March 15, 2022

DHAKA – Fifty-six-year-old Babul Sardar of Debhata upazila in Satkhira was arrested with 50 bottles of phensedyl on December 11, 2021 by the Detective Branch (DB) of police. He was accused in four cases under the Narcotics Control Act, per the police claim. He was kept in the DB lock-up at the Police Lines for interrogation. Sometime in the dead of the night, he apparently committed suicide by hanging himself from the lock-up door’s iron rod with a nylon rope, which he had allegedly been wearing around his waist—a claim contested by his family. Babul’s family further alleged that he had been tortured to death in police custody. The on-duty assistant sub-inspector and constable were suspended—as a temporary measure—for negligence of duty.

This particular case raises some important questions. Why was an accused locked up for interrogation with a nylon rope around his waist? Shouldn’t there have been a safety protocol to remove any weapons and materials from an accused’s possession to eliminate the threat of self-harm or harm to others? What were the ASI and constable doing when the accused (allegedly) committed suicide?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star’s Google News channel.

Similar questions about police brutality in custody surfaced in the case of 34-year-old Raihan Ahmed, who was arrested in Sylhet in October 2020. Raihan was in good health when he was taken into custody, but soon fell ill there. When his condition worsened, he was taken to the Sylhet MAG Osmani Medical College Hospital for treatment, where he eventually died. The autopsy report revealed 111 marks of injuries on his body, and two of his nails had been pulled off. He had suffered severe internal bleeding due to injury.

As recently as in February 2022, a man named Wazir Mia died in Sunamganj district allegedly after suffering brutal torture in custody. He had been arrested, along with two others, on charges of stealing cattle. Wazir’s family claim that his arrest and torture had been orchestrated by the local police due to his feud with a union parishad member. Two probe bodies were formed to investigate his death. However, when this newspaper tried to contact the superintendent of police in the Sunamganj district, Mizanur Rahman, he said, “I don’t understand why this is such a big issue to report on for three consecutive days. The probe body is working and I cannot comment on it now.” The brusque reply only points to the apathy of police towards the people they are directly responsible for—those in their custody. Why is the evidence of brutal torture of a man in police custody not a big deal?

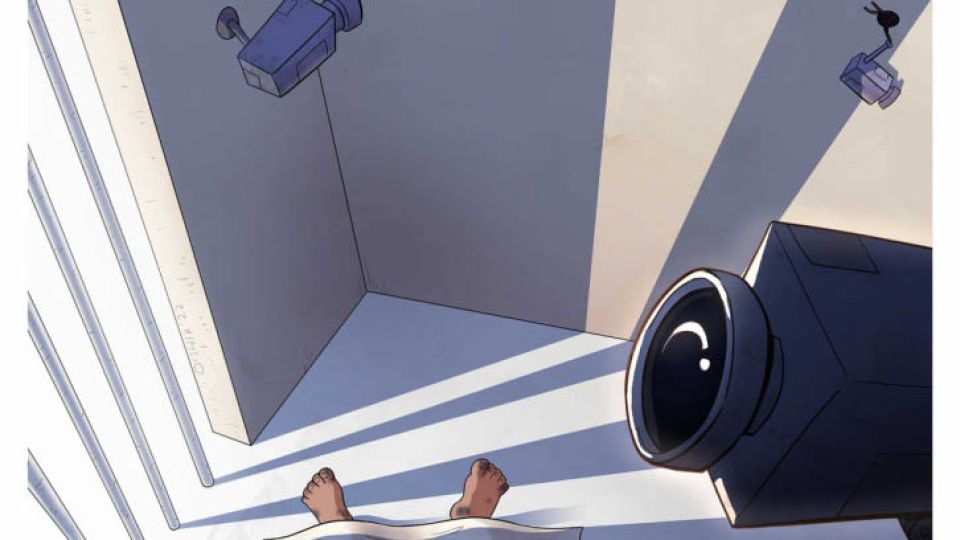

At times, the elements that could have been used as evidence are simply not available. Let’s take the example of 36-year-old tea stall owner Himanshu Roy of Lalmonirhat, who was picked up by Hatibandha police in January 2022 following the death of his wife, 30-year-old Sabitri Rani. After “questioning,” Himanshu was kept in the police station’s Women and Children Help Desk room. There, according to police, Himangshu took his own life by hanging himself from a window grill with a broadband cable. The CCTV cameras, which could have helped in investigating Himangshu’s “suicide,” were mysteriously out of order at the time. Also, the Help Desk room is just opposite to the OC’s room, yet no one noticed that a man was hanging himself from the window grill.

