November 11, 2019

Government surveillance and deteriorating rights contribute to an imbalanced outlook in Asia.

The story Freedom House’s latest report tells about global internet freedom is grim. Of the 65 countries assessed in the report—which looked at events across the globe between June 2018 and May 2019—33 countries experienced deteriorating internet liberty. It’s the ninth year in a row that web freedom has declined.

Two major themes emerge in Freedom House’s 2019 findings in terms of the ways the internet is being used to undermine freedoms—first, as a tool to manipulate electoral processes, and second, as a tool to surveil, monitor and target populations. The report highlighted a handful of countries in the region where these trends are particularly noteworthy.

Electoral manipulation

On the topic of elections, the report finds that governments parties, or individual candidates employ three primary tactics.

First, is what the report deems “informational measures,” in which online discussions are manipulated in favor of governments or parties. Second is “technical measures,” in which access to news sources, communication tools, or in some cases the entire internet are restricted. And third is “legal measures,” which authorities apply to punish opposition parties, or activists as a way to crack down on political dissent.

When it comes to these three tactics the report has found that a few countries in the Asia Pacific region stand out as noteworthy abusers.

In Bangladesh, authorities used technical measures and legal measures to interfere in electoral processes. Authorities, for example, briefly blocked access to Skype after noticing that it was used as a communication tool by exiled opposition leaders and local activists. Likewise, mobile internet access was restricted across the country before and on election day in December of 2018. And, as a legal tactic, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government passed a new law criminalizing what it deemed online “propaganda” and then went on to use the law to arrest a news editor at a local outlet.

In India, leading political parties—the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party and the opposition Indian National Congress—both made use of informational measures in the form of bots and armies of die-hard volunteers to spread misinformation and propaganda on platforms like Whatsapp and Facebook. The BJP in particular made use of its own bespoke app, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “NaMo,” to flood millions of users with misleading and inflammatory content. The Freedom House report also noted that one researcher later revealed that the app was secretly routing users’ personal data to a behavioral analytics company with offices in the United States and India.

India also made use of legal measures to sway election results. Prior to the country’s national elections, for example, the police detained a journalist under the National Security Act for criticizing the BJP and Prime Minister Modi on Facebook.

In Thailand, authorities made use of legal measures in the form of restrictive and vague digital campaigning rules under which opposition politicians could be criminally charged for spreading “false information.” The report notes that one candidate for the opposition Pheu Thai Party even went so far as to self-censor and deactivate her Facebook account to avoid violating these rules.

In Cambodia the ruling party made use of technical measures to squash information access around election day in July 2018. On the evening before and the day of the country’s general elections, the Information Ministry ordered internet service providers to temporarily block over a dozen independent news outlets, including Radio Free Asia, Voice of America, and the Phnom Penh Post. Other, less critical outlets went unfettered.

In the Philippines, which the report credits with the dubious honor of having developed brand new disinformation tactics in its 2016 elections, candidates upped their manipulation strategies for the May 2019 polls. In 2019, political operatives spread information through closed groups on public platforms, where it’s easier to avoid content moderation. Candidates also paid social media personalities with small- to medium-sized followings to promote their campaigns on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, which makes disinformation campaigns seem more authentic, and also has the side benefit of costing less money.

States of surveillance

The 2019 report also notes that governments around the world are increasingly purchasing and building technology that gives them the ability to surveil monitor, and target individuals through their social media presence. The report notes, in particular, that a few of these countries have received assistance for this particular mission from the United States.

