January 6, 2025

SINGAPORE – Decades of development have turned Singapore from a lush island and fishing village into a thriving metropolis, although it lost much of its nature along the way.

But various research groups are now embarking on studies to coax wildlife back to Singapore’s urbanised land and coastal areas, through vertical greenery or underwater structures known as “fish houses”, which can provide a habitat for these animals.

Such work comes amid a global push for countries to halt the rapid decline of nature.

Under the Global Biodiversity Framework – an international treaty under the UN that aims to stop, even reverse, nature’s decline – countries have pledged to restore, maintain and enhance nature’s contributions to people by 2030.

The findings by researchers here could not only help to make urban Singapore a conducive home for both humans and animals, but also offer solutions for other areas grappling with the loss of biodiversity due to development.

Said NUS Associate Professor Peter Todd, who conceived the study on the fish houses: “As coastlines around the world are increasingly modified by urbanisation and the need to defend against sea level rise, it is vital that we find ways to mitigate some of the worst effects.”

Condos for fish

About 70 per cent of Singapore’s coastline is currently guarded by hard structures, including sea walls, which help to protect land and infrastructure from erosion caused by waves and tides.

This has resulted in the loss of fish habitats such as coral reefs and mangrove forests, said the researchers from the NUS’ Experimental Marine Ecology Laboratory, whose study was published in April 2024 in the Journal of Applied Ecology.

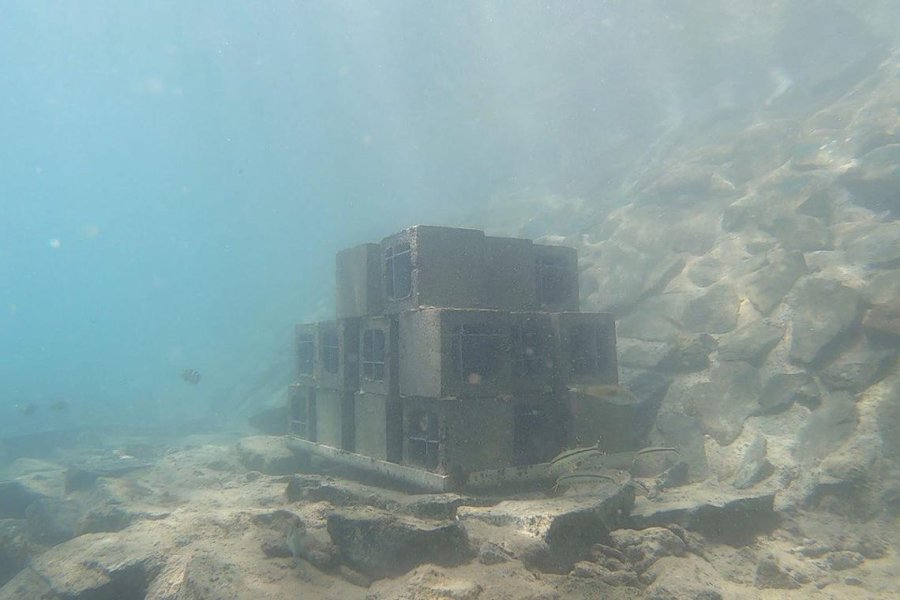

To encourage the return of fish life, the researchers in October 2019 deployed artificial structures made of concrete blocks, called fish houses, at the base of sea walls at five different sites at Pulau Hantu, one of Singapore’s southern islands.

“Sea walls and other concrete coastal infrastructure are usually designed in a very uniform way and are structurally very simple, but marine animals need places to hide, find shelter, rest and more,” said Dr Daisuke Taira, a research fellow at NUS involved in the study.

“Such grey infrastructure destroyed their habitats, so with the fish houses, we are trying to do something to mitigate the impacts for the fish to come back and utilise these habitats.”

Mother Nature is an unconventional architect, and natural ecosystems, such as coral reefs and mangroves, have a dizzying array of nooks and crannies for the animals that depend on them to hide in or find food.

Having a wider variety of sizes, shapes, types and arrangements of such features provide unique opportunities for different fishes to utilise these habitats. This is known among ecologists as “habitat complexity”.

In a coral reef, for example, hard corals and their different growth forms – some have branches, others look like plates, while others grow big and massive – provide a highly complex environment that can support fish, sea slugs, crustaceans and many other creatures.

Mangrove forests also have tangled webs of roots that provide little pockets of space for fish to rest or hide in.

Natural ecosystems such as coral reefs have an array of nooks and crannies for animals to hide or find food. PHOTO: CONTRIBUTED/THE STRAITS TIMES

But degraded habitats and man-made coastal defences typically lack the variety of features found in natural shores, said the researchers, who said that creating microhabitats is important to enhance biodiversity.

