March 29, 2023

BATU – As a fine drizzle fell over Indonesia’s apple-growing heartland, farmer Agus Ridwan inspected dozens of clusters of white and light-pink apple blossoms on the tree branches, and smiled brightly.

“They look okay today. I just hope the rain doesn’t get any heavier, or worse, turn stormy. That will surely ruin the flowers – and all my hard work,” the 47-year-old said.

Mr Agus, who has been growing apples for two decades on the volcanic slopes of Sumbergondo village in East Java province’s Batu city, has good reason to worry.

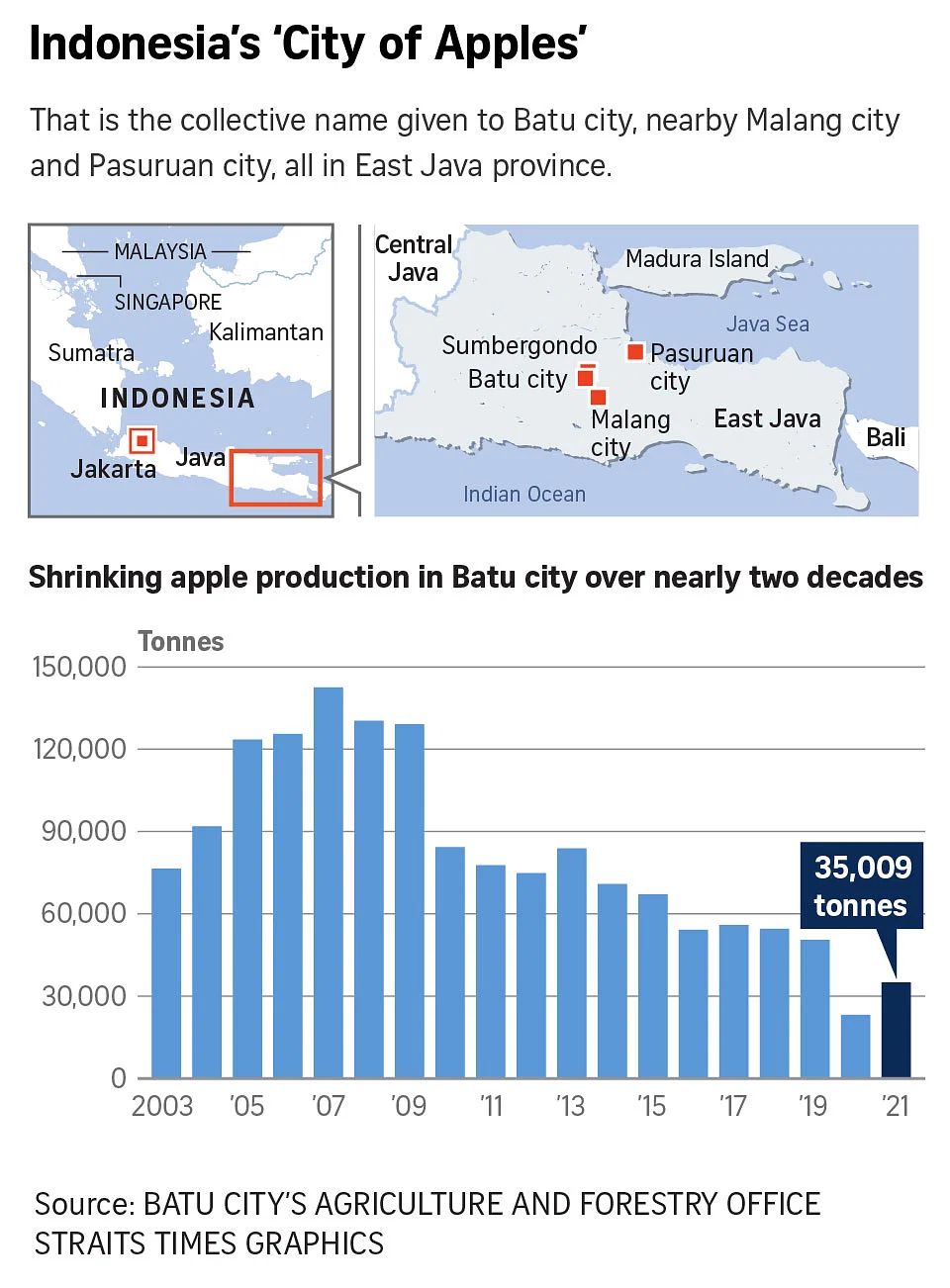

Apple harvests in Batu and neighbouring Pasuruan and Malang – known collectively as Indonesia’s “City of Apples” – have been poor for some years now, owing to climate change causing higher temperatures and rainfall.

