January 15, 2025

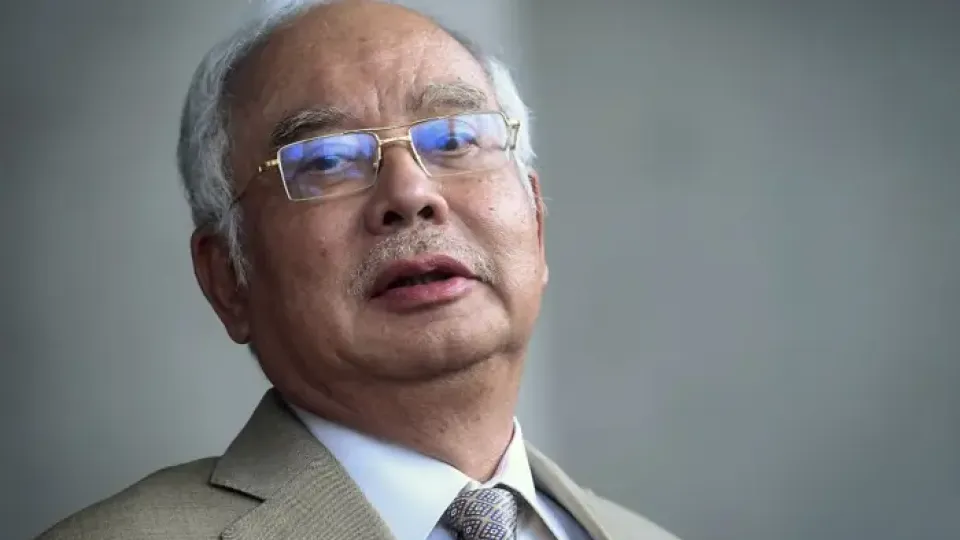

KUALA LUMPUR – The Malaysian government’s move to apply for a gag order to stop discourse on former prime minister Najib Razak’s application for house arrest has sparked backlash from politicians and experts, who question its purpose.

Constitutional law expert Shad Saleem Faruqi told The Straits Times that a gag order is “too late and futile”, seeing as discussions on the matter are already in the public domain.

“This gag order appears to be too late because the issue has been openly discussed in Parliament and the media,” said Professor Shad, who lectures at the University of Malaya.

On Jan 13, Deputy Public Prosecutor Shamsul Bolhassan said the government will file an application to prohibit discussion on Najib’s attempt to serve the rest of his prison sentence at home.

The application will be filed in court by Jan 20, he said.

Najib was in 2022 sentenced to 12 years’ jail for corruption linked to the multibillion-dollar scandal involving state fund 1MDB.

In January 2024, the Pardons Board chaired by Malaysia’s then King, Sultan Abdullah Ahmad Shah, decided to halve Najib’s 12-year jail term and slash his RM210 million (S$63.6 million) fine to RM50 million.

Najib has claimed there exists a royal addendum to that decision that entitles him to serve his prison sentence at home.

On Jan 7, Najib won a legal challenge allowing his house arrest case to be heard in Malaysia’s High Court. He is seeking a court order compelling the government to verify and execute the royal addendum.

Since then, Malaysia’s opposition and factions within Najib’s party, Umno, have exploited the issue by claiming the ruling government and Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim had kept the royal order under wraps. These claims have been denied by Datuk Seri Anwar.

Applying for the gag order only creates a negative perception of the government, said Umno Supreme Council member Mohd Puad Zarkashi in a Facebook post on Jan 14. He also urged the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC) to retract its application.

“This will create a trust deficit towards the government. Prohibiting the public from discussing the royal addendum will make the public believe that there are more secrets being hidden. There’s a lot of speculation and negative assumptions on social media,” said Datuk Puad. “This will have an adverse impact on the government’s credibility.”

Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Law and Institutional Reform) Azalina Othman Said told the media on Jan 14 that there should not be a gag order on Najib’s case, as the issue is already out in public and discussions on it will continue. She said the issue would also likely be discussed when Parliament reconvenes on Feb 3.

Still, she stressed that the judiciary should be allowed to make an independent decision on the matter.

“To be fair, I think the AGC has its own legal reasons, and they will file a formal application (for the gag order). So let the court decide on the matter,” she said.

The gag order has also sparked criticism of Mr Anwar and his Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition, which had long championed freedom of speech when it was in the opposition.

Mr Anwar has had to strike a balance between keeping key coalition ally Umno happy and maintaining his reputation as an anti-corruption reformist among his own supporters.

A lawmaker from opposition Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia, Datuk Wan Saiful Wan Jan, told The Straits Times that the government’s move to stop even MPs in Parliament from discussing the issue reflects poorly on Mr Anwar.

“Anwar isn’t a friend of freedom of speech. The whole administration is working hard to curb freedom of speech in Malaysia through various angles and this is another element of that effort,” said Mr Wan Saiful.

In 2016, when Najib was prime minister, Malaysia’s lawmakers were prevented from raising questions about the 1MDB debacle by a gag order put in place by then Parliament Speaker Pandikar Amin Mulia. Mr Anwar’s colleagues in PH, which was the opposition in 2016, protested vehemently against the directive.

The order was lifted in August 2018, after PH came to power.

Opinion research institute Merdeka Centre’s programmes director Ibrahim Suffian told ST that the application for the gag order is not to limit public discourse but to protect the royal institution.

“I believe the principal reason behind the application is because it infringes on the prerogative of the palace. If the debate continues, it will affect public opinion towards the King and the government wants to avoid it,” he said.

The success of the government’s application to restrict freedom of speech will depend on whether it falls within permitted grounds set out in the Constitution, said Prof Shad. These include considerations like whether the restriction is in the interest of public order, if such discussions are in contempt of court, and to protect the sovereignty of the rulers.

“I think the challenge for the AGC to obtain the gag order is to find a restriction (on freedom of speech) that is within permissible grounds enumerated in the Constitution,” he said.

- Azril Annuar is Malaysia correspondent at The Straits Times.