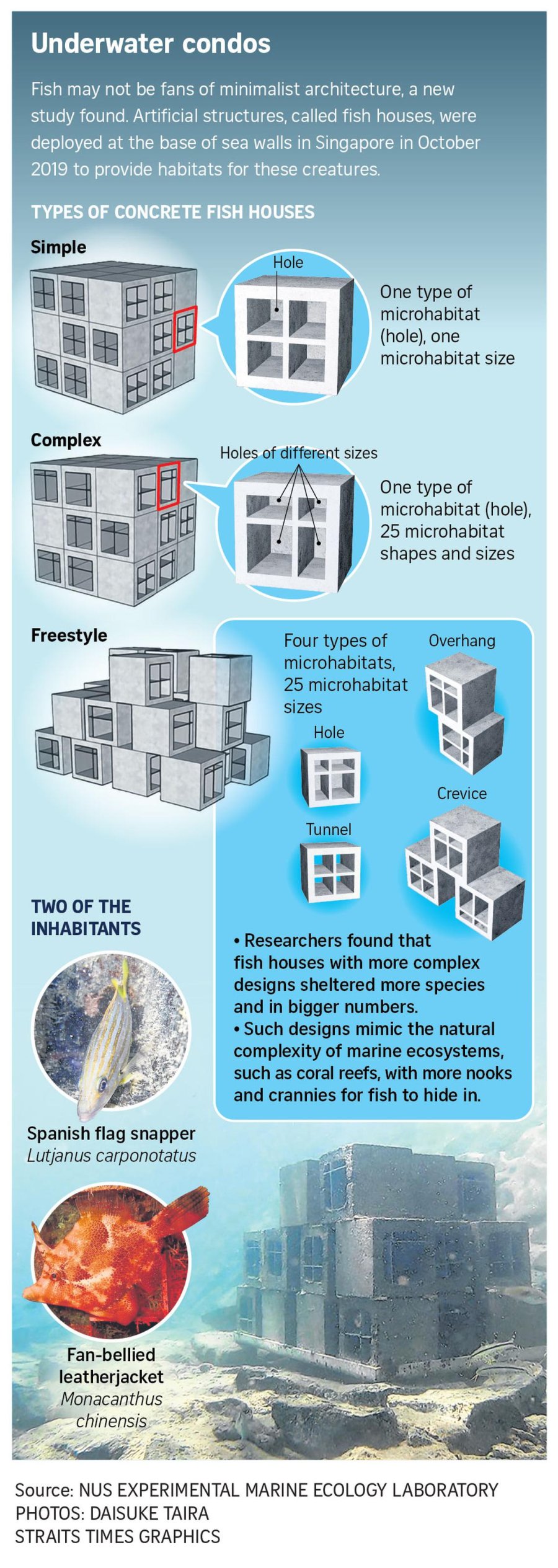

To investigate what types of artificial structures are most effective at attracting the return of fish life, the research team tested three different fish house designs of varying complexity – in terms of their shapes and the size of holes within each block.

The most simple fish house design involved 27 concrete blocks stacked up in the shape of a cube, and had 100 holes measuring 6.25cm by 6.25cm.

The more complex design was still cube-shaped, but had 100 holes of 25 different dimensions.

The most complex “freestyle” design was non-cuboid in nature, with the concrete blocks stacked in different shapes. It has holes of different dimensions and other habitat features to mimic little tunnels or crevices in a coral reef or rock. PHOTO: CONTRIBUTED/THE STRAITS TIMES

The most complex “freestyle” design was non-cuboid in nature, with the concrete blocks stacked in different shapes. It has holes of different dimensions and other habitat features to mimic little tunnels or crevices in a coral reef or rock.

All three designs were deployed at each of the five sites at Pulau Hantu, and were monitored with underwater cameras and through visual surveys.

The researchers found that of the three design types, the most complex fish house helped to accommodate greater fish diversity.

Study co-author Rachel Mark, who was an NUS undergraduate at the time of study, said the aim of the study was to find out what types of spaces fishes need, so they can be deployed to the sea wall area to attract fish diversity.

The researchers found that the two cube-shaped fish house designs attracted about 27 fish species, while the most complex freestyle fish house design drew in more species of fishes, and in greater numbers.

For example, the freestyle houses attracted more piscivorous fish, or fish that feed on other fish, such as the leopard coral grouper (Plectropomus leopardus). This could be due to the presence of microhabitats with large openings which could have attracted large fishes by providing them space to find food and ambush their prey, said the researchers.

Detritivorous fish, which refer to fish that feed on dead or decaying plants or animals, such as the blue-barred parrotfish (Scarus ghobban), were also found in higher numbers in the freestyle houses.

