March 13, 2023

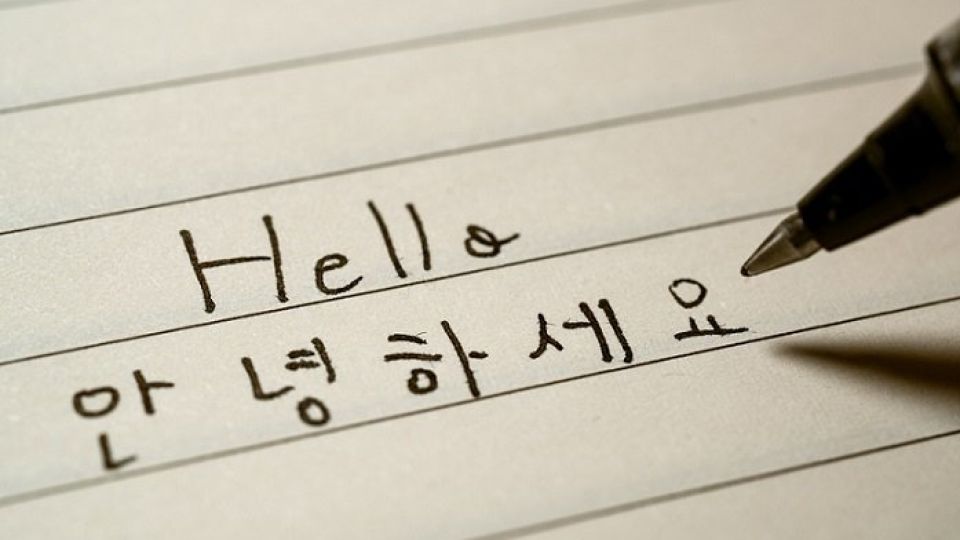

SEOUL – The following series is part of The Korea Herald’s “Hello Hangeul” project, which consists of interviews, in-depth analyses, videos and various other forms of content that shed light on the stories of people who are learning the Korean language, as well as the correlation between Korea’s soft power and the rise of its language within the league of world languages. — Ed.

When John Tae-shik Ha, a Korean adoptee to Sweden, first learned his Korean name some three decades ago, he asked the owner of a Korean restaurant in Stockholm to write it down in Hangeul for him.

Looking at the three letters that make up his name, Ha Tae Shik, he felt a sudden sense of belonging to Korea which until then seemed far removed from his life. He got his Korean name tattooed on his upper right arm.

“I got to know that my name, Tae-shik, means ‘to do something great.’ My Korean tattoo means that I’m Korean. I would never make it with western letters. As all my brothers share the ‘Tae’ in their names, I felt connected (to my birth family and Korea),” said Ha, who is 56 years old and now goes mainly by his Korean name.

Born in Seoul in 1966, Ha was adopted by a Swedish couple when he was about to turn 5 years old. After he turned 18, his mother gave him his adoption papers, which contained clues to his life in Korea, including his Korean name and family relations.

To further explore his birth identity, he began studying Korean.

Link to a forgotten identity

(From left) LiMarie Andersson, Ami Nafzger and John Tae-shik Ha.

Ha is one of many Korean adoptees learning Korean as a means of restoring their links to the country where they were born.

“For sure, learning Korean strengthened my identity as an adoptee to connect with my Korean side,” Ha said. He moved to Korea in 2002 after getting married to a Korean woman, and has run a small English hagwon in Seoul for more than 15 years.

Mads Nielsen grew up in Denmark and is now a professor of English at Sungshin Women’s University. He says being “linguistically Korean” has always been a key part of developing his ethnic identity.

“Learning Korean is not a cure for any struggles or issues adoptees may have with their identity, but it is one way to stay and feel connected with their roots no matter where they are in the world. It certainly has made me feel more Korean, even though my bond to Korea is merely language and blood, and that is enough for me,” he said.

Born in 1971 in Busan, Nielsen was sent to Denmark for adoption at the age of two. His very first trip to the land of his birth in 1986 sparked his interest in the Korean language. He studied Korean with a private tutor and by taking classes at a language institute run by Ewha Womans University.

“Studying Korean definitely opened doors and allowed for experiences I probably would not have had if I had not learned the language. I have a life in Korea, which, to some extent I could have had without knowing Korean, but the journey to living here could not have happened without having learned the language. No doubt my life has been enriched by studying Korean,” he said.

He started his career as an educator in 2010 when he worked as a Danish lecturer at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. Four years later, he landed his current job teaching English at Sungshin Women’s University.

Meanwhile, some adoptees’ birth language retention aims to establish a closer rapport with their biological families.

