May 9, 2022

ISLAMABAD – Summer is around the corner. And, as always, the surge in electricity demand has sent our power system reeling. The centralised nature of the local electricity value chain has traditionally kept consumers reliant on the government to overcome chronic energy shortages. But this dependence is starting to unwind. The shift is in large part due to solar energy.

Within no time, solar energy has established itself as an inexpensive source of power generation and is well on its way to becoming a leading choice for households and industrial consumers. As technological advancements continue, higher solar energy penetration will have far-reaching implications for Pakistan’s power system.

It is incumbent upon relevant stakeholders in the public and private sectors to play a constructive role in this looming transformation in the country’s energy sector.

This is a revolution that has been a long time coming, and one that is not exclusive to Pakistan.

Solar energy has been at the centre of humanity’s civilisation journey.

It is argued that nearly 12,000 years ago, the rise in carbon dioxide (CO2) pushed the earth’s temperature upwards, leading to an abundance of plants and crops. These plants transformed solar energy into chemical energy. Plenty of food sprung up, upending the supremacy of hunter-gathering as our predecessors’ prime energy source.

This shift triggered a virtuous cycle, starting with a growing population that became denser over generations. With time, these groups became better at communicating and creating a repository of knowledge and technology, ultimately evolving into later years’ hamlets and towns.

The realisation about harvesting the sun’s energy is considered a defining moment in humankind’s shared history.

Our dependency and need for energy remain intact to date, although the sources continue to change. In fact, one can claim that our reliance on energy has reached an extraordinary level — various energy sources fuel today’s societies, and their shortage fetters our routine functions.

Fossil fuels have remained the dominant source of energy for the last few centuries. They helped accelerate economic growth, but at the cost of countless conflicts and ever-growing greenhouse gas emissions. While the former keep the world absorbed in a perpetual struggle to control the world’s energy resources, the latter pose an existential threat to our planet, in the form of human-induced climate change.

Notwithstanding this troubling backdrop, today’s world seems to embrace a new era of a solar energy revolution.

THE BEST OF SOLAR ENERGY GROWTH IS YET TO COME

Solar panels installed at a park in Peshawar | White Star

We have witnessed profound transformation catalysed by advancements in information technology. Given that one can experience that revolution with a swipe on their smartphones, it is most pronounced in our daily conversations.

A similar trend has been unfolding in the world of energy, although it is less glamorous and far from an everyday experience for many of us.

Supported by improving operational efficiency and plummeting costs, solar photovoltaics (PV) technology has experienced phenomenal growth over the last decade. It’s now a cost-efficient and fast-growing source of power generation globally.

Figure 1 represents the remarkable growth trend of the world’s solar power capacity. The world installed 129 gigawatts (GW) of solar capacity in 2020 — more than three times Pakistan’s total installed power generation capacity.

Figure 1: Solar PV capacity installations, 2005-2020 | Source: IRENA

According to Wood Mackenzie, a global energy research firm, annual solar capacity addition grew to 152GW in 2021 — 18 percent higher than in 2020 — despite the disruption inflicted by the Covid-19 pandemic. A transition towards clean energy sources will likely boost the demand for solar energy. Total solar PV installations are projected to be 2,236GW in 2030, averaging 232GW a year from 2022 to 2030.

Although this growth will happen across the globe, Asia will house the lion’s share, reinforced in principal by China, where annual solar PV installations will average 72GW throughout the 2020s — or 25 percent of the global demand. India will be another major market, with a total PV capacity growth of 130GW through 2030. These two markets will help the Asia region retain its pole position, by hosting 47 percent of the global solar PV fleet in 2030.

Despite being the fifth most populated country, Pakistan is not seen as a leading market for solar PV growth by global observers. Let us see to what extent those assessments hold ground, and if Pakistan could still position itself among global leaders in this context.

