August 30, 2023

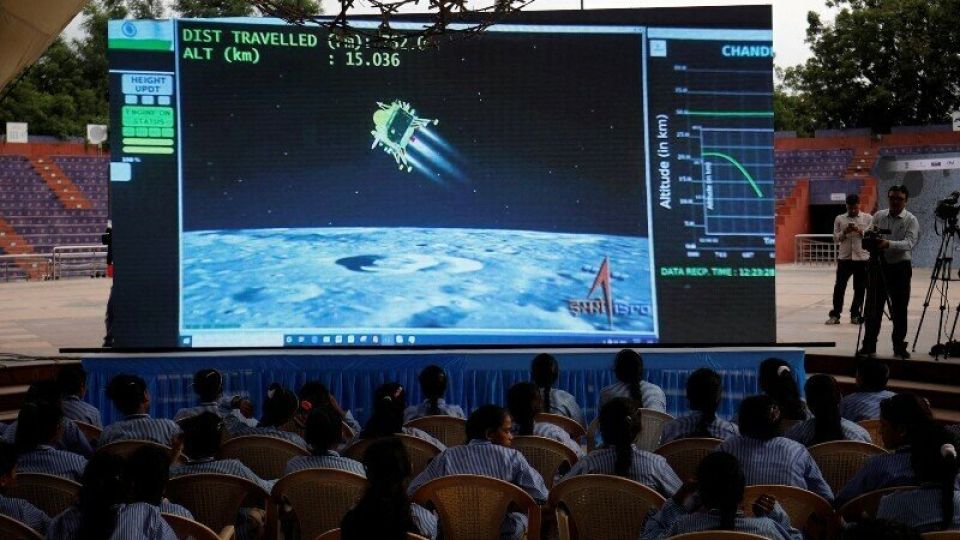

NEW DELHI – IT wasn’t entirely unexpected that zealous TV channels gave indiscriminate time and screen space to an awkwardly beaming Prime Minister Modi, rather than focusing exclusively on the crucial stage of Chandrayaan 3’s historic moon landing. The effort was to turn scientific success into a handy event with a narrow political intent.

It would, therefore, be of little value to the TV channels or to Mr Modi’s numerous chest-thumping cheerleaders to remember or to even want to know that the lunar journey they applauded lustily had its origins in a bruising battle between science and religious orthodoxy that began in Europe a few short centuries ago.

That battle has been going on in India, too, and appeared to have tilted in favour of science under Jawaharlal Nehru’s watch. A decade of gibberish spewing Hindutva, backed by Mr Modi’s anti-science fulminations, is beginning to unravel the early gains of inquiry Nehru sought to plant in India. But he didn’t anticipate anticipating the pitfalls ahead.

When Neil Armstrong walked on the moon in 1969, people in India were glued to the radio for a live account, but certain maulvis from their alcoves decried the event as fake as it clashed with their religious beliefs. Now, it is the turn of Hindu sadhus to proclaim the outstanding scientific success of Chandrayaan 3 as a miracle from India’s Vedic past.

The world knows that the space race, along with scientific research, has a military purpose.

It was through Alistair Cooke’s Letter from America, a riveting weekly dispatch for the BBC, that one got the news of Pope John Paul II “forgiving” Galileo in 1992, 400 years after the pioneer astronomer was hounded and abused for alleged heresy. The pardon was far from contrite, though. The pontiff merely declared that the ruling against Galileo had resulted from a “tragic mutual incomprehension”.

A little over 50 years before Galileo would find himself in papal trouble, fellow astronomer Copernicus of Poland had upended the Biblical belief that the earth was the centre of the universe, and the sun went around it. It is a tribute to this legend that some insightful leader named a popular road in Delhi after Copernicus.

Copernicus escaped religious censure by dying very soon after sharing his scientific insight, which he did by tracking the journey of the luminous planet Venus, visible to the naked eye. Galileo remained a pious Catholic, condemned to live longer and endure the invidious assault. The master’s experiments had established a principle of gravity earlier that would lead to Einstein formulating his theory of relativity. Galileo dropped objects of various weights and composition from Italy’s Leaning Tower of Pisa and found they were all affected equally by gravity, so they fell at the same rate.

The principle was naturally a key factor in the Chandrayaan project, as it has been with all space outings. Indian cosmonaut Rakesh Sharma’s landmark journey to space aboard the Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in April 1984 was one such journey. Yuri Gagarin and Neil Armstrong had preceded him (and each other) by years, but Sharma’s live chat from his spacecraft with Indira Gandhi is etched for posterity for its humility and joy sans rowdy nationalism.

Unalloyed fellowship from common citizens in India’s neighbourhood showed a similar humility last week. A friend from Karachi posted a picture of two flags on Facebook — of Pakistan, bearing the traditional crescent moon with a star, and India’s flag, planted firmly on the moon’s surface. She captioned it: “Moon on a flag, and a flag on the moon.” A generous spirit with charming self-criticism, it didn’t seem to get the reciprocity it deserved from Indian revellers. The world is giving India a standing ovation, and the president of the ruling party has been pouring vitriol on India’s space journey in earlier times. Mr Modi, he insisted, saw more space expeditions than all the previous outings put together.

A disturbing problem for science may lie in the all-round surge of artificial intelligence. Hollywood actors are protesting their roles being given to computer-generated characters. A priceless aspect of last week’s moon journey was the involvement of many women scientists in the project. What if AI started doing their research and planning space journeys?

The flip side of the possibility is equally sobering or worrying. Science, as opposed to scientific spirit, is a free-floating commodity. The clergy in Iran is supervising not only nuclear research, but fabricating drones for Russia. The heavily sanctioned North Korea is thumbing its nose at powerful adversaries with rockets and bombs it has been making and improving on. India may celebrate its scientists who built the bomb, its rockets and satellites. Pakistan ticks two of the three boxes, and it didn’t eventually have to be punished with the grassy cuisine Z.A. Bhutto had threatened to serve up in the endeavour.

Everyone has fabricated the toolkit from another toolkit, and mostly improved on it. The technology of cryogenic engines for the rockets that Russia gave India in 1993 was eventually critical to last week’s success story. Russia’s gift to India was vehemently opposed by the West, loudest of all by the US. It seems a bit odd, on the other hand, that an Indian submarine is acknowledged as Russian-built when it catches fire and drowns with precious lives lost.

Landing on the moon was indeed a laudable scientific feat for India. However, the world knows that the space race, along with scientific research, has a military purpose. And that’s where we need to turn to BRICS, with three nuclear powers, India, China and Russia, as its members. What about South Africa and Brazil? One dismantled its bombs and forsook building one again, and the other shut down its advanced bomb project in the interest of its democracy. Neither country betrays any disinterest in pursuit of the scientific spirit; the spirit that powered Galileo and his selfless colleagues to challenge blind faith with reason — a quantity under threat in India and Pakistan from their ruling elite.