January 2, 2025

DHAKA – As inflation greets Bangladeshis at breakfast time, even the humble paratha becomes a symbol of struggle. Once hearty and filling, it now arrives thinner and lighter — a daily reminder of the unending calculations between hunger and affordability.

Last year, a simple meal of three parathas and a plate of daal cost Tk 39. Today, this modest breakfast demands Tk 50, as spiralling prices threaten the most vulnerable — day labourers, marginal farmers and transport workers.

For Mofazzal Hossain, a 45-year-old rickshaw puller in Mirpur’s Duaripara area, breakfast used to mean rice, vegetables and an occasional slice of fish. Now, it’s a cup of tea and a single biscuit. His earnings have plummeted from Tk 500-Tk 600 a day to Tk 350-Tk 400. Feeding his family of six has become a painful arithmetic, where every meal is a trade-off. “I hardly remember the last time we ate meat,” he says quietly, staring at his hands.

Mofazzal’s plight mirrors that of many others across Dhaka and beyond. In Karwan Bazar, Sattar Mia, a 38-year-old day labourer, often begins his day with an empty stomach. Once earning Tk 600 daily, he now struggles to make Tk 400. The rising cost of basics has forced him to skip breakfast at times, pushing his first meal to late morning. “Sometimes I eat at eleven. Sometimes later,” he says with a rueful smile. “It hurts, but what can be done?”

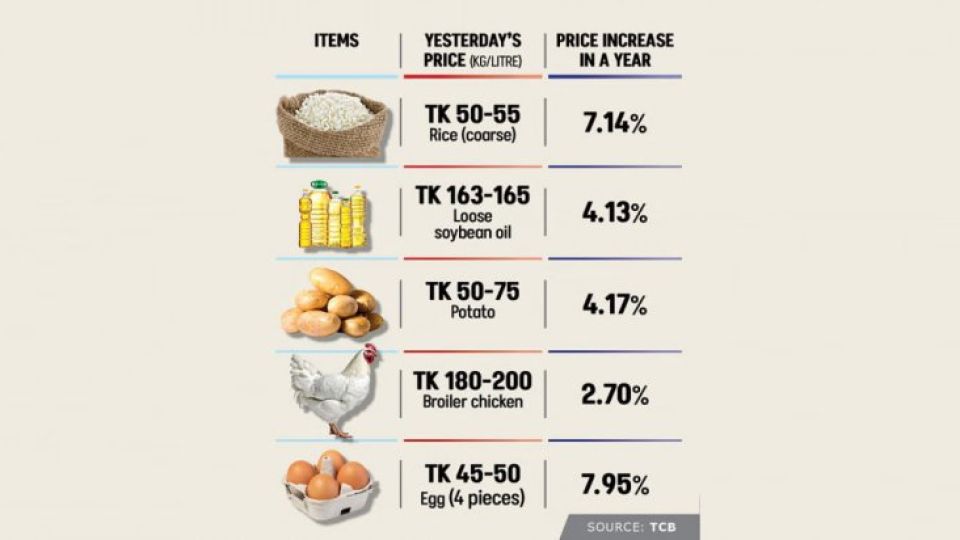

Food inflation soared to 14.1 percent in July, nearly doubling from January’s 7.76 percent, according to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. But behind the numbers lies human suffering. The statistics cannot capture the quiet sacrifices happening in homes like Sattar’s where sending money to the village is scarcely possible.

For Bangladesh’s working poor, each day begins with a painful negotiation as essentials like sugar and cooking oil climb ever higher in price: What can be sacrificed? What can still be afforded? For them, inflation is not just an economic phenomenon — it’s a test of survival. They sustain lives shaped by resilience and struggle.

In Barishal, grocery vendor Shambhu Nath Saha observes a shift in purchasing behaviour. Customers who once bought five litres of cooking oil now opt for one or two, and those purchasing two kilograms of sugar now settle for one. “Someone who used to spend Tk 2,000 on groceries is now spending Tk 1,000 or Tk 1,200,” he says.

Economists warn of serious implications. Fahmida Khatun, executive director of the Centre for Policy Dialogue, points out that lower food intake will affect nutritional and health conditions, with long-term consequences for children’s growth and education.

She further said the interim authorities have implemented several measures aimed at easing inflationary pressures. These include raising policy rates as part of monetary tightening, rationalising public expenditure by prioritising only critical development projects and removing tariffs on certain essential imports.

Fahmida, however, believes that winning the inflation battle hinges on improving the supply chain and increasing product availability in the market, a process that demands both time and sustained effort.

Price volatility had plagued neighbouring countries like India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan, which have managed to bring food inflation down to about 5 percent, according to media reports. Fahmida expressed optimism that Bangladesh could achieve similar results, though not without sustained effort.

“To address inflation in the current context, the focus must be on improving supply chains and increasing the availability of products in the market,” she said.

Fahmida also emphasised the importance of expanding open market sales of essential goods and broadening social safety net programmes to alleviate the burden on vulnerable populations. “These measures are crucial to mitigating the impact of rising prices on millions of households,” she said.

A study by the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies reveals a striking shift in dietary patterns in rural areas amid rising food costs. The daily average rice consumption per person climbed to 412 grams in 2023, up from 349 grams in 2022.

In stark contrast, the consumption of protein-rich foods like mutton and beef has plummeted. The study found that daily average consumption per person dropped to just 0.28 grams of mutton and 4.02 grams of beef, down sharply from 1.23 grams and 10.25 grams, respectively, the previous year. These changes reflect the difficult trade-offs many households make to cope with inflationary pressures.

Inflation remained persistently high in recent years under Sheikh Hasina’s government, a trend worsened by supply chain disruptions. These disruptions were fuelled by social and political unrest leading up to the August transition in the political regime, further intensifying the economic strain on households.

In Dhaka, fruit vendor Nur Islam Sheikh sees a similar trend. Apples that sold for Tk 180 per kg a year earlier now cost Tk 300, and customers who bought three kilograms now haggle for two.

Outside the capital, the situation is grimmer. Samiul Islam, a 40-year-old microbus driver in Dinajpur, earns a stagnant monthly income of Tk 15,000. Rising food prices have altered the family’s equation, forcing them to cut down on meals and essentials.

“Sometimes, I skip meals so that my children don’t go hungry,” Samiul says.

In Kushtia, Babul Kumar Acharjee, a battery-run auto-rickshaw driver, echoes this sentiment. His family now lives on rice, vegetables and daal, with meat a distant memory.

Mehedi Hasan, a welding mechanic in Shimulia, a village in Kushtia, struggles with frequent borrowing for daily needs. “Amid the struggle, I now have to ask for money from my relatives even for smaller needs,” he said.

Liton Ghosh, who runs a modest roadside eatery in Dhaka’s Tejturi Bazar, is a quiet reflection of how small businesses are adapting to rising costs. His words, like his meals, echo the struggles of the poor recalibrating to survive.

Liton recalls a time not so long ago when he could serve three parathas with vegetables for Tk 39. Today, the same plate costs Tk 50 — but with smaller portions. “The parathas are a bit smaller now, and the portion of vegetables has also been reduced.”

[Our Dinajpur Correspondent Kongkon Karmakar and Kushtia Correspondent Anis Mondol contributed to this report.]