June 27, 2025

KUALA LUMPUR – Researchers in Britain have come up with a simpler, quicker and non-invasive way of monitoring Barrett’s oesophagus, a precursor to oesophageal cancer.

The current method of monitoring is via endoscopy, where a long tube with a camera is inserted through the mouth and down into the oesophagus.

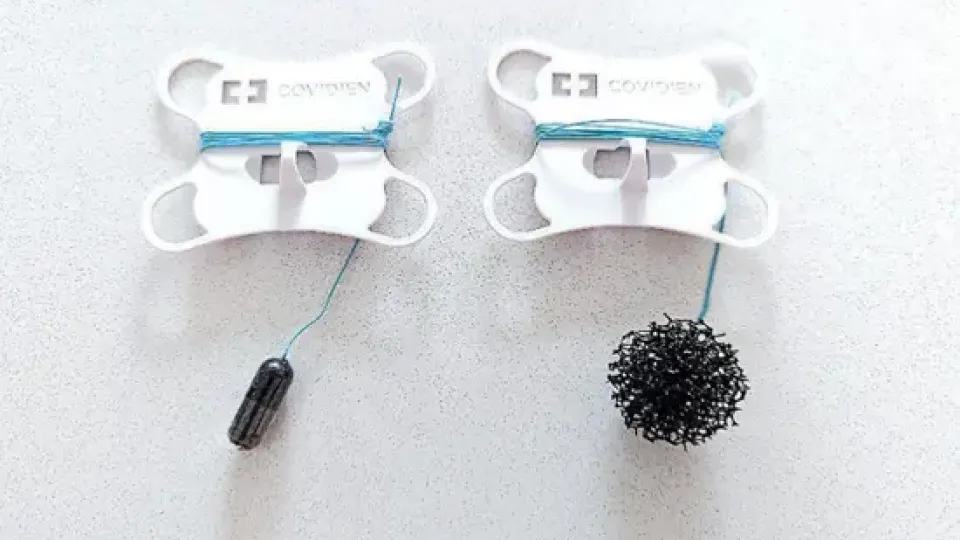

In contrast, the team from the University of Cambridge have developed a capsule sponge, which comes in the form of a small capsule attached to a string.

The patient only has to swallow the capsule, which will release a small sponge upon dissolving in the stomach.

The sponge is then gently pulled back up through the oesophagus via the string, collecting cells for analysis along the way.

According to team member and Cancer Research UK Clinical PhD Fellow Dr Tan Wei Keith, the whole process only takes about 10 minutes, does not require sedation, can be done in the clinic by a nurse, and is much cheaper than endoscopy.

Identifying risk levels

The researchers also investigated whether the capsule sponge test could be used to accurately identify Barrett’s oesophagus patients who are at higher risk of developing cancer.

Their study, published in The Lancet medical journal on Monday (June 23, 2025), included patients from 13 British hospitals.

Says Dr Tan, the study’s lead author: “We analysed the cells collected from the sponge for early signs of cancer and tried to estimate the individual’s cancer risk – a process known as risk stratification.

“Our key finding was that the capsule sponge can reliably identify which patients are low risk and which are high risk, allowing us to prioritise patients who truly need further investigation or treatment.

“This is the first major study showing how this tool can be used not just for diagnosis, but for long-term monitoring, safely reducing the need for repeated endoscopies in many patients.”

He adds: “Doctors can therefore focus their time and endoscopy resources on the people who really need it most.

“This will ease the burden on endoscopy services, shorten waiting times, reduce costs and improve access to care within overstretched healthcare systems.”

In addition, he shares that, as a Malaysian, it is a tremendous achievement for him personally be published as the first author of a research paper in The Lancet, one of the top medical journals in the world.

“To my knowledge, very few Malaysians have done so.

“The only other example I’m aware of is Professor Wu Lien-Teh, who published his pioneering work on the Manchurian plague in The Lancet more than 100 years ago, in 1911.

“He was later nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

“To follow even in a small way the footsteps of one of Malaysia’s most respected physicians is an incredible honour,” says Dr Tan, who is training to become a gastroenterologist and hepatologist.

Catching it early

Oesophageal cancer is the seventh most common cancer worldwide and the sixth most deadly.

Dr Tan notes that: “Less than 20% of patients survive five years after diagnosis.

“This is largely due to patients presenting late, such that when symptoms appear, the cancer often has spread to other organs, making it harder to treat.”

Having Barrett’s oesophagus increases the risk of cancer, specifically oesophageal adenocarcinoma, by up to 40 times.

“In Barrett’s, the normal cells lining the food pipe begin to change and resemble cells from the intestine – a process called intestinal metaplasia.

“Over time, these abnormal cells can become irregular and develop into early stage cancer,” he says.

Catching the cancer early means that the patient can have the cancer cells removed via endoscopy with excellent long-term outcomes, rather than potentially having to remove their entire oesophagus and undergoing chemotherapy as needed in advanced cases.

Dr Tan shares: “I’ve seen firsthand how deeply (cancer) impacts not only patients, but also their families.

“Some of my family members and friends were diagnosed too late, when treatment was no longer possible.

“That experience made me reflect on how crucial early detection of cancer can be.”

He adds: “Barrett’s oesophagus is a perfect example of how detecting and treating a precancerous condition early can prevent cancer and potentially avoid surgery.

“This approach, known as organ-sparing treatment, can be both highly effective and life-changing.

“Helping someone avoid a major operation while still curing their cancer is one of the most meaningful things we can do as doctors and researchers.”

While the capsule sponge test is not currently available in Malaysia, Dr Tan and his colleagues hope to work with local partners to introduce it in the near future.

“This is especially relevant as the number of people with acid reflux and obesity is increasing in Malaysia and the region, which raises the risk of oesophageal cancer,” he says.

He adds that he hopes to be back in Malaysia in the near future to contribute his experience and knowledge from his time in Cambridge to help elevate the standard of healthcare in the country in the early detection of cancer.