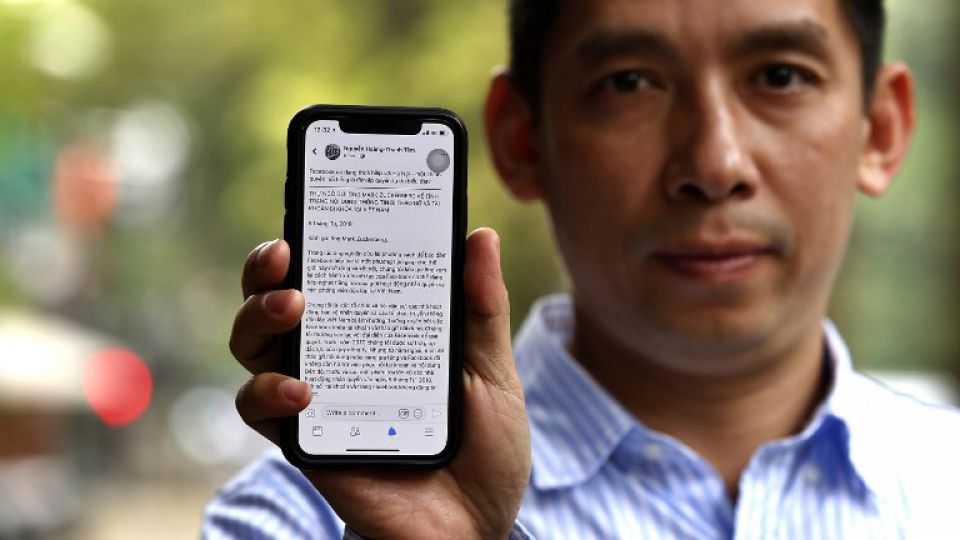

In Vietnam, the Communist Party government in October 2018 announced a new national surveillance unit equipped with technology to analyze, evaluate, and categorize millions of social media posts. Vietnam’s government has a long history of punishing nonviolent activists for content on social media. For example, the case of human rights activist and environmentalist Lê Đình Lượng,who was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison after a one-day trial for trying to overthrow the state, in part for Facebook posts criticizing the government.

In Pakistan in February 2019 the government announced a new social media monitoring program meant to combat extremism, hate speech, and anti-national content.

The Philippines and Bangladesh are two noteworthy examples of countries in the region whose social media surveillance strategies have been bolstered by the United States. In September 2018, the report notes, Philippine officials traveled to North Carolina for training by US Army personnel on developing a new social media monitoring unit. Relevant authorities have claimed the unit is intended to combat disinformation by violent extremist organizations, but the Philippine government’s history of labeling of critical journalists and users as terrorists suggest the unit’s mandate may not be limited cracking down on violent actors.

In April 2019, Bangladesh’s Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), which the report describes as being “infamous for human rights violations including extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and torture” was approved to travel to the United States in April 2019 to receive training on “Location Based Social Network Monitoring System Software.” This training occurred less than a year after Bangladeshi authorities led a violent crackdown on dissent during national protests and general elections.

China in a league of its own

When it comes to internet freedom, China deserves a category of its own. For the fourth year in a row, Freedom House has named China the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom.

The report details a new level of censorship across the country tied to the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre and widespread protests in Hong Kong. The report also details a new tactic used by the Chinese government, in which individual users are blocked from accessing WeChat, an app that has become critical to many aspects of daily life, including banking and transportation.

When it comes to electoral manipulation, this year saw China reach beyond its borders. China—along with Russia—was implicated in cyberattacks and information warfare linked to elections in democratic states. For example, the report cites a cyberattack launched in February 2019, against Australia’s Parliament’s computer networks, as well as the networks of three main political parties, three months before the country’s federal elections. That attack as been attributed to China’s Ministry of State Security.

Firms based in China have also become leaders in developing social media surveillance tools. The Chinese firm Semptian promotes its Aegis surveillance system as being capable of monitoring over 200 million individuals in China—a quarter of the country’s internet users.

American neglect

While the report highlights these threats to internet freedom around the globe, it doesn’t overlook the fact that these social media platforms that are so often exploited by antidemocratic forces are ultimately based in the United States, meaning some of the responsibility for their misuse is “a product of American neglect.”

The report calls on the United States to take the lead, through regulation, in making sure these platforms serve as forces for good, rather than forces for repression.