comes down to an average of 55 quakes per year, or four per month. On average, there are earthquakes near Bangladesh every six days.

Experts say these small seismic events can be a warning sign of a bigger earthquake in regions with active faults, such as the Dauki fault or the Indo-Burma subduction zone.

The Great Assam Earthquake of 1897 shook the Indian subcontinent, reaching parts of Dhaka. More than a century later, experts warn that the region is overdue for another seismic event — one that could have devastating consequences for the Bangladesh capital’s 22 million residents.

As one of the world’s most densely populated cities, Dhaka is alarmingly ill-prepared to face such a disaster.

While minor tremors have been felt over the years, the city’s collective response has been nothing more than a fleeting concern. It is no longer a question of what will happen if an earthquake hits, but when it hits.

With dense urbanisation and poorly enforced building codes, the city is at risk of catastrophic damage in the event of a major quake.

Dhaka is more vulnerable to earthquakes due to its geological location, and human and economic exposure. According to the earthquake disaster risk index, the capital tops the list of the 20 most vulnerable cities in the world.

Even though Bangladesh achieved remarkable success in disaster management, especially managing events like cyclones and floods, the scenario would be different in case of a catastrophe in Dhaka and require meaningful government attention.

According to experts, the government should conduct extensive mass awareness programmes among citizens with regular earthquake drills; enhance children’s education about natural disasters using digital platforms; ensure volunteer training; and form a coordination platform with government and non-government agencies for rescue operations.

Also, as part of long-term measures, the government must enforce the proper implementation of the National Building Code. If needed, the code should be updated by incorporating a proper implementation plan.

We can no longer afford to be complacent.

The risk grows with every single day of delay. Earthquake drills, stricter building codes, and public awareness campaigns are no longer optional — they are a necessity.

The time to prepare is now, before it’s too late.