February 7, 2023

MANILA – The past week has been somewhat encouraging for relatives of victims of Rodrigo Duterte’s violent anti-drug campaign as the International Criminal Court (ICC) decided to resume its investigation into the killings. But what’s next?

The ICC stressed that after a careful analysis of the materials provided to it, it was “not satisfied that the Philippines is undertaking relevant investigations that would warrant a deferral of the court’s investigations on the basis of the complementarity principle.”

Looking back, ICC suspended its investigation on Nov. 18, 2021 as a response to the government’s request for deferral, with the Philippine ambassador to the Netherlands saying that the Philippines has thorough investigations on the killings.

However, even if ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan said “the prosecution has temporarily suspended its investigative activities” while it assesses the Philippine government request, analysis of materials already collected will continue.

Then over a year later, the ICC, last Jan. 26, said the government’s efforts “do not amount to tangible, concrete and progressive investigative steps” that sufficiently mirror the ICC investigation.

Not an easy process

Lawyer Rodel Taton said the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP), as a result, “shall continue to conduct its investigations, such as to send missions composed of investigators, cooperation advisers, and if necessary, prosecutors, to the Philippines.”

Taton, dean of the Graduate School of Law of San Sebastian College-Recoletos, told INQUIRER.net that the ICC will “collect and examine different forms of evidence, and question a range of persons, from those being investigated to victims and witnesses.”

This won’t be easy, though.

“These undertakings rely on the assistance and cooperation of state parties, international and regional organizations, as well as civil society. The OTP gathers evidence in order to establish the truth about a given situation,” Taton said.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

While based on the ICC proceedings, the OTP already hurdled the first stage, where the ICC prosecutor determines whether opening an ICC investigation would serve the interests of justice and of the victims.

So with the latest decision of the ICC, Khan’s office will now seek evidence to identify who is the most responsible for the crime committed—crimes against humanity, as in the case of the Philippines.

When evidence is gathered and the “suspect” is identified, the OTP can request ICC judges to issue an arrest warrant or a summons to appear. The arrest warrant is issued if the suspect does not appear voluntarily.

But if the requirements are not met for initiating an investigation, or if the situation or crimes do not fall within the ICC’s jurisdiction, the prosecution cannot investigate, but may seek again the confirmation of charges by presenting new evidence.

‘Long and winding road’

Now, since the ICC heavily relies on the cooperation of member-states, lawyer Kristina Conti, assisting counsel for Rise Up for Life and for Rights, a group of relatives of the victims of Duterte’s anti-drug campaign, said the road to justice will be “long and winding.”

This, as the present and previous administrations already expressed that the Philippines will not cooperate with the ICC, with Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla saying that “they cannot come in here and impose themselves upon us.”

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

“I don’t get why they insist on entering the Philippines in spite of the fact that we’re no longer members […] I will not welcome them to the Philippines unless they make it clear that they will respect us in this regard,” he said.

It was in 2019 when Duterte, who was then president, then decided to withdraw the Philippines from the Rome Statute, which created the ICC to investigate the world’s worst crimes—genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crime of aggression.

As in the case of the Philippines, crimes against humanity are serious violations committed as part of a large-scale attack against any civilian population. This include murder, rape, imprisonment, enforced disappearances, sexual slavery and torture, among others.

But even if the Philippines withdrew from the statute, the Supreme Court (SC) decided in 2021 that the Philippines still has the obligation to cooperate in criminal proceedings of the ICC.

This, as Article 27 of the statute, which was cited by the SC, states that “withdrawing from the Rome Statute does not discharge a state party from the obligations it has incurred as a member.”

“It is not easy, as the ICC depends on the cooperation of the states. Remember that the Philippines already withdrew from the Rome Statute that created the ICC,” Taton stressed.

“Hearing the Department of Justice and some of the [possible] respondents in the investigation of the ICC speak about their reactions, it may indeed be quite difficult to bring them to ICC,” Taton said.

