February 28, 2022

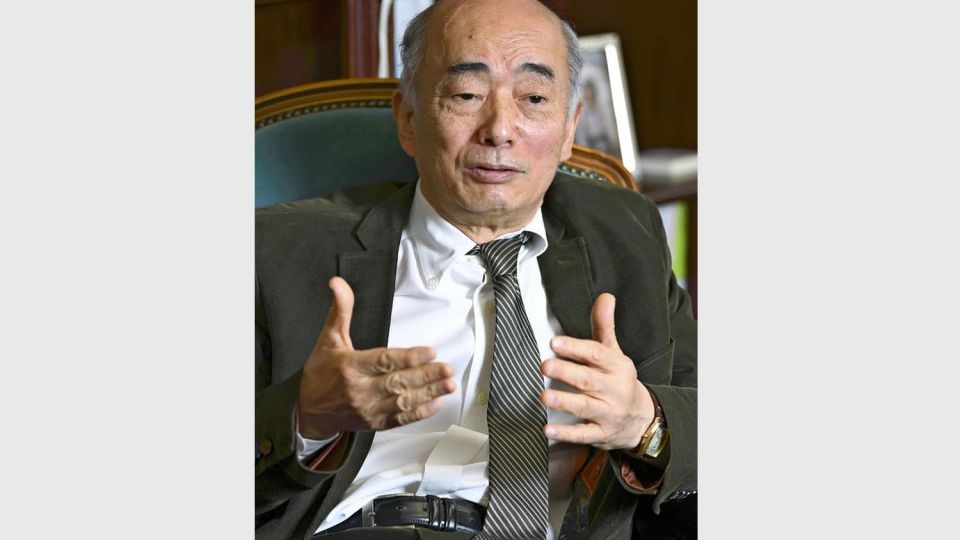

TOKYO – Japan’s diplomatic strategy is under scrutiny as the international order has been shaken by Western countries’ failure to stop the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The following was excerpted from remarks by Kenichiro Sasae, the president of the Japan Institute of International Affairs and a former Japanese ambassador to the United States, in a recent Yomiuri Shimbun interview.

The recent military action is highly risky, as it stems from the long-held hostility of Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has angrily complained many times that the problem is the eastward expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Even when Russia joined the Group of Seven advanced nations to form the G8, it was isolated because Moscow saw benefits in integrating with the West but could not give up its strategic interests. Behind this lies the Russian thinking that it has been hemmed in by Western and European society for centuries, as well as Putin’s view that Russia is being squeezed by NATO.

It is highly debatable whether [former Russian President Boris] Yeltsin or [former Soviet President Mikhail] Gorbachev would have acted the same way [in the same situation]. The latest invasion can be called a “Putin-style gamble.”

If the international community finds itself in a situation where it has to co-exist with Russian-held territory in Ukraine that was secured by military force, this will be a significant turning point, in the sense that it would weaken the prestige of the United States and embolden Russia and China.

The possibility cannot be ruled out that Russia will return to the diplomatic process if doubts arise in Russia, for example, that the country will dig itself into a hole if it goes too far. For the time being, it is important for the countries concerned to support Ukraine, continue to impose strict sanctions on Russia and keep channels open for dialogue, even if they are not official channels.

We should clarify our message so that Russia will not wrongly believe that G7 members cannot do much, and act quickly without taking a lot of time to decide on sanctions, as Russia is moving fast.

It is good that Japan came up with measures relatively quickly. From now on, as the leaders of Britain and Germany have declared, Japan should deal with issues based on the thinking that there are greater benefits at stake than economic ones. The crux of the matter is that Russia has directly challenged international law and order. For Japan’s security and strategic interests, it is best for Japan to clearly express that Russia’s actions cannot be tolerated, so that there is no effect on the ideology that Japan upholds and no effect on Asia-Pacific countries.

Otherwise, when a similar situation arises in East Asia and Japan has to seek cooperation from the West, the question will always arise, “What did Japan do in the Ukraine crisis?” When it comes to bilateral relations with Russia, Japan needs to consider issues and timelines and prioritize its major strategic interests rather than its immediate agenda.

Although the United States and Europe failed to stop the Russian attacks on Ukraine, they were correct in their strategy of pursuing diplomatic negotiations to the last minute. If they had used force against force, they would have given Russia an excuse to take advantage of that. The fact that the G7 and other countries concerned have united through good communications will be beneficial for future cooperation.

The withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan and the reinstatement of the Taliban may have given Russia the impression that the administration of U.S. President Joe Biden would not be able to take countermeasures if Russia adopted an aggressive stance, but this is not a direct reason [for the invasion of Ukraine]. Some say that Russia took the opportunity of the Beijing Winter Olympics having just finished, but for Russia, its long-held resentment over the Ukraine issue is now showing in its actions.

The United States says it will no longer be the “world’s police.” The American people don’t want that, and its political elites can’t take the initiative as they used to. Americans do not support their nation sending troops and paying a heavy price.

However, the United States will overcome that when the vital interests of its allies, including Japan, are at stake. I’m not worried about that. Rather, it should be an opportunity for Japan to reconsider the fact that it has been too dependent on the United States.

— The interview was conducted by Yomiuri Shimbun Senior Writer Toshiyuki Ito.

■ Kenichiro Sasae

President of the Japan Institute of International Affairs

After serving as vice foreign minister, Sasae was the ambassador to the United States from 2012 to 2018. He took up his current post in June 2018. He is 70 years old.Speech