June 10, 2025

SINGAPORE – Mannat Singh was only six days old when he was diagnosed with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID).

This means he was born without a functioning immune system, making him highly vulnerable to even the common flu. Without treatment, Mannat would not have made it past his first birthday.

His mother Harminder Kaur, 39, a nurse, recalled the guilt and fear she felt “because I made him this way”.

SCID is a rare life-threatening genetic disorder that affects one in 50,000 babies worldwide, with one new case born in Singapore every two years.

“It did not help our state of mind when his odds were stacked against him,” said her husband Harminder Singh, 39, an IT consultant.

It is also known as “bubble boy disease” after David Vetter, an American boy with the disease who captured the world’s attention for living all his life in a sterile plastic enclosure – his “bubble”.

At the time of his birth in 1971, a bone marrow transplant from an exact matched donor was the only cure for SCID, but there was no match available in David’s family.

In 1984, four months after receiving a bone marrow transfusion via a new technique, the 12-year-old died from lymphoma, a cancer later traced to a dormant Epstein-Barr virus in the donor bone marrow.

As for baby Mannat, he had Artemis SCID, a rare form of recessive radiosensitive SCID, which meant he could not be treated with radiation or have certain scans done.

Mannat Singh was born without a functioning immune system, making him highly vulnerable to even the common flu. PHOTO: THE STRAITS TIMES

Memories of what the couple went through with their younger son brought tears to Mr Singh, who said: “We were prepared to do whatever we could to give Mannat the best chance at life. We took a step at a time, discussing putting him on chemotherapy and deferring to the experts.”

Fortunately for Mannat, his condition was picked up at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH) through the National Expanded Newborn Screening (Nens) programme.

The programme, which started in 2006 with the aim of screening all babies born in Singapore for metabolic and heritable diseases, was expanded in 2019 to include five other treatable serious childhood-onset conditions such as SCID and cystic fibrosis.

In 2024, all newborns at KKH were screened under Nens, while the national screening rate in Singapore is 96 per cent. This involves pricking the baby’s heels to collect a blood sample between 24 and 72 hours after birth.

Screening for SCID involves checking the baby’s blood for DNA fragments called T-cell receptor excision circles (Trecs), which show that the immune system is making T-cells properly, said KKH geneticist Ting Teck Wah.

The test does not confirm an SCID diagnosis, but abnormalities such as low or absent Trecs signal that the baby needs to go through more testing, he said.

After screening almost 178,000 babies since 2019, Nens has picked up two babies positive for SCID, Dr Ting added.

CAPTION FOR VISUAL:

GRAPHICS: THE STRAITS TIMES GRAPHICS

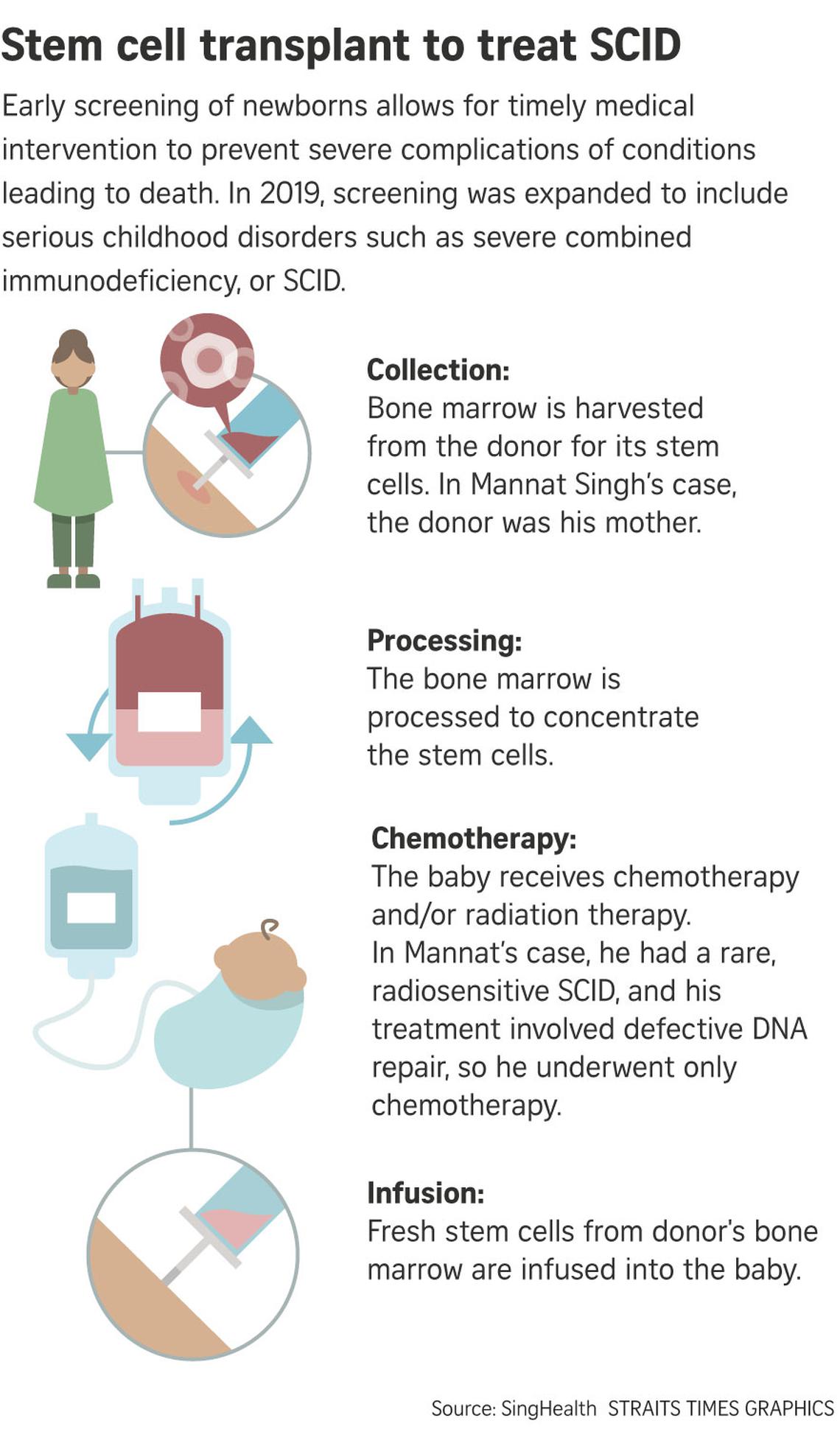

Dr Bianca Chan, a consultant with the rheumatology and immunology service at KKH, said the only real curative treatment for SCID is a bone marrow transplant from a healthy donor. Stem cells from the bone marrow of a healthy donor can develop into infection-fighting T-cells, helping babies with SCID build a functioning immune system.

“The highest success is when it is performed within the first three to four months of life, before the baby develops significant infections. This makes SCID screening at birth crucial for early diagnosis to actively prevent infection,” she said.

Dr Chan added that if the baby has an active infection before the transplant, its survival rate even with a transplant is only 50 per cent, “because it becomes very, very difficult to have a successful transplant”.

Mannat Singh and parents Harminder Kaur and Harminder Singh, with KKH doctors (back row, from left) Michaela Seng, Ting Teck Wah and Bianca Chan. PHOTO: THE STRAITS TIMES

Dr Michaela Seng, a senior consultant with the haematology and oncology service at the hospital, said a programme is immediately put in place to protect the child from infections before doctors prepare for donor selection.

“We meet the parents to explain the implications of the diagnosis and tell them they are typically appropriately suitable as potential donors. We also go through the process of harvesting and processing the donor stem cells, and the lab then receives these stem cells… and prepares small bags of what we call memory T-cells that help fight infection,” she said.

“During this time, the baby is admitted to the transplant unit and undergoes complete isolation. For seven days, he is given conditioning therapy, which is chemotherapy that is tailored to the size and the weight of the baby, to allow us to clear unnecessary cells that would prevent successful engraftment of the donor stem cells. The donor cells are then infused, and we wait for the transplant to take effect,” she added.

Mannat became the first newborn in Singapore to have his SCID diagnosed at birth, and the first to receive a stem cell transplant – from his mother’s bone marrow – before the symptoms emerged.

Today, at 19 months, Mannat is healthy and asserting himself with his parents and older brother Birakaal, aged four.

“I feel now that life has returned to normal and we have put the past behind us. We are now looking forward to having the boys grow up healthy and happy,” Ms Kaur said.