THE FIRST MOVER WHO CHOSE TO CRAWL

Pakistan was among the earliest lot of countries that conceived the potential of solar energy and devised a policy to exploit it. The targets set under the 2006 renewable energy (RE) policy demonstrate how favourably policymakers saw renewables, and they went the extra mile in offering unprecedented incentives to mobilise private capital into the sector.

What transpired in the following decade was an abysmal state of affairs on this front.

Some may argue that a lukewarm ambition to deploy solar energy in those years served Pakistan well, given how drastically the cost of PV technology has dropped. It is difficult to disregard that reasoning completely, but the favoured sources — namely oil and gas — of power generation did not stand the test of time.

Pakistan finally got its first large-scale PV project, the Quaid-e-Azam Solar Park, installed with 100MW of capacity in 2015. This was part of the generation capacity expansion plan launched by the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) government.

According to the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority’s (Nepra) State of Industry Report 2021, 530MW of large-scale PV capacity is connected to the grid. The Alternative Energy Development Board (AEDB) data shows that another 460MW is in the advanced development stage, slated for commissioning in the coming years.

As concerns about ‘excess power generation capacity’ have grown louder in the country’s power circles, developers engaged in this segment are likely to be given the cold shoulder by policymakers.

For small-scale, distributed solar PV capacity, 305MW is estimated to be connected as of December 2021. More than 90 percent of these installations took place between 2019 and 2021.

These numbers do not represent the actual state of affairs.

Industry sources reckon solar PV panel imports volume north of 1GW capacity in 2021 alone. Maryam Sarim, CEO of Instaenergy — a Pakistan solar energy company — underlines a “notable undocumented solar PV installation activity in the country.” She concurs that the scale of PV penetration is much larger than suggested by official stats.

There is a burgeoning distributed solar landscape, as households and businesses scramble to minimise their soaring electricity bills. There is no better alternative than putting up solar PV panels on their rooftops.

So what makes solar an attractive choice for electricity consumers? There is more than one factor that goes in its favour. Let’s review the most critical ones here.

SIMPLE TECH AND LOW COST FAVOUR SOLAR

Solar panels installed on the roof of a mosque in Mardan| Shahbaz Butt/White Star

First, let’s recognise the role of several stakeholders that enabled the distributed generation sector to take hold. The policymakers (AEDB) and the regulator (Nepra) laid the groundwork by introducing necessary framework conditions. The most notable perhaps is the issuance of the Nepra net-metering regulation in September 2015.

The regulator allowed electricity consumers to deploy RE technologies with an installed capacity of up to 1,000kW (1MW) — a usual residential connection has a capacity range of 3-7kW in Pakistan — and have a two-way flow of electricity.

This implied that a traditional electricity consumer would become a prosumer — a producer and a consumer of electric power.

Like any other policy, the net-metering regulation was only a necessary condition for the distributing generation uptake but not sufficient in its own right. There was yet the need for the demand and supply sides of the market to pull together in the same direction.

However, it was evident at the outset that these regulations would benefit solar energy, since other forms of renewables, such as wind and biomass, do not enjoy the same level of cost competitiveness and technological simplicity for installations with less than 1,000kW of installed capacity.

You won’t imagine people erecting wind turbines with the same height as Minar-i-Pakistan on their rooftops in the hundreds or thousands. Indeed, that would be a bit too many minarets.

On the other hand, PV technology has a clear advantage in terms of scalability. One can install a few panels to meet just the lighting needs of a small household or cover an entire rooftop to electrify even air conditioning appliances.

These advantages also position solar energy as a logical and compelling source of rural electrification in the country. The technology allows the development of isolated micro and mini-grids to serve dozens or hundreds of households in far-flung rural settlements. It is believed to have superior economic and technical value when compared with grid-supplied electricity in such cases.

Nonetheless, doubts about the attractiveness of solar energy remained widespread among consumers. Although many were convinced about the long-term prospects of their investment, the high up-front cost of solar systems deterred them from treading this path. Farman Lodhi, CEO of Solis Energy Solutions, says that, “the absence of financing solutions from local banks discouraged commercial and industrial (C&I) consumers.”

