May 6, 2024

BEIJING – Jerry Lindenstraus is a 95-year-old Holocaust survivor who lives in an apartment in Manhattan’s Upper East Side in New York. People around him sometimes find it odd that the elderly Jewish man can speak a few Japanese words.Whenever the topic arises, Lindenstraus tells the story of how his family fled Germany and traveled to Shanghai in 1939 to escape the Holocaust.

Ellen Chaim, who later changed her name to Ellen Kracko, received this teddy bear when she was 2 years old. PHOTO: MINLU ZHANG/CHINA DAILY

After Japan fully occupied Shanghai, all schools in the city were obligated to teach Japanese, and the Shanghai Jewish Youth Association School where Lindenstraus was living was no exception.

In 1939, one month before the outbreak of World War II, the 10-year-old Lindenstraus arrived in Shanghai from Gumbinnen, a small German town in what was then East Prussia.

Stepping off the boat, the young boy was sweating profusely under the layers of his heavy German suits and shirts. More than 80 years later, he still remembers Shanghai’s brutally hot and humid summer.

Arriving with Lindenstraus were about 18,000 Jewish refugees who fled Nazi-occupied areas of Europe, settling in Shanghai from 1933 to 1941 to escape the Holocaust, as the Chinese city was among the few places that Jewish refugees were guaranteed acceptance in the early days of the war, according to the Shanghai Jewish Museum.

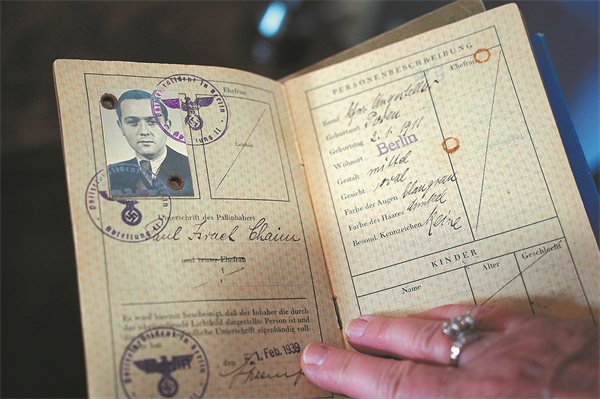

A passport belonging to Mr Chaim when his family left Nazi Germany and sought refuge in Shanghai in 1939. PHOTO: MINLU ZHANG/CHINA DAILY

Lindenstraus’ family did not realize it was time for them to leave until Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass, occurred in 1938 when Nazis burned synagogues, vandalized Jewish homes, schools and businesses, and murdered close to 100 Jews and sent thousands of Jewish men to concentration camps.

“The next day I went to school but it was no longer there,” Lindenstraus said.

However, the family had limited options. In July 1938, representatives from 32 countries attended the Evian Conference in France, and none agreed to accept a significant number of Jewish refugees, including the United States, the United Kingdom and France.

Only two destinations were available to the Jewish family — Shanghai or the island of Madagascar on the coast of Africa. They chose the former, an open city where no visa was required for entry.

The family of Ellen Chaim, who later in life changed her name to Ellen Kracko, had never considered leaving Berlin before Kristallnacht, a place where her family had been living for generations.

“We are Germans, my grandfather fought for the Germans during World War I,” Kracko said. “They considered themselves good German citizens. But then Kristallnacht happened and they realized that they could not stay there anymore.”

The Shanghai residence certificate of Jerry Lindenstraus. PHOTO: MINLU ZHANG/CHINA DAILY

In 1939, Kracko’s parents joined the more than 10,000 Jewish people who sought refuge in Shanghai before and after World War II.

Lindenstraus lived in Shanghai from the age of 10 to 17. He attended a Jewish school with about 600 students and 17 teachers. He learned English, chased girls, and even met his best friend, Gary Kirchner, who was from Berlin.

The boys joined the British Boy Scouts in Shanghai, which became an illegal group after Japan declared war on the UK and the US at the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941.

However, life in Shanghai was not easy. Sanitation was poor and health conditions such as diarrhea were rampant in the Jewish refugee community.

In the cold, humid winter, Lindenstraus’ father died of pneumonia four months after the family arrived in Shanghai because of a lack of antibiotics. Following the death of his father, Lindenstraus and his stepmother moved to Hongkew, now Hongkou district of Shanghai.

Kirchner’s living conditions were even worse than Lindenstraus’. While Lindenstraus’ stepmother was able to manage a small place to live, Kirchner and his parents lived in a big, barracks-like room that lacked privacy.

After the outbreak of the Pacific War, policies toward Jewish communities in Shanghai grew increasingly worse, leading up to the Meisinger Plan, an agenda to kill all Jewish refugees in Shanghai.

In 1941, the Nazis tried to convince the Japanese, who were their allies, to exterminate all Jewish refugees in Shanghai. Two years later, a compromise was reached with the establishment of a “Designated Area for Stateless Refugees”.

A ghetto in the neighborhood of Hongkew was built, where all Jewish refugees had to relocate and were strictly isolated by Japanese soldiers. Jews could only leave the area with special permission.

Ellen Kracko. PHOTO: MINLU ZHANG/CHINA DAILY

Recreating life

In the war-torn Hongkew district, Jewish refugees started establishing small businesses and set themselves up as doctors and teachers. People wanted to recreate what they were doing back home, Kracko said.

Gradually, a Jewish area inside Hongkew came to be known as “Little Vienna” for its European-style cafes, delicatessens, nightclubs, shops and bakeries. Kracko’s mother worked in a German bakery there.

