June 14, 2022

MANILA, Philippines—The prevalence of child stunting in the Philippines was 30.3 percent in 2018 and the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) said then that to reduce it to 21.4 percent by 2022, a 2.2-percentage point yearly decrease is needed.

The problem, however, is that stunting has become a silent pandemic, the World Bank said, stressing that in 2019, 29 percent—one in three Filipino children aged five years old and below—had stunted growth.

Its 2021 study, “Undernutrition in the Philippines: Scale, Scope, and Opportunities for Nutrition Policy and Programming”, revealed that for nearly 30 years, “there have been almost no improvements in the prevalence of undernutrition.”

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The Philippines, the World Bank said, is fifth among countries in the East Asia and Pacific region with the highest prevalence of stunting and is among the 10 countries all over the world with the highest number of stunted children.

It said that in 2019, the prevalence of underweight and wasting was 19 percent and six percent, respectively, stressing that based on the classification of undernutrition rates, the prevalence in the Philippines is of “very high” public health significance.

This was the reason that the Philippines, weeks before President Rodrigo Duterte steps down from Malacañang, will borrow $178.1 million from the World Bank to improve nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions.

The Washington-based multilateral lender will take into consideration on June 22 the said loan, which is intended to fund a multi-sectoral nutrition project that will be implemented by the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), to be headed by radio personality Erwin Tulfo, and the Department of Health (DOH), whose next head is yet unknown.

Looking back, the government, in 2021, was looking to tap the World Bank for a $200-million loan to improve nutrition programs, especially in local government units (LGUs), by having these components:

• Primary Health Care Integration: $127.3 million

• Community-Based Nutrition Service Delivery: $62.1 million

• Strengthening Lead Implementing Agencies: $10.6 million

The objective of the latest project, the World Bank said, is “to increase the utilization of a package of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions and improve key behaviors and practices known to reduce stunting in targeted LGUs.”

‘Impedes development’

Stunting, which is defined as impaired growth and development because of poor nutrition, is “one of the most significant impediments to human development,” affecting 162 million children below the age of five all over the world.

The World Health Organization said it is largely an irreversible outcome of inadequate nutrition and repeated bouts of infection during the first 1,000 days of a child’s life. As a result, retarded children do less well in school and earn lower wages as adults.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

It said that by 2025, if the current trend persists, more children—127 million—will be retarded: “With the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a possibility that more children will be stunted if there are no mitigating measures put in place.”

The United Nations Children’s Fund stressed that in the Philippines, in the last 15 years, little progress has been made to reduce stunting despite good economic growth and increased health budget.

The World Bank said in its study that one of the “basic determinants” of undernutrition is “governance structures,” saying that it likewise poses challenges for efforts to combat stunting.

It explained that municipalities, especially those with a high prevalence of childhood undernutrition, face several problems in the effort to implement nutrition interventions.

The primary problems, it said, are limited resources for nutrition programs; the lack of a full-time provincial, city, or municipal nutrition action officer; and the scarcity of health personnel.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