Another milestone was achieved in June 2016 when the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) revised its RE finance scheme of 2009, which had failed to pique public interest. The applicable interest rate was slashed from 12.5 percent to only six percent. For context, this was about half of what commercial banks demanded. Secondly, it recognised different consumer categories as per the industry’s needs.

Meanwhile, global PV manufacturers kept beating the most bullish cost reduction estimates, paving the way for a widespread diffusion of solar energy technology across the developing and developed world.

What did not exceed expectations domestically was our policymakers’ helplessness to arrest the swelling cost of electricity.

YOU NEED A REASON FOR NOT OPTING FOR SOLAR PV

As different pieces of the demand equation continued falling into place, the demand for solar energy grew exponentially. The time was ripe for a domestic industry to satisfy this demand across the residential and industrial segments. A wave of solar PV vendors mushroomed, resulting in about 200 firms that employ thousands of qualified professionals today.

According to the data compiled by the German Agency for Development Cooperation (Pakistan), about 18,000 distributed generators had net-metering licences as of December 2021. Of them, more than 15,000 were issued only in 2020 and 2021. These installations correspond to more than 305MW of solar PV capacity, which, as noted above, is considerably lower than the actual market activity.

Solar PV installed capacity with net metering

Figure 2: Distributed generation installation trends | Source: GIZ Pakistan

A research paper from the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) shows that residential consumers installed more than two-thirds of this capacity. Interestingly, net-metering installations have not had high penetration among commercial and industrial consumers (C&I) despite having excellent financial value for them. The country’s urban and high-income residential consumers lead the charge in terms of the geographical split of this capacity, concentrated in Lahore, followed by Karachi and Islamabad.

A brief analysis of the economics of solar energy explains this trend — and possibly what the future holds for Pakistan’s nascent solar industry. Figure 3 represents the range of applicable consumer tariffs for grid-supplied electricity and compares it to the estimated cost of solar power generation.

Generating solar power is a far better option on a cost of electricity basis. But the question remains: what do we do when the sun is not shining? In this case, the need for grid-supplied power is critical, if a solar system does not include batteries, which causes notable cost escalation.

A better metric is the payback period if the solar system is net metered. Since these systems often produce power that is more than a consumer’s consumption, the excess energy is sold to the grid. And when the sun is not shining in the evening, they can draw electricity from the grid.

The mechanism allows users to be net beneficiaries if they transmit more electricity to the grid than they draw from it. Maryam Sarim contends that “consumers can recover their entire investment within three to five years, depending on the average tariff and the capacity of the installed solar system.”

Figure 3: A comparison of reference consumer tariff and estimated solar energy cost range | Source: Disco tariffs and analyst’s own calculations

Although the C&I sector demand seems to have lagged behind residential consumers, it’s also true that tracking its growth is not easy in Pakistan. Installations above 1MW of capacity are not covered under the net-metering regulation, and they often operate on a standalone basis.

A case in point is a 10MW solar PV project permitted in 2019 for a foreign oil and gas exploration firm in the Sindh province. A host of C&I customers, representing a wide range of economic sectors, announced their plans for PV installations in the recent past. Not all local solar firms hold the technical, commercial and legal expertise required to serve this segment. However, a handful are fast emerging as strong contenders for future success stories.

