October 2, 2025

TOKYO – Children begin developing the skills necessary to become members of society from an early age. In Japanese schools, this process is supported by “special activities” in which children work together to improve their daily school lives, thereby learning cooperation and other essential qualities, growing into builders of a healthy democratic society.

Special activities include classroom activities, student associations, school events, and, in elementary schools, club activities. The National Curriculum Standards state that by voluntarily and practically engaging in various group activities, and by solving issues of daily life for themselves and their groups while drawing on each other’s strengths and potential, children develop the competencies necessary to be members of a community.

The competencies to be fostered are organized under three perspectives: “building human relationships,” “social participation,” and “self-realization.” Among these, the skills of “social participation” have recently drawn particular attention as the spread of social media is reshaping the nature of democratic societies.

In mid-September, I visited Urawa-Osato Elementary School in Saitama City to observe a meeting of the representative council, the core body of student association activities. This meeting is held once a month during lunch recess. Gathered in the student association room were 40 representatives: one boy and one girl from each class in grades four and up, along with the chairpersons of 11 committees, including Library, Health, and Bulletin Board.

The school has been designated as a “community school,” where residents and parents take part in school management through a School Management Council. One item on the agenda of the children’s representative council that day was “What to report to the School Management Council.”

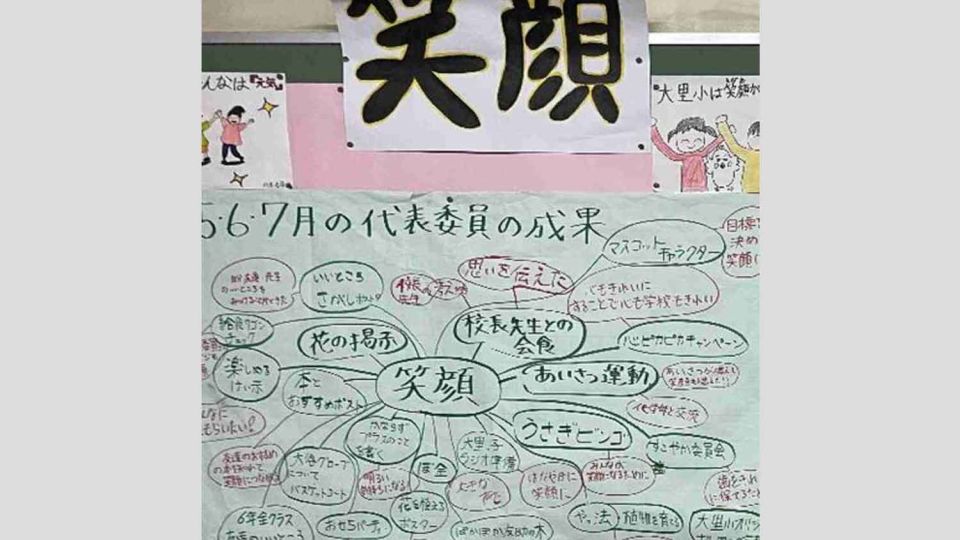

To improve school life, the representative council set this year’s school slogan as “Let’s All Smile” and, in the first term, carried out a variety of initiatives to promote communication across the school. In one campaign using worksheets, students adopted 15 small goals such as “Make eye contact when greeting,” “Say hello with a cheerful voice,” and “Say ‘great job’ to at least 10 people.” Classes colored in the relevant parts of their worksheets when 80% of the class met a goal.

“Leading the school toward achieving the slogan of smiles is the role of the representative council. Thanks to various campaigns, smiles have increased, and I think it even helped eliminate bullying,” said council chair Konosuke Kitajima, an 11-year-old sixth grader. “At the School Management Council, I want to propose joint greeting and cleaning campaigns with local residents,” he added.

The National Curriculum Standards state, “The planning and management of student councils should be carried out mainly by upper-grade students.” Yet at this school, initiatives are not limited to the older grades.

Last year, third graders created their own “greeting stamp rally” before an excursion to make sure greetings were being practiced. Since their own trial went well, the third graders decided to spread it to all classes up to sixth grade, and during lunchtime they went around to explain it to every class. They even handed out certificates to classes that achieved the goals.

“Throughout the year, we participate in various campaigns initiated by the sixth graders, and it’s always a pleasure when they bring us certificates of recognition upon achieving a goal. That made us want to create and give certificates ourselves,” recalled Kaede Saotome, 10, now a fourth grader.

“Students look forward to joining campaigns started by their seniors, and naturally begin to feel like they want to try doing something themselves,” explained Yukiko Watabe, a fourth-grade homeroom teacher in charge of special activities.

