May 27, 2024

JAKARTA – Around this time last year, the country was shaken by the news that 70-year-old bookstore chain Toko Gunung Agung was about to close all of its remaining shops. It felt as though it was the harbinger of death for the beloved printed book.

The reality is much less grim, however. Readership is in fact growing outside the boundaries of conventional book distribution, with the erosion of traditional systems giving way to an opportunity for publishers to be closer than ever to their most important stakeholder: readers.

Take avid book reader Gustra Adyana, for example. A frequent visitor of literary festivals, Gustra often brings home travel books after listening to their authors’ passionate accounts of a memorable trip.

“It’s more convincing when I can see the author themselves and hear the book discussed,” said Gustra, who also heads the Indonesian program of the Ubud Writers & Readers Festival (UWRF).

He also checks TikTok regularly, where his favorite authors share recommendations. “It’s not uncommon for me to buy books on TikTok. So I don’t really go to bookshops anymore.”

Read also: Best-selling Indonesian authors you should be reading

Beyond bookstores

Visits to large bookshop chains show that significant portions of their stores have shifted to selling stationery, school supplies, musical instruments and other goods, with books occupying less space.

Publishers that rely heavily on traditional distribution chains are feeling the burn, especially since their industry has been slow to recover from the pandemic.

“Before the pandemic, our minimum print was 3,000 copies. Nowadays it’s 2,000. We also published six to 10 titles per month, and now [it’s] only five titles a month, maximum. It’s better now [since the pandemic], but we haven’t returned to our golden era,” said Ditta Sekar Campaka, head of marketing communications at Noura Books.

Part of this shift away from the business model of big bookstore chains is a trend toward more personalized or targeted promotions.

Even global chain Barnes & Noble successfully reinvented itself as a friendly neighborhood establishment by allowing each shop to curate its own collection based on local tastes, instead of offering a standardized selection of mass-produced books. And the bookstore staff work as matchmakers, pairing visitors with books.

It highlights an important point, that neither carefully designed product placements nor algorithmic marketing can do the job of a human worker. Every book needs a staunch supporter that will spread its messages to a broad readership, someone who will keep its spirit alive through a vast network of resellers.

“Books are a living thing,” said Windy Ariestanty from Patjarmerah, a mobile bookshop and literary festival, and publishing house Indonesia Tera.

“Accessibility isn’t just about giving people access to books. It’s also about books having the right to meet their readers.”

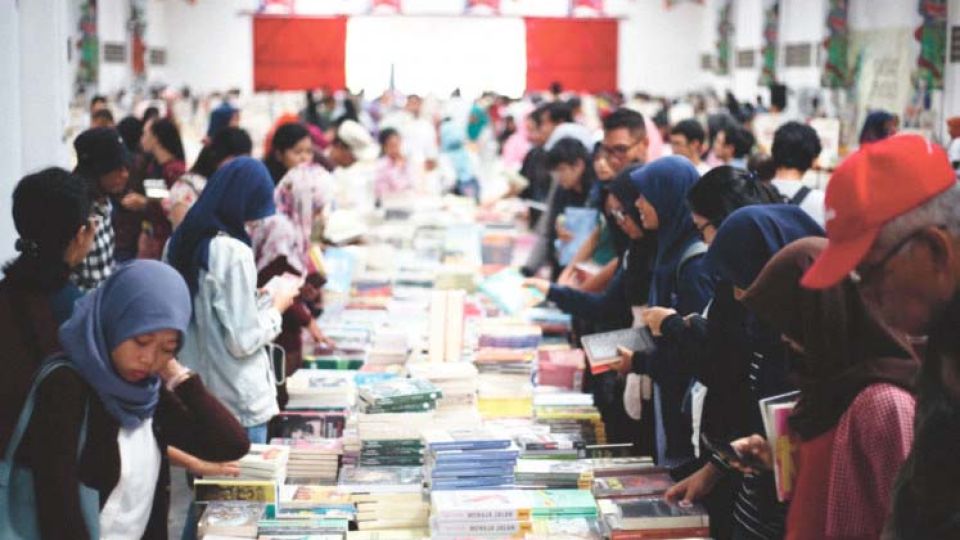

Bazaars, literary festivals, book clubs and author meet-ups are gaining importance nationwide as a platform to promote and sell books, more so than conventional bookstores.