Victims not losing hope

But even if the Philippine government refused to cooperate, Conti, secretary general of the National Union of People’s Lawyers-National Capital Region, said materials can be provided by institutions outside of government because what they need to prove at this stage is who is the most responsible.

She said the ICC would have to trace who ordered the commission of the crimes against humanity, which are so “widespread and systematic.” So what proof should you need for that? “It’s the directive,” she told INQUIRER.net.

As stressed by Conti, “our argument is the statements of Duterte ordering the killings and giving absolution to anybody who, in the course of the operations, kills someone.” She said this was clear, stating that Duterte’s words were sweeping.

“These encouraged the killings,” she said. “Since the beginning, the remark that Manila Bay will turn red instigated, encouraged and sanctioned the killings of thousands of Filipinos, most of them poor.”

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Looking back, when former ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, who requested the ICC pre trial chamber to investigate the Philippine campaign against drugs, Duterte’s remarks found themselves being useful as evidence.

Bensouda said the words of Duterte and even other officials of the Philippines, “encouraging, supporting and, in certain instances, urging the public to kill suspected drug users and dealers” indicate a State policy to attack civilians.

Conti said “aside from the verbal instruction, a written instruction is also useful.” But while she acknowledged that it would be hard to find, there is a document that created the “subterfuge of a war”—the Command Memorandum Circular (CMC) No. 16-2016.

As she explained, the government can argue that the said CMC did not give instruction to kill, but it stated the need to “pursue the neutralization of illegal drug personalities as well as the backbone of illegal drugs network operating in the country.”

“Lastly, testimonial evidence. Usually, mostly in ICC trials, they have a witness who will testify on how it really works within the organization—it can be an eye witness, but it can be someone in the middle ranks.”

“Generally, it will be three-part. You have to prove the crime, you have to prove who committed the crime, and for that, you have to establish who instructed, who was instructed, and how the instruction was given,” she said.

Bloody war on the poor

Since the start of his presidency, Duterte was not known to hold anything back when the issue is about illegal drugs and even asked law enforcers to “shoot-to-kill” and assured he would “protect and take care of them.”

His violent campaign against drugs was highly opposed as it resulted in several rights violations, including the deaths of 6,249 individuals who were killed in over 200,000 police drug operations since 2016. The casualty figure, however, is official government data.