The most complex houses also attracted uniquely shaped fishes, including the elongated green wolf eel (Congrogadus subducens), deep-bodied copperband butterflyfish (Chelmon rostratus), and the vermiculated angelfish (Chaetodontoplus mesoleucus) – possibly due to the bigger holes in the structure, the researchers said.

The study also found that species like the silver demoiselle (Neopomacentrus anabatoides) use the houses throughout the day and night, which shows that structures like this can serve as permanent homes for these species. PHOTO: CONTRIBUTED/THE STRAITS TIMES

The study also showed that fishes use the fish houses for different reasons in the day and at night.

During the day, they typically enter the fish houses to find food and sometimes rest or ambush other fish. The time spent in the fish houses is also short – about a few seconds to 30 minutes, and they prefer spaces larger than them as they search for food.

At night, they primarily use it for resting, which largely explains why they spend a longer time in there and in smaller spaces with less visual exposure where they can snugly fit their body to avoid predators.

Dr Taira and Ms Mark said the findings showed that the effectiveness of fish houses depended on their design.

“This study provides more technical information on how fish houses deployed near sea walls can be designed to support higher fish diversity, which can be incorporated into future coastal defence construction,” said Dr Taira.

Green walls

Green walls can potentially help to mitigate rising temperatures and loss of biodiversity which are the results of climate change and urbanisation. PHOTO: CONTRIBUTED/THE STRAITS TIMES

On land, too, researchers are finding ways to improve biodiversity through the use of man-made vertical greenery systems, in which vegetation is incorporated into vertical surfaces such as walls.

Such green walls can potentially help to mitigate rising temperatures and loss of biodiversity, which are the results of climate change and urbanisation, noted a report published in November 2024 in the journal Building and Environment.

The study was a collaboration between Utrecht University in the Netherlands, Nanyang Technological University and bioSEA, a company that specialises in ecological design.

While the temperature regulation of green walls has been studied before, the biodiversity benefits these walls contribute are not well researched especially in tropical climates, said Utrecht University’s Katharina Hecht, the lead researcher involved in the study.

The study compares the green walls with their natural counterparts like natural cliffs, which Ms Hecht said is a novel approach to evaluate if building walls perform to their full potential in providing ecosystem services.

NTU’s Assistant Professor Perrine Hamel, who is also part of the study, said: “While there is mounting evidence for their efficacy to reduce surface temperatures and provide habitat, they are rarely monitored in Singapore, making it challenging for agencies to update their policies based on scientific evidence.”

The study measured surface temperatures of the vegetation on the green walls and natural cliffs, and that of the non-vegetated walls, as well as conducted animal biodiversity surveys to measure and compare the benefits of green walls.

A total of eight green walls on buildings – four climber and four foliage – four natural cliffs and eight non-vegetated building walls, were studied between August 2022 and March 2023.

Climber green walls consist of self-climbing plants that grow from the soil up on a structure, while foliage green walls typically consist of smaller plants that are potted in boxes and that are generally managed using an integrated irrigation system.

The green walls surveyed in the study include those at NUS and the F1 Pit Building, and the natural cliffs were found in Bukit Timah and Bukit Batok.

A total of 280 animal species were recorded across all 20 walls – foliage walls, climber walls and walls with no vegetation.

Of these, natural cliffs hosted the most number of species, with 115 recorded, including the Asian hermit spider.

Foliage green walls hosted 111, such as the yellow-vented bulbul, while climber green walls hosted 77 species, such as the pond wolf spider.

Walls without any vegetation had only about 20 to 39 species.

The researchers also found that animal diversity increases when there is more surrounding vegetation, such as trees within 10m of the wall, which can act as stepping stones for the animals to move from other nearby green spaces to the walls.

SOURCE: NUS EXPERIMENTAL MARINE ECOLOGY LABORATORY; PHOTO: CONTRIBUTED/THE STRAITS TIMES; GRAPHICS: THE STRAITS TIMES

The research also supported the findings of earlier studies that showed that green walls can act as temperature buffers for the building during the day and at night. They can help to cool the building in the day while providing insulation from cooler temperatures at night.

The results showed that green walls can help to lower the temperature around the building wall by an average of 0.6 to 0.7 deg C.

On the implications of the study, Dr Anuj Jain, director and principal ecologist at bioSEA and the study’s senior author, said he hopes that the collection of such data can be useful for decision-makers, such as building developers, to make more informed decisions in the built environment.

This can help to ensure regenerative – meaning having more nature than its original state – and multi-functional building designs that are conducive for wildlife.

On green walls, Dr Jain said: “Green walls cannot replace a natural cliff, they cannot replace a forest, but they are attracting a decent diversity of animals, particularly insects, where the details depend on the configuration and the complexity of the wall itself.

“That, itself, is already a very good starting point to incorporating biodiversity in urban environments.”

- Chin Hui Shan is a journalist covering the environment beat at The Straits Times.