April 5, 2023

BANGKOK – A Chinese official in a Mekong River intergovernmental body has warned against jumping to conclusions about data on the distressed waterway, saying that politics may get in the way of closer cooperation between upstream and downstream countries along the waterway.

“Some parties start with preconceptions, and even come to a conclusion before they analyse the data,” Mr Hao Zhao, secretary-general of the Beijing-based Lancang-Mekong Water Resources Cooperation Centre, told The Straits Times in an interview on Monday.

He was speaking on the sidelines of the Mekong River Commission (MRC) international conference in Vientiane, Laos.

The conference preceded the MRC Summit, which starts on Wednesday.

Data is merely a tool for further inquiry, he said, referring to the United States-backed Mekong Dam Monitor run by the Stimson Centre which uses remote sensing and satellite imagery to keep track of dam operations and water levels along the waterway.

Chinese dams have been accused of devastating the river by withholding water upstream, an allegation which Beijing has denied and attributes to US bias.

“If you start with preconceptions and identify someone or some country as the guilty party, you will not reach a scientific conclusion,” said Mr Hao in Mandarin.

While technical experts on the ground may concur with their interpretation of the problem, “some incorrect understanding and incorrect reports cause the people to form certain opinions, which forces governments to declare (one party) wrong”, he said.

“In reality, this is not the case and it will affect future cooperation between upstream and downstream countries.”

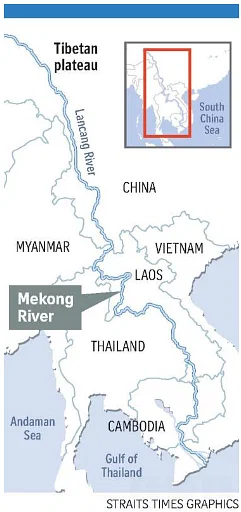

The 4,900km Mekong, which originates in the Tibetan Plateau, is South-east Asia’s largest river and runs through China – where it is called the Lancang – to Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam before it opens up into the sea.

Climate change and rapid dam-building along its mainstream and tributaries have threatened its fisheries as well as blocked the passage of silt needed to regenerate the environment downstream.

The MRC is an inter-governmental body comprising Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand established in 1995 to manage sustainable development of the downstream river basin.

China – which has been accused of holding other countries hostage through the way it runs its 11 hydropower dams upstream – bankrolled the creation of the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) in 2016.

This mechanism includes the four MRC countries, as well as China and Myanmar, and covers economic and agriculture-related cooperation, apart from those relating to water.

There are more than 100 dams on the Mekong’s tributaries as well as mainstream, including those spread across Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

Laos, in particular, has pursued a development model based on the export of hydropower to countries like China, Thailand and even as far as Singapore. Its projects have raised concern in Cambodia and Vietnam, which is struggling with saltwater intrusion during the dry season.

In an address in Vientiane on Monday, Dr Anoulak Kittikhoun, chief executive officer of the MRC secretariat, painted a dire picture of the Mekong, saying that sediment-trapping and sand-mining have reduced sediment transport by 60 per cent to 90 per cent.

Meanwhile, drought frequency has increased from 2010 to 2020 compared to the previous decade.

A joint study is being conducted by all six countries along the Mekong to examine changing hydrological conditions along the river and propose adaptation measures.

Dr Anoulak told ST that different countries have different views about what is causing changes in the river.

“The joint study is to build this common understanding,” he said. “It takes time.”

The idea is to look at all the parties’ available data and “hopefully (arrive at a conclusion) that it’s producing roughly similar trends”. This would then allow them to focus on the recommendations on what to do next.

Mr Hao told ST that there is room for greater coordination in the operation of all the dams along the Mekong.

Upstream reservoirs, for example, can release water in a manner and according to a schedule that would be beneficial to those downstream.

“If all the (Mekong) basin countries can achieve a reasonable consensus on water release, it would lead to a larger scale and better management of the infrastructure,” he said.