September 4, 2025

DHAKA – Once upon a time, budgeting was a conscious ritual. We carried cash, set limits before a trip or shopping spree, and carefully balanced our spending to ensure we did not exceed our means. Today, that discipline is quietly eroding—not because we earn more, but because we spend differently. The rise of digital payments has made money feel intangible and, with that, our sense of control has weakened.

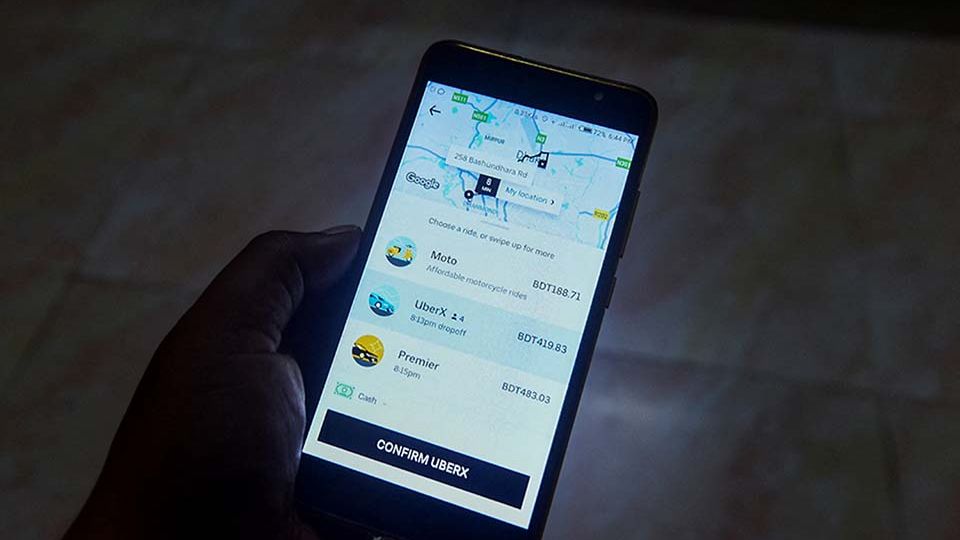

From mobile banking apps to cards and e-wallets, we now have effortless access to our funds anytime, anywhere. This ease has made impulsive spending part of everyday life. Dining out, spontaneous shopping, and quick weekend trips no longer require planning. The tap of a finger is enough. But this new convenience carries hidden consequences.

Nobel laureate Richard Thaler’s theory of mental accounting offers a useful lens that can help us understand our changing spending habits in the digital age. People tend to assign money to specific mental categories, such as “salary,” “bonus,” or “vacation fund,” and treat each category differently. While this can help organise finances, it often leads to irrational choices. For instance, a festival bonus may feel like “extra” money and be spent freely, even while the same person holds low-interest savings and racks up high-interest debt. These decisions become even more distorted when using digital money. Unlike cash, which we physically see and feel, e-payments reduce the “pain of paying,” making spending almost effortless. Without the physical cues of cash leaving our hands, we lose the awareness that once kept our budgets in check. As Thaler’s work in behavioural economics reveals, such biases can override rational decision-making, causing us to overspend and ultimately lose control of our financial well-being.

Another worrying trend is the demonstration effect. When we see others spending, we feel pressured to do the same. Whether it is friends dining out, colleagues going on expensive trips, or influencers flaunting their latest buys, we subconsciously follow. This social mimicry disrupts rational decision-making and leads to overspending, even among those who cannot really afford it. This irrational behaviour is further amplified by the use of digital money, as it removes the immediate concern of managing liquid cash, making spending feel effortless and less consequential.

But the implications go beyond personal finance. On a broader scale, these habits influence the economy itself. As e-money accelerates, the velocity of money—that is, how quickly money moves through the economy—increases. People are spending more frequently, pushing up demand. When demand outpaces supply, prices rise, ultimately contributing to inflation. This is not just theoretical; it is a real challenge facing many economies today.

Digital wallets, BNPL (Buy Now, Pay Later) schemes, and credit lines through apps further reinforce this illusion of affordability, pushing individuals deeper into unnecessary expenditure. We therefore need to find a way out. We must revisit the forgotten art of budgeting in this digital era, striking a delicate balance. We must decide for ourselves where digital money enhances our lives and where it silently harms them. For essential transactions such as bills, groceries, transport, and medical expenses, digital payments offer safety and convenience. But for leisure spending, such as shopping or eating out, it may help to switch to cash or at least pre-allocate a fixed digital spending limit. This creates a psychological boundary and reinstates some of the lost discipline.

Not all money should be equally accessible at all times. Setting personal rules such as “I will only use cash for dining” or “I will disable one-click purchases on weekends” can reintroduce mindfulness into our financial lives. Financial literacy is not just about knowing how to save or invest. In today’s digital age, it also means knowing when not to swipe, click, or tap. If we do not draw the line ourselves, technology will not do it for us. And while e-money may be invisible, its consequences, from broken personal budgets to rising national inflation, are very real.