November 3, 2022

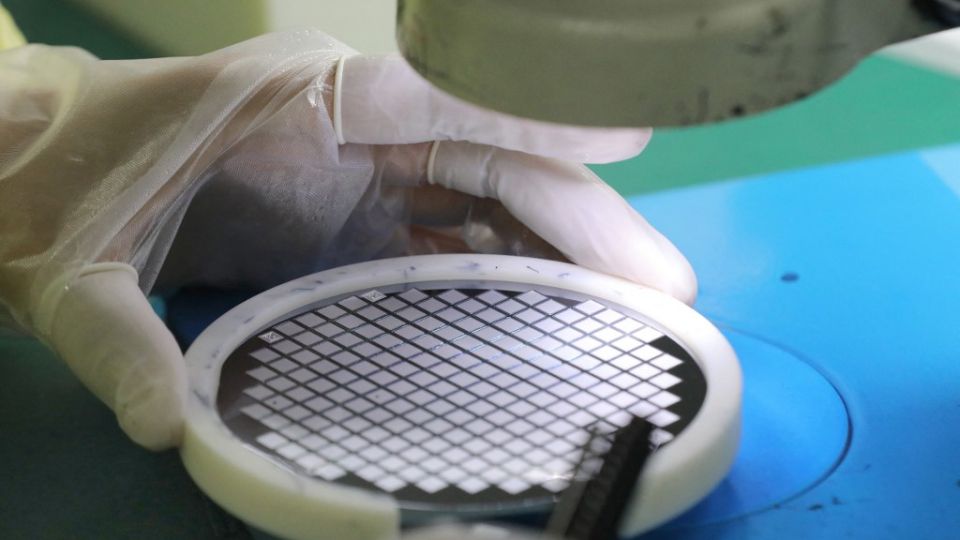

JAKARTA – As the government pushes for the establish of a semiconductor hub in the country, experts and foreign government officials have welcomed this ambition, given how the sector has turned into a fundamental building block of the modern world.

The United Kingdom’s Department for International Trade, UK Defence and Security Exports director Mark Goldsack told The Jakarta Post on Wednesday that deciding whether Indonesia should produce its own microchips was a game of finding balance.

“We all need an essential minimum, an irreducible minimum of stuff that we can control ourselves. […] ‘Do we need to make all the microchips necessary to sustain the car industry?’ No, we don’t. ‘Do we need enough to make the number of vehicles that are essential to the economy?’ Yes, we do,” he said.

Goldsack underlined that as a major car producer, it was logical for Indonesia to have semiconductor production onshore, at least to meet the minimum needs.

However, he pointed out that an extensive evaluation of the national supply chain was just as important because the option of trade and partnerships was always there to meet the balance. “We live in a global world, none of us can produce everything we need ourselves. So, the trick is to be very clear where you can’t accept risk, [and take] it out, and where you can accept risk,” said Goldsack.

“Everybody will always want to produce some and nobody can produce everything. So, you’re on a scale, and you [have to] work out where on that scale you sit and it’s going to be driven by what the rest of your economic needs are,” he added.

Indonesia’s Coordinating Economic Minister Airlangga Hartarto, speaking in public last week, invited the United States to invest in the archipelagic country’s semiconductor industry.

“I think we have to acknowledge that Indonesia is able to complement the supply chain from China. Indonesia has the market, the investment climate [and we] have strong comparative advantages, especially in steel production [and] the digital environment, including the raw materials for semiconductors,” said Airlangga on Oct. 25.

From a geopolitical perspective, Indonesia’s desire to attract semiconductor investment from the US is viewed as daring by experts, considering the country’s close ties to China.

The economic consequences notwithstanding, this course of action can be seen as good political balancing, according to Dafri Agussalim, an international relations expert from Gadjah Mada University (UGM).

“We can also say that this is Indonesia signaling to China how we have a strong bargaining position,” Dafri said, pinpointing how Indonesia is taking advantage of the ongoing “chip war” between the two superpowers by keeping both close.

Bank Permata chief economist Josua Pardede, meanwhile, agreed that this move was right to fill in gaps created by disruptions to the global supply chain as a consequence of looming trade wars.

“Investors must be thinking about moving their semiconductor production outside China in the hope of evading the impact of a trade war. Indonesia must take this opportunity by inviting US investors who are thinking about going out of the Chinese market,” said Josua.

He went on to say that, regardless of the potential windfall, the government should not forget that constructing a semiconductor hub was very capital intensive as it needed more advanced technology and had a relatively low spill over into Indonesian labor absorption, so the road ahead was long.

An expensive ambition

For his part, Jazi Eko Istiyanto, professor of electronics and instruments at UGM, confirmed that a semiconductor industry was an expensive investment due to its advanced and rapidly evolving technology that required regular upgrading.

Despite this, Jazi said it was not entirely impossible for Indonesia seeing as how India, a country he considered not far apart from Indonesia in terms of development, managed to have its own integrated circuit (IC) design fabrication plant (fab), which had released its own processor named Shakti.

Jazi explained that a fab-less option was more economically efficient, as US-based company Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) has done through subcontracting its IC fab to Taiwan’s Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) while it did all the designing. Yet this option, Jazi explained, was not without its own issues, such as a sudden glut or chip shortage as is currently happening, which reduces the market share.

However, Jazi said that the biggest obstacle to implementing a semiconductor industry in Indonesia would be talent in the sector.

“I see that lecturers and students have little to no interest in IC design. Generally, everyone is more interested in software [design] because it promises more [money],” said Jazi, explaining that human development in the sector was lagging and in need of government intervention.