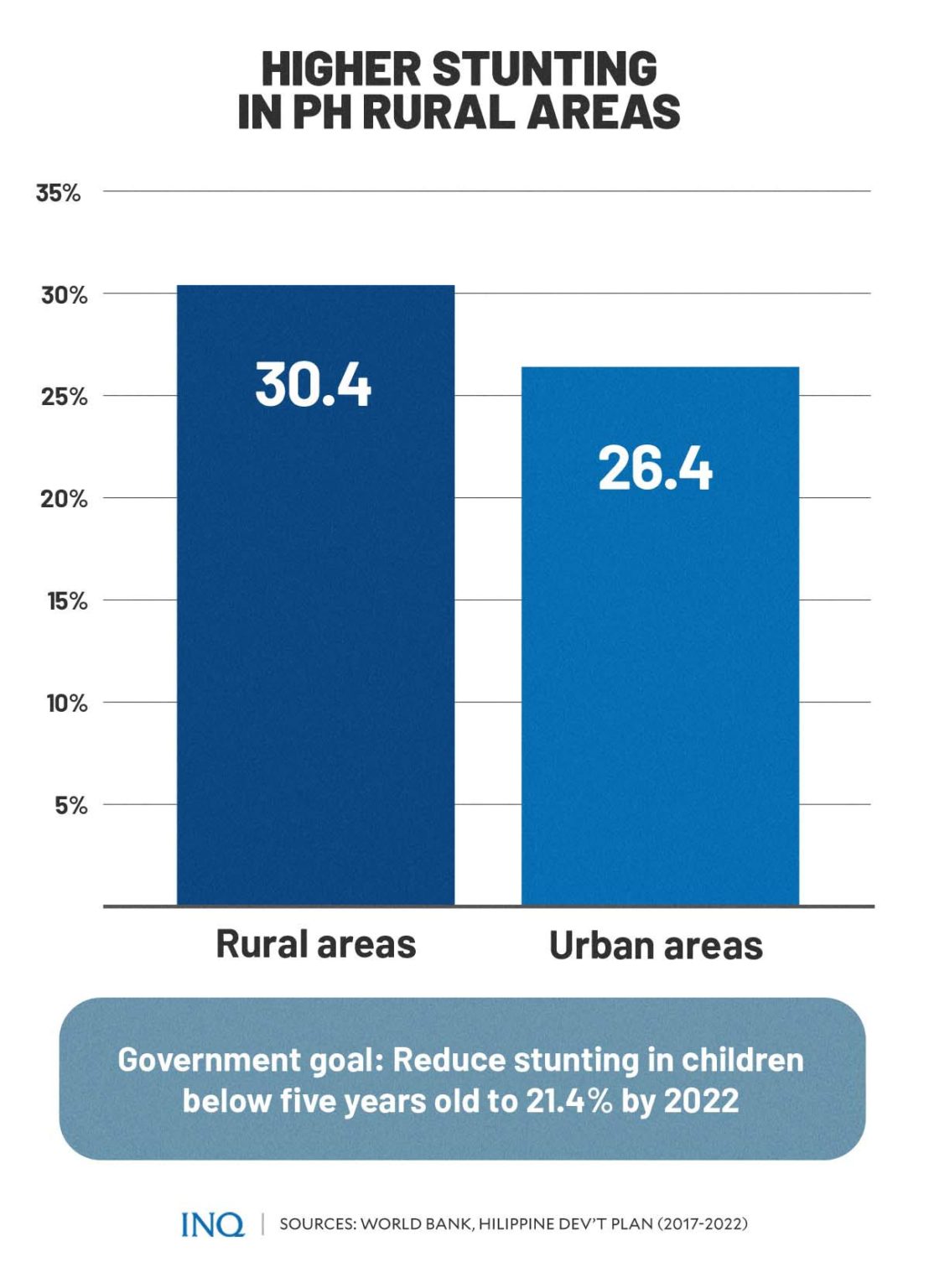

Based on the results of the 2019 Expanded National Nutrition Survey of the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI), undernutrition rates were higher in rural areas (30.4 percent) than in urban areas (26.4 percent).

