September 4, 2023

ISLAMABAD – PROTESTS against a sharp increase in electricity prices flared up across the length and breadth of the country as the month of August 2023 neared its end, with the inflation-weary citizenry taking to the streets to burn bills and vent their anger against power utilities. Why had the citizenry taken weeks to wake up to a decision made by the PDM government in July, and what are the factors behind the sudden jump in the price of electricity?

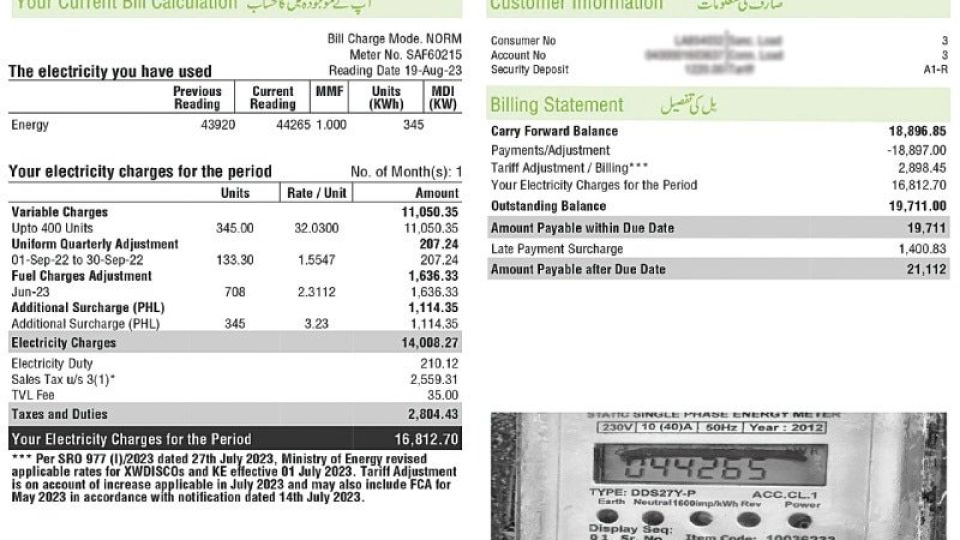

Nepra, the federal authority that sets electricity prices for all power consumers in Pakistan, recently announced a revised electricity tariff that became effective from July 1. The tariff for residential consumers — which is the same for consumers all over the country — was increased by as much as Rs7.50 per unit, or 27 per cent. Even though the increase in prices was substantial, most citizens remained unaware of the big hit they were about to take for weeks because of the timing of a key notification.

The new electricity tariff was okayed in the last few days of July, more than three weeks after the date on which it was supposed to come into effect (July 1). By that time, most electricity companies — or DISCOs, as they are properly known — had already dispatched July’s electricity bills to their customers based on the old tariff. However, because they had been lawfully allowed to charge customers a higher tariff from July 1, they were told to cover the difference in the old and new rates through the next bill — ie, the bills for the month of August.

Meanwhile, the PDM government, which had actually lobbed this electricity price grenade at the unsuspecting citizenry, quietly packed up and exited the picture on August 10, leaving it to the caretaker set up to deal with the aftermath of its decision.

Snowballed

Your electricity billing cycle does not follow the calendar: ie, your August bill is not a bill for electricity consumed in the month of August alone. For logistical reasons, electricity companies send meter readers to get readings from specific areas on different days of the month. On the assigned date, a meter reader(s) comes up to your home, takes a picture of your meter’s display as ‘proof’ of your usage, records the reading in his device, and later reports it back to the company. If your meter is read every 10th day of the month, your electricity usage of the first 10 days of the month, as well as the preceding 20 days of the previous month, are therefore factored into the company’s calculations for your bill.

In our example, the ‘August’ bill received by a customer would, therefore, be based on their electricity consumption in the one-month period from July 10 to August 10, and calculated using the higher tariff since it was in effect by that period. However, because the companies also needed to recover the difference in the lower rate they had charged in the customer’s July bill and the new tariff, the higher tariff — which was applicable on any units consumed between July 1 to July 10 — was also adjusted in the August bill.

For another customer, however, their August bill could cover the period from July 24 to August 24. Assuming that these two customers used the same amount of electricity in both months, the second customer would have received an even higher bill because it would have included an adjustment for the 24 days of July they were earlier undercharged for, compared to the first customer’s 10.

Due to the staggered nature of Discos’ billing cycles, the number of people becoming aware of the new tariff only started increasing as time went on and more and more batches of customers received their bills. Widespread protests eventually broke out when the number of people who had received electricity bills under the new tariff reached a critical mass around the middle of the month.

Breaking down the bill

Before getting into a discussion on why electricity suddenly seems so unaffordable, it is important to understand how the price of each unit of electricity is determined, and how energy is billed to domestic consumers. Here’s a look at the various components of an electricity bill you can expect to receive if you do not qualify to be considered a ‘protected’ consumer.

Variable charges are calculated based on your monthly consumption and the tariff approved by Nepra. This tariff is calculated based on several underlying costs, which can broadly be categorised as:

The power purchase price, which includes capacity charges, energy charges (cost of fuel) and operation and maintenance charges demanded by independent power producers and publicly owned power generation companies (Gencos); a Use of System charge, which goes to the NTDC, which ‘transmits’ power through the national grid; the Distribution Margin, which includes operation and maintenance costs for Discos, their salaries, wages and other benefits, depreciation, opex and other expenses, as well as allowed profit; and, finally, transmission and distribution losses, which account for theft of electricity and the loss of electricity during transmission due to poor infrastructure.