LiMarie Andersson, a 42-year-old Korean adoptee to Sweden whose Korean name is Oh Eun-mi, said, “Learning Korean is one step further to really get to know my Korean birth family without translators. My wish is to have a close conversation with my Korean mother and to be able to describe my inner thoughts and feelings in Korean to her.”

Andersson, who was sent to Sweden when she was just 11 months old, visited Korea in 2013 for the first time to reunite with her biological family. She started studying Korean two years ago by taking offline courses at local language institutes and private tutoring on Skype.

‘Need more public support’

Korean language learning was a means of survival for some, including Ami Nafzger, founder of Global Overseas Adoptees’ Link (G.O.A.’L.), a nonprofit organization for overseas adoptees.

“I discovered how embarrassing it was not to be able to speak Korean. I taught myself how to read and write Korean in order to survive when I needed to order food or buy something at a store,” said Nafzger, recalling the time when she first came to Korea in 1996.

Having the face of a Korean and not understanding the Korean language put her in a situation which she described as “reverse discrimination.”

“Every time I opened my mouth and spoke English, people just stared at me and some laughed at me. I found myself becoming ashamed for not being able to speak Korean or understand it,” she said.

To support other Korean adoptees who are burdened with the same language barriers, Nafzger established G.O.A.’L. in 1998. Its mission is to help fellow adoptees find language classes and translation services and to organize social events for them. In 2018, she launched another support network called “Adoptee Hub” in the US state of Minnesota, dedicated to supporting birth searches and family reunifications.

“I would like the Korean government to provide us funding so we could offer our language programs to all adoptees via Zoom and in person. The reason why Korean classes have to be catered to only Korean adoptees is that they often confront discrimination against their adoptive identity when learning the language with foreigners. These experiences could make adoptees feel ashamed or feel uncomfortable with learning the Korean language,” she said.

In April 2022, the King Sejong Institute Foundation, Korea’s state-run language education center, and the National Center for the Rights of the Child jointly launched a Korean language and culture program for adoptees, which offered both online and offline courses for 16 weeks from March 21 to July 8.

More such public language programs are needed to support Korean adoptees, especially those who have resettled in the country, the adoptees said.

“Apart from the various adoptee organizations, there are not many public facilities for Korean adoptees where they can go to study Korean or study about Korea without great expense, as far as I know,” said Nielsen.

Andersson echoed his view, saying, “Some Korean adoptees here do not even know who, what and where to ask and get help to find it, I think this should be a given part to be able to learn Korean as an adoptee so that we can understand ourselves better.”

She plans to continue with her self-study in Korean through Korean language books as well as Korean dramas.

“If I could speak Korean fluently, I would better understand the Korean culture and my ethnic identity. Also, it would be a more positive experience to not have to rely on a translator, but for the adoptee and birth family to be able to talk to each other.”

Memory of birth language

For linguists, adult adoptees’ ability to retain phonological knowledge of their native language is a research topic.

“Even decades after their adoption, international adoptees from Korea who had early life exposure to their birth language may subconsciously retain the knowledge of basic sounds, which can speed up learning the lost tongue,” said Choi Ji-youn, a social psychology professor at Sookmyung Women’s University who specializes in spoken language processing and emotion perception, in an interview with The Korea Herald.

According to her study of 29 adult Korean adoptees in the Netherlands conducted jointly by language scientists from Radboud University and Western Sydney University between 2010-2014, Dutch-speaking Koreans who were only a few months old at the time of their adoption were better at pronouncing Korean sounds than an equal-sized native Dutch-speaking control group, even if they were only a few months old at the moment of their adoption.

In the study, both groups were asked to pronounce certain Korean consonants after a two-week period of listening comprehension training and then were evaluated by native Korean speakers.

Surprisingly, it turned out that Korean adoptees received higher scores than that of Dutch participants. The research appeared in the Royal Society Open Science journal in January 2017.

This result highlighted the fact that language learning early on in life can be subconsciously retained. This subconscious knowledge can then be tapped to speed up learning of the pronunciation of the sounds of the lost tongue.

The study result implies that language learning centered on listening comprehension could be an effective study technique, according to Choi.

“Adult Dutch speakers adopted from Korea when young had no conscious knowledge of Korean, but exceeded native Dutch speakers in the acquisition of phonological knowledge about the Korean language. Their knowledge of speech sounds they learned very early on in life could have been subconsciously retained. So practicing listening and speaking skills will have a positive impact on adult adoptees’ language learning,” she said.

Choi added the fact that adult adoptees might have some subconscious knowledge of the Korean language could be a great source of motivation for them.

She also urged that there be policy efforts aimed at supporting adoptee advocacy organizations overseas.

“Support for them, including financial aid and educational assistance for Korean learners, will give Korean adoptees the feeling that their home country is taking care of them,” she said.