Material conditions were austere in the Jewish ghetto. On Kracko’s first birthday, her grandfather baked a cake. She had no idea where he got the flour. The eggs and strawberry jam were from neighbors. The cake was taken to the bakery, where Kracko’s mom worked, to be baked.

Those memories were so deeply rooted in the family that many years after the war, when life had improved, Kracko’s aunt would still stop people from throwing out used tea bags and would steep them repeatedly to make tea until the bags were no longer useful.

Kracko, now 77, has short, light, blonde hair. She was wearing a pink shirt and silver earrings during an interview with China Daily in her house by the sea in Westchester County, New York.

She is quite familiar with modern technology and uses an iPhone well. During the day, Kracko’s phone was full of family messages. The great-grandmother was preparing for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, which was only a week away.

When asked about her place of birth, Kracko’s husband would often quip, “You’d never guess where she was born.”

Ellen would respond, “I was born in 1947 in Shanghai after World War II.”

People would then look wide-eyed and ask, “How?”

It has been estimated that around World War II, more than 400 Jewish babies were born in Shanghai and were called “Shanghai Babies”. Kracko is one of them.

Chinese, Japanese, Indians and other refugees from Germany and Austria lived in Hongkew. Shanghai at that time witnessed 1,000 monthly refugee arrivals, and Hongkew residents faced dire conditions since the start of the full-scale war in China in 1937, according to the Shanghai Jewish Museum.

In a less than 2.6-square-kilometer area, the ghetto was home to some 10,000 native Chinese residents living side by side with thousands of Jewish refugees, the museum said.

The Chaim family lived next to a Chinese family and Kracko’s mother would send cookies to the Chinese lady who lived downstairs. The Chinese lady, even though she could not communicate with them, would give her noodles in return.

Lindenstraus also had a Chinese family as neighbors in Hongkew. The Chinese family lived downstairs with their children and chickens, while Lindenstraus’ family lived upstairs.

They were friendly with each other, but they did not understand each other’s languages. Therefore, they communicated using pidgin English, a combination of English, German and Chinese words, Lindenstraus said.

“Believe it or not, the Chinese (who lived in Hongkew) were (treated) worse than we were,” he said. “The Japanese treated them terribly. The Chinese had to bow (when they saw the Japanese). We didn’t have to bow. But I’ve seen it. If the Chinese didn’t bow deep enough, boom, they were killed. It’s terrible.”

One school day, Lindenstraus’ class went to a public swimming pool outside the ghetto. It was a hot, muggy day, and he and Kirchner spent hours in the pool. When it was time to leave, the two boys did not hear the signal and were left behind, Lindenstraus said.

They were picked up by a Japanese army truck.

“We were very scared,” he said. When they finally arrived home, they found Lindenstraus’ stepmother was so worried that she blamed everything on Kirchner and his mother, and the two mothers had a big fight.

Sheltered in Shanghai, Lindenstraus, along with many other Jewish refugees, did not know what had happened in Europe and the Holocaust — in which 6 million Jews across Europe were murdered — until Japan surrendered in 1945.

The day the war ended — at first no one knew Japan had surrendered — Kracko’s mother remembered waking up early that morning and it was very quiet outside. She had never heard the street so quiet.

Then, she heard people crying in the distance. Then came the laughter. Kracko’s mother opened the door to find that all the Japanese stationed at the entrance of the ghetto had evacuated in the middle of the night — the war was over, she realized.

The Chaim family retained almost all evidence of their life in Shanghai, including a dog license issued by the Shanghai Municipal Council. The Jewish couple had a Pekingese when they were living in Shanghai.

In 1949, when the Chaim family was preparing to leave Shanghai and packing their luggage, their dog, not knowing what was happening, chased after their car as they drove away. The small dog, of course, could not catch up to the car and the Chaim family never saw it again.

After the war, Lindenstraus traveled to South America and the United States. Soon after settling in New York, he founded his own company. In his later years, Lindenstraus lived in an apartment three blocks away from his son’s family.

Jerry Lindenstraus. PHOTO: MINLU ZHANG/CHINA DAILY

Returning for first time

Some 33 years later, in the late 1970s, Lindenstraus returned to Shanghai for the first time with his son. Unlike the Shanghai he had seen when he was 17, there were no more rickshaws or beggars on the roads, yet people were still playing mahjong on the roadside.

When he returned to his boyhood residence, an old Chinese lady living next door came out and said, “Ah, I remember him.”

Lindenstraus’ son, who was a university student at that time, witnessed it all and shed tears at his father’s experience.

Lindenstraus’ boyhood friend Kirchner also went to the US after the war and settled in San Francisco. In their later years, the two old men visited each other and attended parties together.

Kirchner, who passed away recently, learned Chinese in San Francisco.

“That’s funny; not in Shanghai,” Lindenstraus said.

Lindenstraus said his stories often end with a sentence that he tells his grandchildren, “If it weren’t for Shanghai, I wouldn’t be here.”

The Chaim family lived in Shanghai for 10 years and then lived in Israel for about three years while waiting for the paperwork to go to the US.

In Israel, young Kracko still wore a qipao — the traditional Chinese dress for women — and some of the traditional Chinese outfits from Shanghai. She played in the Israeli desert and even witnessed snow there. If not for photos, she would have no memories of it all. Kracko’s earliest memories of life began in New York.

By the sea in her yard, Kracko stood beneath the setting sun, watching seabirds on the nearby island flying back and forth, and watching the tide rise and fall. In the fading sunlight, ships were sailing back into a New York port.

Kracko said she often stands there and wonders how a girl born in Shanghai ended up living here.

“I was a little girl, born in Shanghai, a place across the world. And now, I’m here,” she said.