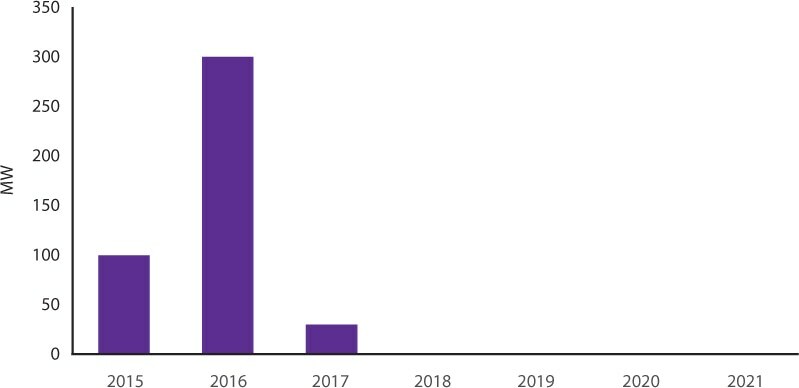

The utility-scale segment — that has an installed capacity range of five to 50MW and developed through a power purchase agreement with the federal government — has remained muted since 2018 (Figure 4). There are indications that some developers may bring a few hundred MWs of solar capacity online in the next couple of years. Yet, the prospects are far from the growth we expect to experience among households and C&I customers.

According to Nepra’s latest tariffs for new projects, solar PV is among the most effective sources of power generation. When power prices continued rising, Figure 5 shows the consistent reduction in solar PV and wind tariffs determined by the regulator.

But even in the face of all this encouraging evidence, the government has no structured plan for procurement within this segment.

Figure 4: Utility-scale solar installations in Pakistan, 2015-2021 | Source: Nepra

Figure 5: Nepra approved tariffs for new RE installations | Source: Nepra

WITH SUCCESS COMES CHALLENGES SO IS THE CASE WITH SOLAR ENERGY

Our local ‘success story’ does not merit global analysts’ attention, keeping most major players aloof from the developments we have experienced in the country. The size of the local solar market also remains negligible from a regional and global perspective.

We can attribute this to the absence of a concerted effort by the government to promote solar PV. This inaction keeps the market from growing to its optimal potential. In addition, the rapid growth of the solar market amid a lacklustre approach by relevant state institutions has given rise to a host of challenges.

The surge in distributed solar installations, serving primarily households, is a case worth mentioning. The sector has serious quality issues, perpetuated by the limited supply of a qualified workforce. Here, the demand has outstripped the supply of engineers. Maryam Sarim of Instaenergy notes her “troubles finding qualified PV installation technicians.”

Furthermore, interviews with industry sources reveal a concerning situation regarding the presence of unauthorised companies executing solar PV projects. Estimated to be above 400, these companies are more than twice the number of firms certified by the AEDB. The situation becomes more alarming with the widespread penetration of counterfeit and substandard equipment, raising concerns about the security of the electric infrastructure.

The IPS detailed a list of shortcomings in a recent survey after assessing 40 solar PV installations in Islamabad, Lahore and Rawalpindi. Notably, these systems were erected by certified firms, meant to comply with the specified standards and regulations. The research defined a comprehensive set of parameters as in a quality assurance audit, ranging from the quality of PV panels to the installation procedures and regulatory compliance.

According to Muhammad Hamza Naeem, a co-author of the study and a researcher at IPS, it is worrying that “22% of the [selected] solar systems are equipped with [PV] panels that don’t comply with the set quality parameters.”

The distribution companies (Disco) are playing an objectionable role in this segment. Their local officials demand ‘speed money’, essentially bribes. These payments are necessary for households to replace their existing electricity meters with new ones capable of gauging the two-way flow of electricity. If a consumer resists obliging, their net-metering applications are delayed, without any indication if they would ever get the meters installed.

Finally, Discos have yet to come up with a post-installation mechanism to ensure the security of the distribution infrastructure. It is counterintuitive to imagine that such standards would be enforced, even if they existed, since ‘speed money’ can also do the trick here.

The C&I segment is less prone to those quality issues, mainly because the installers have a qualified workforce, and their target group often has in-house engineers to enforce quality standards. However, the segment faces certain regulatory and financial challenges.

Firstly, the regulator has moved sluggishly on allowing industrial consumers to sign bilateral agreements with suppliers, known as ‘wheeling’. Banks prefer SBP’s scheme, where their risk is largely mitigated and returns are guaranteed. Many lack sector-specific expertise and willingness to evaluate and finance large-scale installations which don’t bear government guarantees.

