October 3, 2024

MANILA – This weekend, several Catholic churches will be organizing blessings for pets to honor St. Francis of Assisi, the patron of animals and the environment.

I would push for a more ecumenical celebration called “Season of Creation,” involving Catholics and Protestants (see seasonofcreation.org) to get people to think more broadly about our interdependence, along the lines of the World Health Organization’s “One Health,” which emphasizes how human health interrelates with animal or veterinary health, environmental health and, only recently, plant health.

An expanded perspective means we have to educate ourselves about the relationships humans have with flora and fauna, and the planet. This can get very technical with the jargon around what’s broadly called “climate sciences,” focusing on the deterioration of the planet because of human negligence and abuse.

A more manageable, and effective, perspective is to think of our own lives at the individual, family, and community levels, and maybe too as a nation, and how those lives matter in the context of our interrelationships as spelled out in “One Health.”

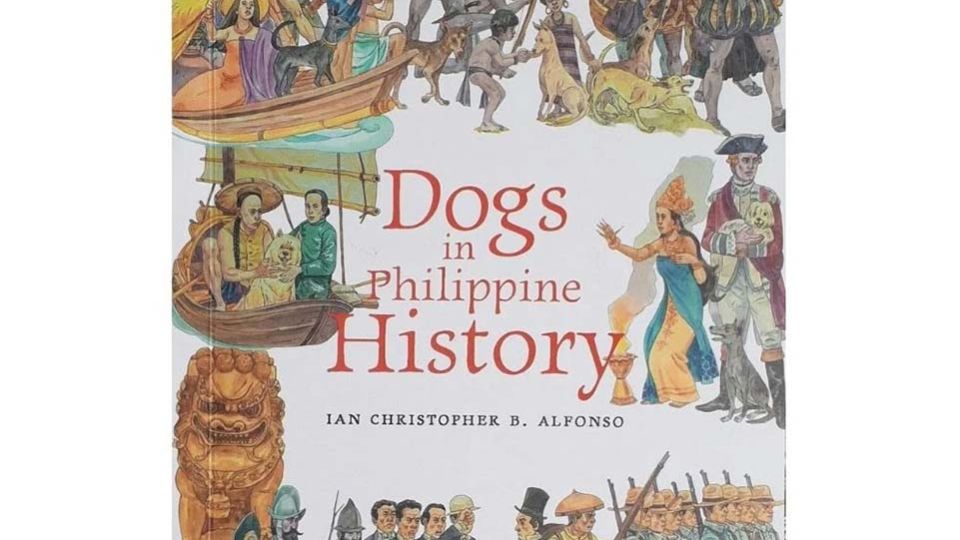

A good way of doing this at home, in school, and among friends, is to use the book “Dogs in Philippine History” by Ian Christopher B. Alfonso, a history faculty member at the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman. (Disclosure and bragging rights: he was also one of my best graduate students in a course on research methods.)

I’ve titled my column after Alfonso’s book which does not just discuss dogs through historical periods, usually divided into “precolonial,” “colonial” (Spanish and American), and contemporary times. You’ll find in the book a coverage of our dogs in the Philippines’ ancient past going back several thousands of years, and drawn from archaeological research.

Alfonso is one of those historians who was probably, in an earlier life or lives, a monk obsessed (in a good way) with minute details as they produced hand-illustrated and handwritten Bibles and books, not just about religion but also about philosophy and history.

Alfonso’s work with the National Historical Commission has brought him to different parts of the Philippines, each destination an opportunity to look into archives for references to dogs. The book overflows with photographs and illustrations. Dogs in masterpieces by Filipino artists, for example. The photographs are especially captivating, showing how dogs were considered members of the family and religious congregations. A few looked like photo-bombers, but most of them were certainly cherished as “kin.”

There is, too, a photograph of an American soldier shortly after the end of the Second War, with an “aspin” (“asong Pinoy,” a mongrel or street dog) resting by a river. How that soldier must have been longing for home, and perhaps a dog or dogs waiting for his return.

Alfonso is an interdisciplinary person, tapping into anthropology, archaeology, and linguistics. For example, the Spanish word “perrero” (perro”means dog) is defined in a Tagalog dictionary as someone who hunts dogs (mangangaso), as well as for someone who simply domesticates dogs (magalila ng aso), alila not so much a servant than someone deeply loved. (Admit it, many of us willingly describe ourselves as alila in relation to people we deeply love, and these days too, our dogs have turned us into their alila, forevermore.)

Alfonso has a regular-sized edition with 654 pages, and a lower priced, smaller but thicker “Puppy Edition” (868 pages, with additional material). There actually is so much more material that can be added: for example, a statue showing the human-dog bond found in the UP College of Veterinary Medicine, both in our animal hospital in Diliman, and in the main college in Los Baños. Alfonso has promised a volume 2, and I’ve pledged to help.

Alfonso’s book makes a good gift on St. Francis’ Day or the Season of Creation, and don’t forget, it’s already Christmas in the Philippines. It’s a good book, I assure you, and here’s proof: The first night I got the book, I was having my midnight snack, with my dogs. As I munched away, I thought my corioso cookies from Samar seemed a bit crunchier than usual but I was so engrossed in Alfonso’s books that I just went on and on, dipping into the cookie jar.

After a while though, I thought the cookies really tasted strange and I checked what exactly I was eating. Turned out that Alfonso’s book was so engrossing that I had interchanged two cookie jars, feeding the corioso to my dogs sitting by my side, and feeding myself with … dog biscuits.

That’s how good the book is. Get them from Shopee or from the Alfonso Yuchengco Museum bookshop (online orders accepted). Be careful though with what you eat as you read!