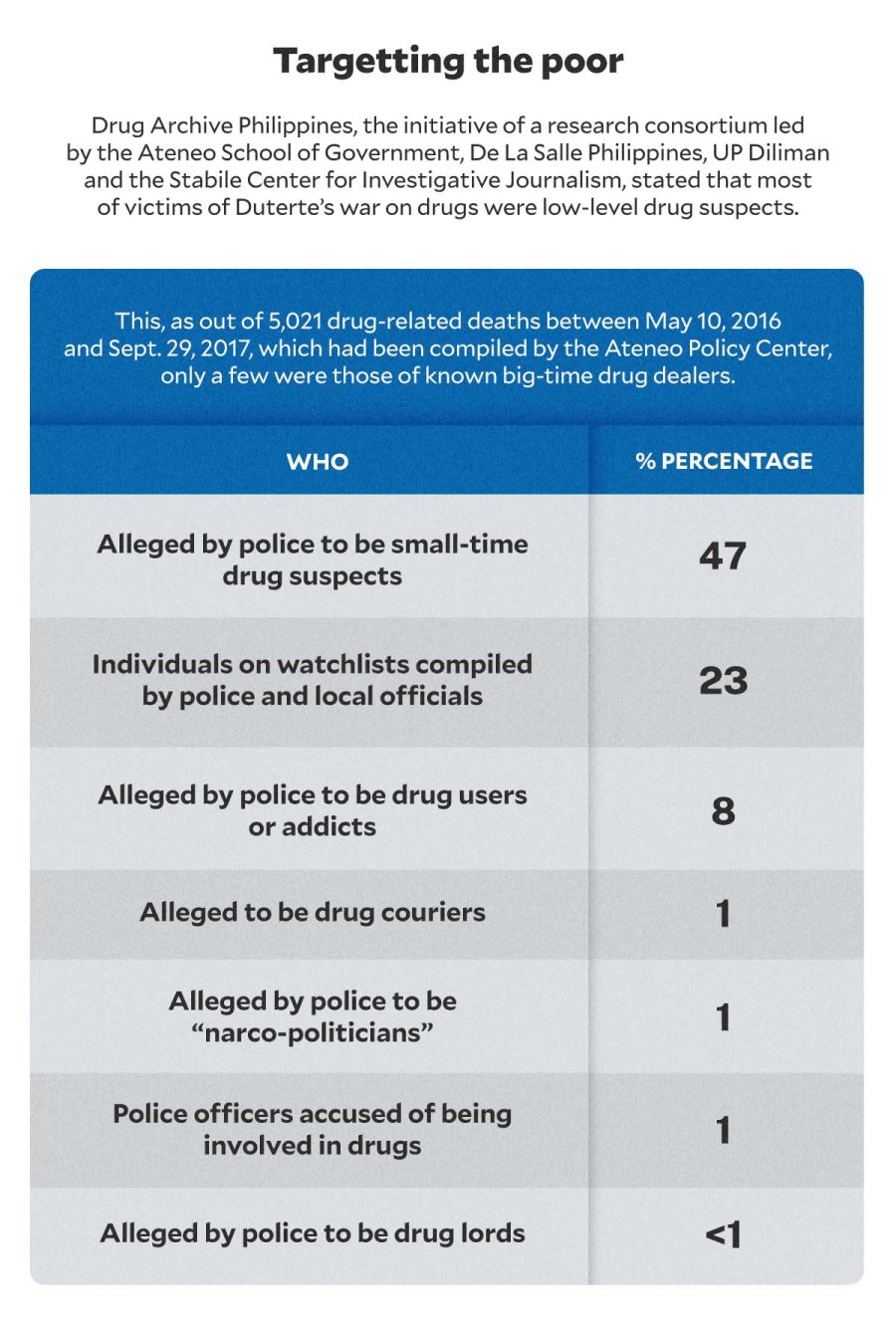

Based on data from Drug Archive Philippines, the initiative of a research consortium led by the Ateneo School of Government, De La Salle Philippines, UP Diliman and Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism, most of the victims were low-level drug suspects.

This, as out of the 5,021 drug-related deaths between May 10, 2016 and Sept. 29, 2017, which had been compiled by the Ateneo Policy Center, only a few of those killed were known big time drug dealers.

Some 47 percent were alleged by police to be small-time drug suspects, 23 percent were individuals on watchlists compiled by police and local officials, and 8 percent were alleged by police to be drug users or addicts.

The rest were those alleged to be drug couriers (1 percent), alleged by police to be “narco-politicians” (1 percent), police officers accused of being involved in drugs (1 percent), and alleged by police to be drug lords (less than 1 percent).

Many of the dead were killed at home (24 percent) or their bodies were found on streets or alleys (27 percent). Some nine percent were killed or found dead in a vehicle, based on data from Drug Archive Philippines.

As mirrored in surveys, the war on drugs of the previous administration enjoyed approval from most Filipinos, with some 54 percent “very satisfied” and 28 percent “somewhat satisfied” with the government’s campaign against illegal drugs.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

However, based on a survey by the Social Weather Stations (SWS) on Dec. 13 to 16, 2019, four in five Filipinos believed that there were a lot of rights violations committed such as extrajudicial killings.

The SWS said 76 percent of Filipinos believed there were “many” rights violations committed in the war on drugs—33 percent believed there were “very many” while 42 percent believed there were “somewhat many.”

It said 60 percent of Filipinos agreed that the rich were spared, while the poor were killed in the course of the bloody anti-drug campaign, which rights groups said has claimed the lives of as many as 30,000 individuals.

But defending his campaign, Duterte said drug lords use satellite phones and satellite imaging, which makes them really hard to track.

