March 20, 2023

ISLAMABAD – CAN you imagine the desperation that would lead you to poison your wife and daughters — the youngest only two years old — with copper sulphate? High inflation and the inability to make ends meet led a man to do this in Karachi’s Surjani Town on Friday. While his suicide attempt failed, he lost his two-year-old child, and his four-year-old was left in a critical condition.

This family is not the first to succumb to raging inflationary pressures. The list is a macabre one — a man seeking to escape poverty by jumping into a canal with his four-year-old daughter in Muzaffargarh; a labourer from Narowal also choosing to drown in a canal with his two children rather than continue to battle penury.

These are among the few cases that are reported as suicides. Accurate reporting on suicides is almost impossible to come by in a social context where the desperate act is ridden with social and religious taboo. But anecdotal evidence is mounting that there is a plague of depression and anxiety fuelled by soaring food prices and the stalling economy. Sindh’s commerce minister last month raised alarm bells about growing suicide rates among the poor.

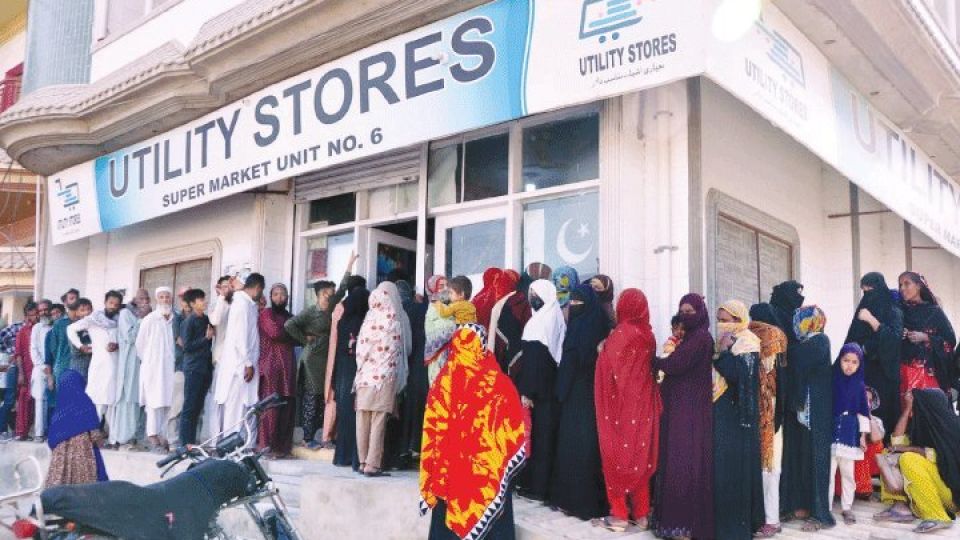

Though unimaginably tragic, such a trend seems inevitable. According to BISP programme data, more than 25 million families — amounting to 153m people — are getting by on less than Rs37,000 per month, the equivalent of $0.73 per person per day. This while weekly inflation is surging well over 40 per cent — and on the heels of last year’s floods that pushed 33m people into poverty, and which threaten to drag an additional 9m people into poverty this year, according to UNDP research. More than half the country’s population faces either moderate or serious food insecurity.

When the pie shrinks, it shrinks for everyone.

But you may have missed these suicide stories and horrifying statistics. They are unfortunately relegated to the back pages or late-night tickers while the shenanigans of our mainstream political parties dominate news headlines. But Pakistan is now at the tipping point where the shocking and callous disconnect of our elite politics is in danger of making the democratic system completely irrelevant.

While social media feeds and news cameras flit between Zaman Park and the Judicial Complex, little attention is paid to the plight of millions of Pakistanis who would rather submerge themselves in polluted canal waters or ingest copper sulphate than endure another day in the land of the pure. Sadly, there is no Toshakhana for the country’s masses to plunder when all other hope is lost. And as academic Arsalan Khan pointed out in a pithy tweet, the real horror is that it makes no difference which party comes out on top — Pakistanis still suffer.

The clear shift in Pakistan to ‘each man (or elite institution) for himself’ approach could not be more clear than in the juxtaposition of the attempted suicide/killing in Surjani and the theatrical, but ultimately navel-gazing chaos at Zaman Park. But it is becoming apparent in all aspects of politicking, policymaking and resource allocation.

Take, for example, last week’s news that the Punjab government is handing over agricultural land to the army to manage and make more productive with the help of the private sector. A trifecta of entitled elites will benefit from this absurd arrangement, but there seems to be little thought for the welfare of local communities or seasonal pastoralists that may rely on that land — or indeed for the land itself, which may not benefit from commercially driven overexploitation.

The growing number of suicides driven by hunger and poverty should dispel several myths that have bred Pakistani complacency over recent decades. First, that the ethnolinguistic, tribal and feudal nature of our politics means that politicians inherently draw on grassroots support, and so will take care of their constituents — in the name of retaining loyalty, if not as a public service.

The other is that Pakistan is among the most philanthropic countries in the world, and that informal charitable giving can substitute for a functioning social welfare state. The fact is, Pakistan is fast slipping out of global giving indices as even middle and upper-middle classes feel the pinch and are less forthcoming with donations. When the pie shrinks, it shrinks for everyone.

At some point, desperate Pakistanis will clue into the fact that the new rules of the game are personal survival at the expense of others. In other countries, at other times, such realisations have given rise to major — often left-wing — political movements. Sadly, the only groups in Pakistan poised to exploit the mounting desperation are violent extremist groups. If our mainstream parties do not change tack and refocus on the public’s urgent needs, we must fear for a future, fragmented Pakistan.