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

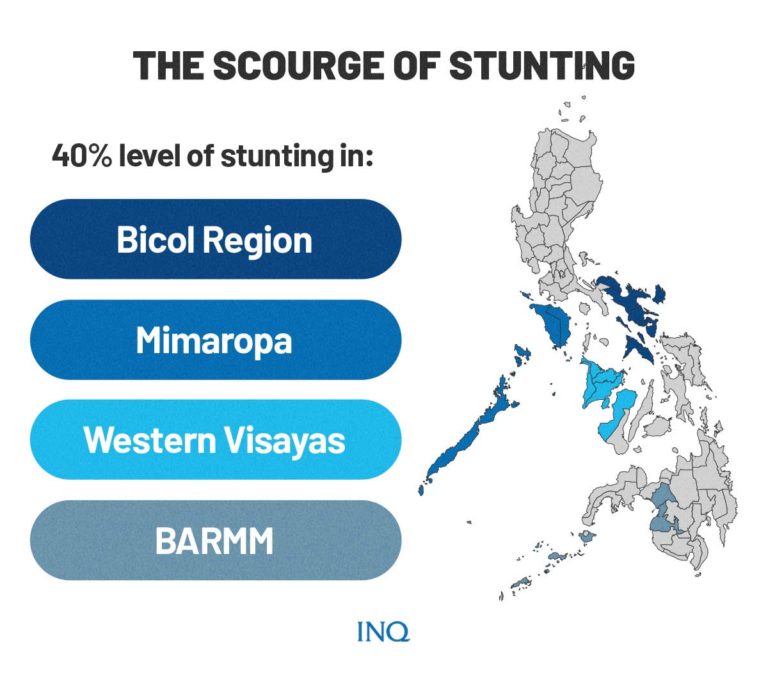

The World Bank likewise said that there are regions with levels of stunting that exceed 40 percent of the population of children below the age of five:

• Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao: 45 percent

• Mimaropa: 41 percent

• Bicol Region: 40 percent

• Western Visayas: 40 percent

• Soccsksargen: 40 percent

‘We need help’

Last March, the DOST asked the private sector for help, saying that the government cannot shoulder the responsibility of addressing the problem of malnutrition alone.

The department said the Philippines needed an estimated P6.5 billion to help 3.64 million stunted children who are six months to three years old: “To help resolve the country’s problem […] we need the support of civil society and the private sector.”

The FNRI, which has been implementing the Malnutrition Reduction Program since 2011, said a child needs one pack of DOST-developed complementary food daily. A pack is worth P15.

This translates to P54.6 million every day to feed beneficiaries for 120 feeding days. Currently, the DOST-FNRI, through its existing complementary food production facilities, can only cover 2.04 percent of this projected demand.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

For interested private sector partners, the DOST-FNRI developed these packages that they could buy for their Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives:

• Package 1: P120,000 will benefit 50 children for 120 feeding days

• Package 2: P180,000 will benefit 75 children for 120 feeding days

• Package 3: P240,000 will benefit 100 children for 120 feeding days

• Package 4: P2.25 million for the provision of equipment needed to produce complementary food that was developed by the DOST-FNRI

This, as the first 1,000 days of life, or the period when infants and young children go through rapid growth and development, make them susceptible to infections if they are undernourished.

“Any impaired physical and mental development in this critical phase is irreversible. This period is the ‘window of opportunity,’ when nutrition intervention is best provided. This crucial period is the best chance to help save our children,” the DOST said.

Problem likely to persist

The World Bank said the social and economic standstill triggered by the COVID-19 crisis posed grave risks to the nutritional status and survival of young children, stressing that initial indications showed that hunger in the Philippines rose sharply in 2020.

Two years into the pandemic, 3.1 million Filipino families—12.2 percent—experienced hunger in the first three months of 2022, the Social Weather Stations (SWS) said.

The 12.2 percent is 9.3 percent—2.4 million families—who experienced “moderate hunger” and 2.9 percent—744,000 families—who experienced “severe hunger”.

This, as the SWS said that in the first quarter of 2022, 43 percent, or 10.9 million Filipino families, considered themselves “poor,” higher than the 10.7 million in December 2021.

The World Bank said one of the most important basic reasons for health deficiency is poverty.

In the Philippines, 42.4 percent of children from households in the poorest quintile are stunted compared with 11.4 percent of children from households in the wealthiest quintile.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund, the Philippines loses P224 billion yearly because of undernutrition. For each P49.75 invested in the nutrition program, the economy will save P597 in the forgone earnings and health expenditures.