Likewise, he said the drug campaign was less aggressive against rich drug users because they get high on cocaine and heroin, which he said were not as destructive to a person as methamphetamine hydrochloride, or shabu.

He explained that these were less harmful compared to shabu, which he said could cause the brain to shrink after six months to one year of addiction, making it less likely for them to discern what is right and wrong.

Worst-case scenario

Taton said the Rome statute that created the ICC had foreseen the possibility of non-cooperation, especially when leaders of a state may be respondents in the cases before it.

“That is the reason why there are measures included in the procedures such as the continuance of the investigations, issuance of warrants of arrest or a summons should the matter be pursued by the prosecutor,” he said.

He said “the International community is not powerless, it can have individual actions or collective actions just to make a point for rule of law, justice and respect for human rights.”

But given the statements of officials, both from the present and previous administrations, expressing non-cooperation with the ICC, Conti said the worst case scenario is a possible suspension in the investigation and eventually, trial.

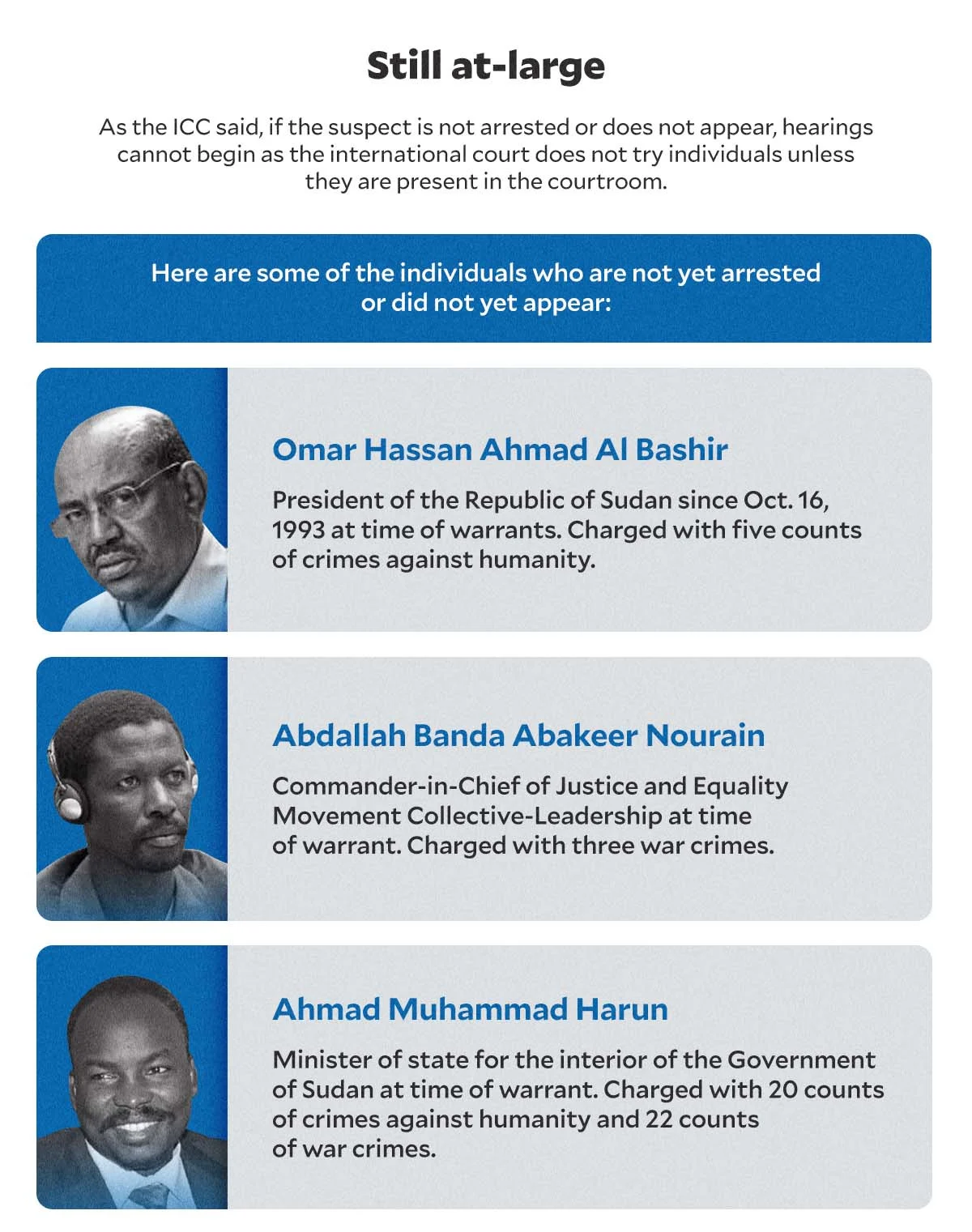

This, as she stressed that in the ICC, rules dictate that the suspect should be in custody because if the suspect is not arrested or does not appear, legal submission can be made, but hearings cannot begin.

Based on data from the ICC, there have so far been 31 cases before it, with some cases having more than one suspect, but while judges have already issued 38 arrest warrants, 14 people remain at large.

These included Abdallah Banda Abakeer Nourain, President of the Republic of Sudan since Oct. 16, 1993 at time of warrants and Ahmad Muhammad Harun, Minister of State for the Interior of the Government of Sudan at time of warrant.

Nourain is charged with five counts of crimes against humanity, while Harun was charged with 20 counts of crimes against humanity and 22 counts of war crimes, the ICC said on its website.

Hope lives where rule of law thrives

Conti said whoever will be identified as the most responsible for the alleged crimes against humanity in the Philippines could be safe from being arrested as long as he or she stays in the country, where the government already expressed non-cooperation.