The SBP scheme expires in June 2022 and will be up for review. The recent hike in the policy rate by 250 basis points (bps) has brought the benchmark rate to 12.25 percent. It is challenging to predict whether the state bank will continue the scheme. However, its discontinuation will prove a setback for the nascent PV market.

Farman Lodhi adds, “the discontinuation of the SBP refinance scheme might impede the current demand growth trend but will not impact it beyond a short period, keeping in view the ever-increasing grid electricity and fuel prices.”

Suppose the central bank retains the scheme but raises the applicable interest rate by 1-2 percentage points. In that case, it may not have a significant impact on the market’s growth momentum. It became evident when the federal government tried to milk the sector by imposing a 17 percent sales tax earlier in early 2022. Although the announcement created uncertainty in the market due to its administrative mishandling, it has not hurt the demand to the extent many feared initially.

SOLAR IS HERE TO STAY — AND GROW

Nobody has a crystal ball to predict the exact size of Pakistan’s PV market through the next few years. At the same time, there is no reason to disregard the widespread belief that PV installations will enjoy a steep growth trajectory.

It then depends on our policymakers whether they would prefer acting as mere bystanders and witness PV tech evolve into the first choice of electricity consumers. Alternatively, and more potently, they could play a proactive role in harnessing the untapped potential of solar energy in the country.

The second approach should follow a carefully crafted strategy to designate the solar industry as a strategically important sector of the economy — as done in many advanced economies — and a most preferred form of RE, along with wind energy.

Such a plan would identify and target challenges faced across the solar value chain, ranging from equipment manufacturers to electricity consumers. It would also aim to create a local supply chain and position Pakistan among the leading solar PV markets, to maximise the desired economic value. A sustained, sizable volume of PV demand is quite critical for such ambitions to be realised.

Some parts of the supply chain are easy to localise. In contrast, others, such as PV panels, have technical nuances that need time and effort to overcome. And that may not be great news since “more than half of the cost of a solar system [excluding batteries] comprises PV panels,” notes Maryam Sarim.

Given the enormous scale of Chinese firms’ production capacity, it’d be a long shot to suggest that our local production would be able to compete with those global giants on a commercial basis. But there are avenues of technology transfer and joint ventures to spur a local value chain under the umbrella of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

It will be regrettable should the government fail to play its desired role. Such inaction will limit the country from exploiting the vast economic potential of solar energy and PV technology. Admittedly, this may not hurt the country too much, since our record of losing out on economic opportunities far outweighs the instances when our policymakers’ commercial acumen benefitted the nation.

Most distressing, however, is to note how this ill-advised route would permit a set of technological and commercial innovations to eat into the long-term sustainability of the power market. Firstly, solar energy will keep growing amid the presence of unauthorised firms operating unchecked without a reliable quality assurance mechanism, aggravating the risks to the life and property of consumers. If connected to the grid, such substandard installations will jeopardise the electricity distribution infrastructure.

Secondly, energy storage technology is imitating the cost reduction trajectory of solar PV, stimulated by a combination of ballooning global demand and technological advancement. The continued decline in storage costs will make solar energy far more attractive for consumers who can bear capital costs. One should expect the spread of business models, such as asset leasing, to allow consumers monthly or quarterly payments, anticipated to be lower than what is charged by the Discos.

In such a scenario, consumers would draw substantially less electricity from the grid even if they decided to stay connected. Since most of these consumers — residential and C&I — would be those who pay the highest electricity tariff, the financial health of the power value chain will erode badly, exacerbating the circular debt. The power sector would face a toxic mix of commercial and security challenges.

It can be argued that this scenario is unavoidable, more specifically in terms of commercial challenges — even if more people adopt solar, capacity payments would still be made to power generation companies running on other sources. The question is if the government will just act as a bystander or actively respond to these changing dynamics.

Our policymakers are better advised to take a sensible, long-term view of the situation and articulate measures to minimise the risks identified. A judicious framework demands active involvement of the industry and other stakeholders and an effective execution mechanism for solar PV technology to pave the way for economic prosperity and much-needed energy security.