These incidents naturally take away people’s faith from the law enforcement agencies as the protectors of the people and upholders of law and order in the country. According to rights group Odhikar, between 2014 and 2019, at least 54 individuals were killed after the Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention) Act was enacted in 2013.

What is alarming is that, despite the enactment of the anti-torture law, which was passed as a part of the country’s commitment to the UN’s Committee Against Torture—Bangladesh is a signatory to it—the brutality of the police continues.

When the first-ever verdict in a case filed under the act was delivered back in September 2020, with the Dhaka Metropolitan Sessions Judge’s Court handing lifetime rigorous imprisonment to three police personnel over the custodial death of Ishtiaque Ahmed Jony, it gave people some hope that justice might finally prevail. The guilty cops were also asked to pay Tk 2 lakh each as compensation. However, the case is yet to be resolved in the higher courts, and Jony’s family is yet to receive complete justice.

Unfortunately, even though the Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention) Act was enacted in 2013, very few cases have been filed under the law since then as fear of retaliation makes most of the victims and their families shy away from filing complaints. And even if they gather enough courage to seek legal recourse, where would they go to file complaints? To the same police stations where they had been tortured? Often, the police themselves are not willing to take such complaints into cognisance. Those who do end up registering such cases have reported being threatened on multiple occasions.

Usually, internal investigative bodies are formed in the aftermath of custodial deaths, and the punishment is also mostly administrative, like suspensions. As a result, errant cops may think they can get away with any criminal act. This is the irony with law enforcement agencies—not just in Bangladesh, but in many other parts of the world: in the process of enforcing law, the enforcers often become delusional and think that they are above the criminal justice system. And perhaps their appetite for violence only keeps getting bigger. Former Teknaf police station OC Pradeep Kumar Das is an example of this. He was allowed to commit atrocities and harm the common people with impunity, and at one point, he turned into a monster who fed on the misery of the common people—perhaps just for the heck of it.

And often we come across media reports revealing police ill-treating the common people as well as, at times, even victims of various crimes. Traffic Sergeant Mohua Hajong herself had to go to great lengths to file a case with Banani police station against the driver of a vehicle—apparently the son of an influential person—after her father lost his leg as the car rammed into his motorcycle. Police initially refused to take the complaint into cognisance and tried to settle the matter through negotiation. The same police station, however, accepted a General Diary (GD) from the car driver against the victim, which suggested that 62-year-old Monoranjan Hajong—a former member of the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB)—was the culprit; his motorcycle was apparently coming from the wrong side. Later, in the face of protests demanding justice for Monoranjan, police had to take the complaint from Mohua Hajong. But she was “lucky,” because not everyone gets to have their voices heard.

These arbitrary and often unlawful activities by the police need to be thoroughly investigated by independent committees, involving human rights activists, civil society members and legal experts. And based on the findings of that investigation, the system—that gives law enforcers such impunity—should be reformed so that the police realise and learn to respect the gravity of their responsibilities. And if found guilty, the culprits should be treated like any other criminal and held accountable for their actions.

At the same time, our policymakers have to rethink the existing investigation framework for complaints against the law enforcement agencies, especially with regard to custodial torture and deaths, for the greater good of the common people. Also, the government should revisit policies related to the interrogation of suspects and accused, as well as the protocol related to how they are handled by the law enforcement personnel. There should be a holistic and detailed anti-torture policy framework to tackle this growing problem.

It is high time the government and the policymakers took a hard look at the misadventures of certain law enforcement agencies and officials, and held them accountable to the same laws that they are tasked to uphold. After all, law enforcers are not licensed to kill.