However, “a lot of things can change,” Conti said, referring to the political climate that could change, especially every six years, when Filipinos elect a new president to lead the Philippines.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Likewise, she said arrests should be made only by member-states, but “they may also seek cooperation with the police or authorities of other non-member states.”

But Conti stressed that wherever the person of interest is, “you’re a person at-large, you’re a person with a warrant,” so “I wouldn’t call it assurance that he or she is safe if he or she stays in the Philippines because technically, this person will be a fugitive from justice.”

Since 2002, the ICC already issued 10 convictions, which include the cases of these individuals:

- Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, alleged member of Ansar Eddine, a movement associated with Al Qaeda

Found guilty as a co-perpetrator of the war crime consisting in intentionally directing attacks against religious and historic buildings in Timbuktu, Mali. Sentenced to nine years of imprisonment.

- Germain Katanga, alleged commander of the Force de Résistance Patriotique en Ituri

Found guilty as an accessory to 1 count of crime against humanity and 4 counts of war crimes committed in the attack on the village of Bogoro, Ituri in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Sentenced to 12 years of imprisonment.

- Thomas Lubanga Dylio, former president of the Union des Patriotes Congolais/Forces Patriotiques pour la Libération du Congo

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Found guilty of the war crimes of enlisting and conscripting children below the age of 15 years and using them to participate actively in hostilities. Sentenced to 14 years of imprisonment.

- Bosco Ntaganda, former Deputy Chief of Staff and commander of operations of the Forces Patriotiques pour la Libération du Congo

Found guilty of 18 counts of war crimes against humanity, which had been committed in Ituri, Democratic Republic of Congo. Sentenced to 30 years of imprisonment.

- Dominic Ongwen, Brigade Commander of the Sinia Brigade of the Lord’s Resistance Army

Found guilty of 61 crimes comprising crimes against humanity and war crimes, which had been committed in Northern Uganda. Sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment.

Given the statements of non-cooperation by government officials, Taton said “it should rather be a question of whether the rule of law should prevail than the declarations of certain officials of non-cooperation.”

“After all, we are still a people that values the rule of law. Otherwise, it proves that it is the r