On top of the electricity tariff, the following charges are added (and sometimes subtracted) from your bill.

Fuel Charge Adjustment

Electricity utilities may add a Fuel Charge Adjustment for the previous month to the bill after getting approval from Nepra. This charge covers any extra cost they incurred in the production of electricity above the tariff they have been allowed. It varies with changes in the cost of fuel, variations in the types of fuel used to generate electricity (called the generation mix) or any costs incurred due to changes in generation volume.

Uniform Quarterly Adjustment

A Uniform Quarterly Adjustment charge may also show up on your bill periodically due to many of the same reasons as a fuel charge adjustment. However, quarterly adjustments also take into account variations in transmission and distribution losses, the exchange rate, capacity payments to IPPs (which are made in dollars), prevailing interest rates (which affect financing costs), as well as several other factors.

PHL surcharge

The PHL surcharge is, to put it simply, the price the government forces bill-paying customers to pay for its own failure to manage circular debt in the power sector. It is currently as high as Rs3.23 per unit for anyone who consumes more than 300 units of electricity or is billed under a Time of Use tariff. ‘PHL’ stands for Power Holding Limited, a company established to fund the ballooning payables to power sector entities. The amount recovered from this levy is used to pay off the interest on loans granted by PHL to various players in the power sector.

Electricity Duty

The Electricity Duty is a provincial tax levied at a rate of 1-1.5pc for domestic users. As such, it is a negligible component of the bill.

TV License

The TV License fee is a charge used to subsidise PTV, which remains unable to achieve operational sustainability on its own.

Sales Tax

Finally, the government adds 17pc as its own cut from the total bill as a General Sales Tax.

Income Tax

The income tax is the last piece of bad news. If, after the sales tax has been added on, your bill crosses the Rs25,000 threshold, you become liable to be charged another 7.5pc of the total as ‘withholding income tax’. This is just a fancy way if making ordinary citizens pay for the Federal Board of Revenue’s failure to get tax cheats to pay up.

This tax is, however, waived if you live in a property that is registered to an active taxpayer.

Why has there been such a massive increase in electricity prices?

Very simply, the electricity tariff has increased sharply due to the last government’s failure to adequately manage the financial crisis. Thanks to the wizard who led the finance ministry till the PDM government’s last days, the country no longer has enough in the kitty to continue subsidising electricity for most electricity consumers. The focus is now on protecting the most vulnerable — particularly those who do not consume more than 200 units of electricity in any given month. Everyone else is being made to shoulder the entire burden of the inefficiencies building up in the power sector over the past few decades or so.

As mentioned earlier, the electricity tariff includes a large component that just goes towards paying IPPs what industry people call ‘capacity charges’. These ‘capacity charges’ are simply payments that are guaranteed to IPPs whether or not they actually make any electricity. These charges will top Rs2 trillion in 2024, and these will need to be covered, for the most part, by ordinary people.

Capacity payments were made part of IPPs’ contracts because our state once believed they were necessary to make it more financially attractive for private firms to invest in the country. However, the governments responsible for these agreements grossly overestimated the benefits of these agreements, and we are now in a situation where we’re damned if we buy power from these IPPs, and damned if we don’t.

Capacity charges have mostly become a headache because they are indexed to the exchange rate, domestic interest rates and foreign interest rates, among other factors. None of these has moved in a favourable direction for Pakistan over the past year, thereby increasing the cost burden of these contracts without any net benefit for the country.

Another component of the variable charges are transmission and distribution losses, which can broadly be categorised into losses due to electricity theft, and losses arising from the poor state of the transmission infrastructure. Data shows that some power distribution companies — such as those operating in Peshawar and Sukkur, for example — are responsible for substantially higher theft of electricity compared to, for example, Islamabad, Karachi or Lahore. However, because of the government’s policy to have a uniform tariff across the country, the cost of this theft is eventually shared by all bill-paying customers all over the country. Bill-paying customers also pay the bill for around 190,000 lucky households that receive electricity almost free of charge from the state.

So, can the government give end users any relief? The answer is yes, and no. The government can start by cutting some of the taxes added onto electricity bills, especially the PHL surcharge and the withholding income tax. Both these taxes have been levied because of the failures of the power sector and the FBR to do their jobs, and it is unfair that ordinary people should pay for these inefficiencies when they are facing unprecedented financial stress themselves. The revenue shortfall ought to be covered by taxing the undertaxed retail and real estate sectors, and pushing the FBR to be better at its job. The rest of the measures discussed by analysts are more technical and for experts to figure out. They also need considerable time. They chiefly involve resolving the issue of high transmission and despatch losses, ensuring the availablity of fuel, especially gas, on rationalised prices, prioritising more efficient generation plants over others, and so on.

In conclusion, it must be underlined, highlighted and stressed that the poor meter reader or worker assigned by your power utility to disconnect your power supply or take meter readings has no role in this entire mess. It is tragic that these ordinary workers have been facing the brunt of the public’s anger, when the actual culprits are still spouting nonsense and pointing fingers at each other without taking any responsibility for past mistakes.