This is compounded by ageing trees which are well over 30 years old, falling apple prices and less fertile soil. Other factors include deforestation and urban development.

Mr Agus’ 0.4ha orchard, about half the size of a football field, could previously yield up to five tonnes of apples per harvest, but in recent years, each harvest has yielded only 200kg to 500kg, he said.

Each kilogram can be sold for between 10,000 rupiah (about 90 Singapore cents) and 30,000 rupiah.

Unknown to many outside Indonesia, East Java is home to the country’s largest apple orchards.

Among the most popular varieties of apple from the region is the Manalagi – Indonesian for “where else” – which is green and small and, while not too juicy, is sweet and aromatic.

Sold in markets around Java, including the capital Jakarta, it can also be juiced, made into jams and dried into apple chips, among other products.

Apples are not native to the South-east Asian country, and are believed to have been first planted by the Dutch in the 1930s. They became commercially available in Indonesia in the 1960s and thrived for the next two decades in the subtropical highlands.

But apple production in the country has been suffering a steady decline.

Official figures show that in Batu, production of the fruit has fallen from more than 142,000 tonnes in 2007 to 23,000 tonnes in 2020, dealing a serious blow to farmers who have for generations depended on the crop to make a living and feed their families.

“In the past, we could get several months of a stable cool and dry season starting in May, which is a great time to grow apples.

“But the erratic weather now means it could be scorching one day and pouring heavily the next,” Mr Agus said, shaking his head.

“Look at the lower slopes – apple trees used to be everywhere. Many farmers have switched to growing oranges, carrots, tomatoes and other vegetables as well as flowers to supplement their incomes. I don’t know how much longer I can last,” he added.

Farmer Wawan Mujiono, 39, who has been growing apples for 12 years, said mornings used to be chilly, and he could work in his 1ha orchard until noon without feeling hot.

“It’s so hot these days, I have to wear a hat and look for shade by 10am. I’ve also been getting sunspots,” he said. “In the past, we could also get two harvests a year, but my crop has been failing the last four years.”

Climate change experts point to extended rainfall and soaring temperatures as a serious threat to apple farming.

The average temperature in the region has been rising, from 21 deg C between 2000 and 2010, to 22.5 deg C now, exceeding the ideal 22.2 deg C to cultivate apples, said Professor Rizaldi Boer, senior researcher at the Centre for Climate Risk and Opportunity Management at IPB University in Bogor, West Java.

Efforts to revitalise apple orchards, improve cultivation techniques and grow more climate-resistant apple varieties have been slow and inadequate, he noted.

“The government needs to support apple farmers, like it has done for oil palm farmers who could receive financial aid of as much as 30 million rupiah per hectare for rejuvenating oil palm trees, as well as assistance in getting superior seeds,” he said.

“But the aid scheme does not yet exist for horticultural commodities like apples.”

The Manalagi variety of apples is green and small and, while not too juicy, is sweet and aromatic. It can also be juiced, made into jams and dried into apple chips, among other products. ST PHOTO: ARLINA ARSHAD

While the Batu city administration provides seed assistance for apple rejuvenation, “the funds are very limited and far from adequate”, Prof Rizaldi noted.

Farmers have turned to potent synthetic fertilisers to improve soil quality and pesticides to deal with aphids, spider mites and fungus. With the high costs of these chemicals, some farmers have been forced to take out bank loans.

Farmers and experts fear worsening global warming may eventually wipe out orchards in Indonesia.

Professor Budi Haryanto, a climate change and environmental health researcher at the University of Indonesia, said: “If climate change is not controlled immediately and massively, further increases in temperature, rainfall, humidity and frequency of extreme weather will further damage the environment.”

“In fact, environmental damage will become more massive starting in 2050. So apple trees, which are sensitive to climate conditions, obviously face a threatening future.”

Mr Wawan said he would not encourage his children to be apple farmers, adding: “Climate change has destroyed us all. This job has no future, it ends with me.”