August 13, 2024

DHAKA – Bangladesh’s worsening economic crisis has spun off a price shock with food inflation crossing 14 percent in July for the first time in 13 years.

Part of the reason was a nationwide supply chain disruption caused by weeks of deadly protests that led to the fall of the Sheikh Hasina-led government.

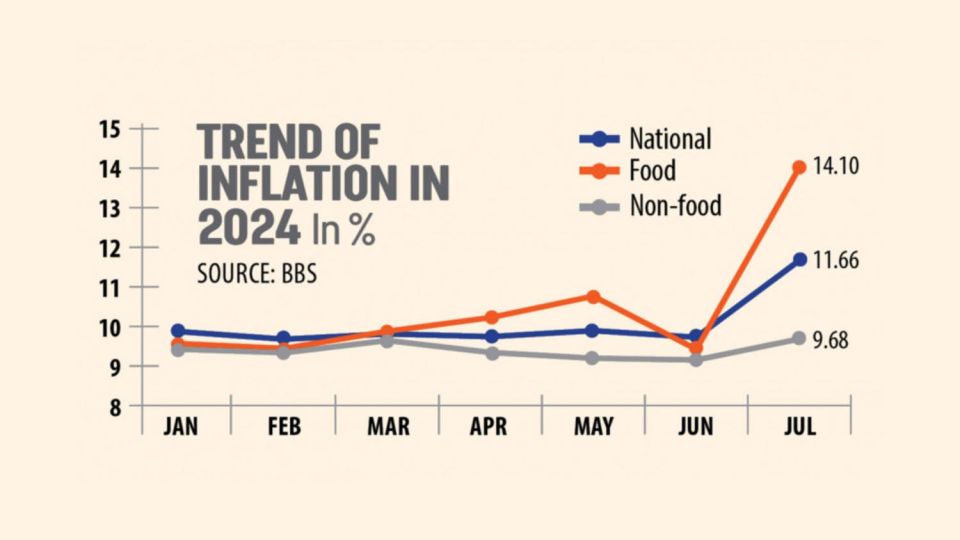

The consumer price index that includes food and non-food inflation rose 1.94 basis points to 11.66 percent in July from the previous month, according to data released by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics yesterday.

Moderate inflation is a fact of life, but higher inflation hurts fixed-income people badly. Consumers lose purchasing power faster at a higher rate of inflation. People are forced to chip away at precious savings.

“July was a month of turbulence and economic disruption. Supply chains broke down because of shutdowns, curfew, and internet blockage. These adversely affected the supply of goods in various markets,” said Zahid Hussain, a former lead economist of the World Bank’s Dhaka office.

The statistical agency published inflation data after Bangladesh formed an interim government following the end of Hasina’s 15-year regime. Hasina fled the country in the face of mass protests led by students.

Elevated consumer prices have a long life in Bangladesh. Since March 2023, the overall inflation has stayed over 9 percent.

While economists blamed the price surge in July on the supply chain breakdown, they also raised questions over the statistical agency’s past shoddy data that kept inflation relatively subdued. The actual data could be much higher. The economists have now urged the government to reveal the real inflation data as Hasina’s rule ended.

The price spike came largely from food inflation in both urban and rural markets. Non-food inflation also increased, albeit at a much slower pace than food inflation.

Hussain said the increased uncertainty due to political turmoil may have created a “precautionary demand” for essential items.

“It is natural for people to try to stock up when they are not sure about the functioning of markets and the availability of goods even if markets are open. This may have created additional pressure on prices.”

The “fearless disclosure of the truth” may be another reason for higher inflation, he said. “The BBS may have felt no inhibition in releasing the numbers without massaging under the changed political circumstances.”

Prof Selim Raihan, executive director of the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling, concurred with Hussain and accused Hasina’s government of manipulating inflation data.

“The statistical agency didn’t publish the real data and showed the ‘reduced value’ to give political advantages to the government,” Raihan said. “We raised the issue with the government as well.”

He also pointed to the supply chain disruption since mid-July when student protests turned deadly. As a result, the low- and fixed-income people were the first to take a hit from a sudden price spike.