The school also has a “Long Lunch Break” on Wednesdays, when students skip cleaning after lunch. This system was proposed and realized by the children themselves. At first, Principal Midori Nakano, 55, rejected it, citing concerns over cleanliness. But the Beautification Committee students launched a thorough cleaning campaign across the school, proving that cleanliness could be maintained, and eventually won approval.

“Older students become role models, naturally drawing in the younger ones. Experiencing firsthand that they can change things by their own efforts is extremely important,” Nakano emphasized.

The special activities concept has also attracted attention abroad in recent years. In countries like Indonesia and Malaysia, some teachers and researchers are spreading the approach from the ground up. In Mongolia and Egypt, which are rapidly building new states after democratic revolutions, special activities are being introduced top-down.

Prof. Hiroshi Sugita of Kokugakuin University, an expert on special activities who provides training in Egypt and elsewhere, noted: “Interest is particularly strong in democratic countries in Asia and the Arab world that value group harmony and cooperation, such as in villages or tribes. There may be political motives to cultivate citizens who fulfill roles and responsibilities.”

In Western countries, the focus also seems to be on fostering cooperation. The documentary film “Shogakko: Sore wa Chiisana Shakai” (“Elementary school: A small society”), based on a year of filming at a Tokyo public elementary school, was released at the end of 2024 and screened across the United States, Britain, Finland and elsewhere. The shortened version spun off from this film, titled “Instruments of a Beating Heart,” was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Short Film. The film depicts everyday scenes familiar to any Japanese — school lunches, cleaning and entrance ceremonies.

International audiences responded warmly: “It is a textbook for community building” (Finland), “A good model of doing things by yourself” (United States), “The children’s sense of responsibility is amazing” (Greece), “Cooperation is nurtured from an early age” (Germany). Such praise has encouraged Japanese teachers and researchers working to improve special activities.

The film’s director, Ema Ryan Yamazaki, whose father is British and mother Japanese, attended a Japanese public elementary school for six years, studied at international schools in Japan for junior and senior high school, and later graduated from a U.S. university. “In the United States, I was praised for discipline, diligence and responsibility just for working normally. I realized that the source of my strengths was my six years of Japanese elementary school. That inspired me to make this film,” she explained during lectures this summer in Tokyo and Kanagawa. As the official English title “The Making of a Japanese” suggests, the film seems to provide, for both Japanese and international audiences, a convincing answer to why Japanese people are seen as diligent and disciplined.

Sugita, who appears in the film, warns: “Special activities are a double-edged sword.” If education uses the group as a tool, and emphasis is placed on performance or competition over cohesion and mutual help, children who sing poorly at a choral festival or who are not fast in a relay race can be seen as nuisances. “Precisely because special activities are real, failure causes real pain. But through trial and error under appropriate teacher guidance, children gain experiences that become valuable lessons for life in society,” Sugita says.

Even in early childhood education, where the focus is on language development and cooperation, the skills nurtured by special activities are already beginning to emerge. At Yagawa Nursery School in Kunitachi, Tokyo, operated by a social welfare corporation, the annual three-day “Festival Play” in July was, for the first time, entrusted to a class of 5-year-olds to plan themselves, rather than being led by teachers. The outcome exceeded expectations.

According to teacher Mizuki Fukusato, 27, a dispute arose in the food stall team between girls who wanted to sell chocolate bananas and a boy who wanted character goods. Just as they were about to decide by rock-paper-scissors, one girl suggested: “If we use rock-paper-scissors, the loser will feel bad and not get what we wanted. Why don’t we talk again?” During the renewed discussion, a compromise idea emerged: “What if we put characters on the chocolate bananas?” The children agreed.

As preparations grew demanding, teams began asking each other for help: “Since you helped us before, now we’ll help you.” Cooperation took root.

“The Festival Play gave birth to a culture of helping each other,” Fukusato recalled.

Principal Kumiko Iwai, 75, emphasized: “Even with good friends, things don’t always go your way. Knowing that others have different ideas, and repeatedly experiencing compromise, is how children grow. The role of adults is to trust and watch over them.”

Prof. Hirotomo Omameuda of Tamagawa University, an expert in early childhood education and care, praised this outcome: “It is wonderful that children themselves initiated compromise through discussion. In other words, this is education for democracy.”

Associate Prof. Kishiko Horai of Tokai University, an expert on preschool-elementary school continuity, noted: “It was important that teachers trusted the children’s abilities and left the planning to them.”

To nurture children’s ability to actively participate in society, teachers and childcare workers should consider entrusting children with more responsibilities. Of course, this requires carefully assessing each child’s developmental stage. The diverse competencies children acquire early through real-life experiences will become powerful assets for everyone to live happily in our rapidly changing society.