When Windy started the Patjarmerah literary festival in 2019, dead stock items formed a significant chunk of her collection.

“These ‘dead stock’ books used to sit in the distributor’s storage. But when we sold them at Patjar Merah, people responded positively,” she recalled. “Apparently, people who read these books are not the type of people who would go to a bookstore in a mall.”

Now in its 20th edition, UWRF welcomes 10,000 visitors each year, and the Makassar International Writers Festival is still going strong in its 13th year. Meanwhile, the local branch of Malaysian mega fair Big Bad Wolf Books continues to draw readers and resellers until midnight in cities like Bandung and Balikpapan.

It’s not just literature that has experienced a revitalized relationship with their readers. Art books and zines, or self-published works with limited copies, are experiencing a revival as well.

“Comparing our last three events in 2019, 2022 and 2023, there’s a growth in terms of revenue, visitors and exhibitors,” said Januar Rianto from Jakarta Art Book Fair.

“Also, there are more art book events these days, such as in [Yogyakarta] and Cirebon. Plenty of zine festivals that started years ago then went on hiatus are also back.”

Read also: A Space For The Unbound’: Trailblazing with cultural identity

Multiple channels

Online booksellers, each with its unique community, have also become an important distribution channel.

“When the pandemic hit, online booksellers were emerging. You can say it’s them that saved Indonesia’s publishing industry,” said Windy.

No wonder that more publishers, even 12-year-old Noura Books, are increasingly relying on events or online retailers instead of traditional distributors.

“Before the pandemic, we sold 70 to 80 percent of our books through offline stores. Now, it’s around fifty-fifty with online booksellers,” said Ditta.

But these independent online booksellers are young, new and need plenty of tending to.

“Online booksellers operate on a tight margin. They typically get a 30 to 35 percent discount from publishers, and often need to give customers a 10 percent discount to encourage purchase. So their margin is just 20 to 25 percent,” said Windy.

Publishers could play pivotal roles in ensuring these sellers are thriving “by not pricing their books much lower than the resellers. That’s the least they can do”, she added.

Observing that many publishers were starting to dominate distribution channels, Windy remarked, “That can kill the ecosystem. A monopoly is never good.”

Nevertheless, the rise of independent retailers has given new life to publishers.

“Something new in the last 10 years is the alternate universe genre, which is similar to fan fiction. I think it emerged because of the Korean Wave,” said Ditta of Noura Books.

“Fans of certain boy bands would make fictionalized stories of the [band members],” said Ditta, pointing to the novel Azzamine, published by Bukune, a story about a love triangle that started as a Twitter thread and took Na Jaemin of South Korean boy band NCT as its inspiration.

She added that “many new publishers used this opportunity. And their preorder can exceed 10,000 copies. It shows that young people do read!”

Ditta also saw a spike in interest in children’s books.

“There’s a massive movement among young mothers who are more educated, called Read Aloud [Indonesia]. These mothers want their children to [start reading] early. For them, reading is a primary need, not a secondary one. So they are willing to spend a lot of money on books,” she said.

“In fact, during the pandemic, we sold premium packages of children’s books that cost more than Rp 1 million [US$63], and they sold out fast.”

Meanwhile, Windy focuses on “evergreen” books. One of its bestsellers, Merahnya Merah (Red is red), a story by Iwan Simatupang about homeless people in metropolis, was first published by Djambatan in 1968 and then reprinted by Indonesia Tera in 2020.

Even so, “its sales remain constant to this day. This is one of the books [that] we insist on keeping printing because of its philosophical weight” she said.

Though visitor footfall at bookshops is slowing down, it is clear that people have not stopped buying and reading printed books. In fact, these days, with ever more options in terms of titles, genres and distribution channels, it’s easier to discover books that truly hit home.

Read also: Celebrating women on screen and in print