October 27, 2025

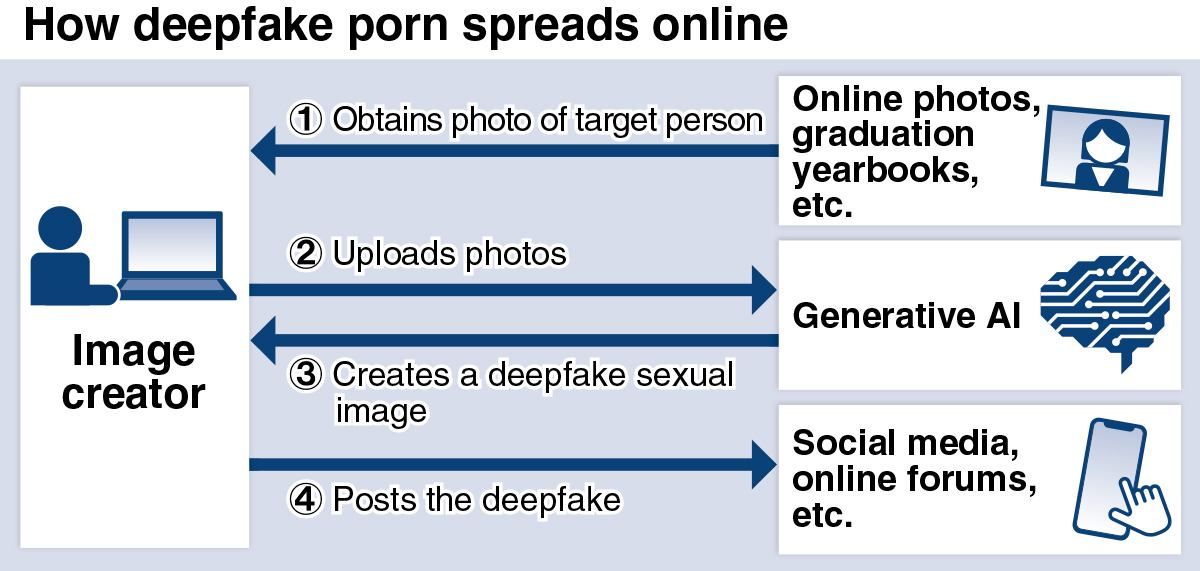

TOKYO – Deepfake pornography is increasingly causing serious harm in Japan. Such deepfakes are created with generative AI tools by using headshots of actresses and other people.

Earlier this month, a man was arrested by police on suspicion of creating and sharing sexual deepfakes of actresses. While the government has begun investigating deepfake pornography, they have yet to find a basic solution to the issue.

“I learned how to make [deepfakes] by reading articles and watching videos available on the internet,” the 31-year-old company employee in Akita reportedly told investigators. He was arrested by the Metropolitan Police Department on Oct. 15 for posting the obscene images on social media. “I was just trying to make some extra money,” he said.

The police suspect that the man used free image-generating AI software on his home computer and trained the AI on images of 262 people, including actresses, pop idols and announcers, to create 20,000 sexual images that he shared starting in October 2024.

The man reportedly was not professionally trained in IT or the use of AI. He offered subscriptions at five price tiers, ranging from $1 to $100 per month, according to the police. The MPD believe that he illegally obtained around ¥1.2 million.

To create elaborate images using generative AI, users only need to provide written instructions. The man reportedly advertised on X, and for high-paying customers would sometimes create fake images that resembled entertainers, according to the customer’s request.

Abuse of graduation yearbooks

According to a survey by a U.S. security firm, 95,820 deepfake videos were found on the internet in 2023, 98% of which were pornography. Pornographic deepfake videos produced in Japan are also flooding the internet, with targets including underage girls.

According to the National Police Agency, police received over 100 reports last year concerning deepfake sexual images of minors created with photos from children’s school events and graduation yearbooks. Most of the victims were junior high and high school students, but there were also several elementary school victims. New reports have continued to come in this year.

“The number of victims is increasing rapidly and some victims are unable to trust people because their names have been exposed,” said Sumire Nagamori, the representative of Hiiragi Net, a private internet patrol group that reports deepfake cases to the authorities. “Since many people are unaware of the harm or are unable to speak out, the cases reported are just the tip of the iceberg.”

The government has been discussing how to respond to this issue at a working group on internet use by youth that was established under the Children and Families Agency. In August, the group summarized issues to be addressed and agreed that the government should strengthen its crackdown and encourage people to ask administrators of websites hosting fake images to remove the images.

The government intends to improve its grasp of the situation, including through collecting information on cases reported to the police and schools, and compile a national plan by the end of next fiscal year.

Laws lag behind

While a stronger crackdown is needed, Japan does not have laws that directly regulate deepfake pornography, including its production. That means the police must try to cobble together a response using existing laws and regulations. In one case, the MPD was able to make a charge of displaying obscene electromagnetic recording media because the depiction was blatantly obscene.

If someone publishes a fake image created using another person’s face without permission, they may be subject to a defamation charge for damaging an individual’s reputation. One person has been accused of defamation for publishing a pornographic video in which an actress’ face was placed on another person’s body. However, there is no clear standard for judging whether the defamation charge can be applied to an AI image generated from scratch, and no one has been prosecuted for such a case, according to a senior MPD official.

Fake images depend on the image data used to train AI and instructions given when the image is created. Takashi Nagase, a professor at Kanazawa University and a former judge who is familiar with issues surrounding online representations, noted, “Even if the image resembles a real person, it may not be considered defamatory if it is not the same person.”

GRAPHICS: THE YOMIURI SHIMBUN