March 3, 2025

SINGAPORE – As a teenager, Ms Tan knew she did not want to have children.

The 49-year-old professional, who declined to give her full name, said: “Having a child is a huge responsibility, and I don’t want to be responsible for another life and how they turn out.

“I also value my freedom a lot, and the ability to live my life the way that I want.”

Like her, a growing number of married women are remaining childless at the end of their child-bearing years – either by choice or not.

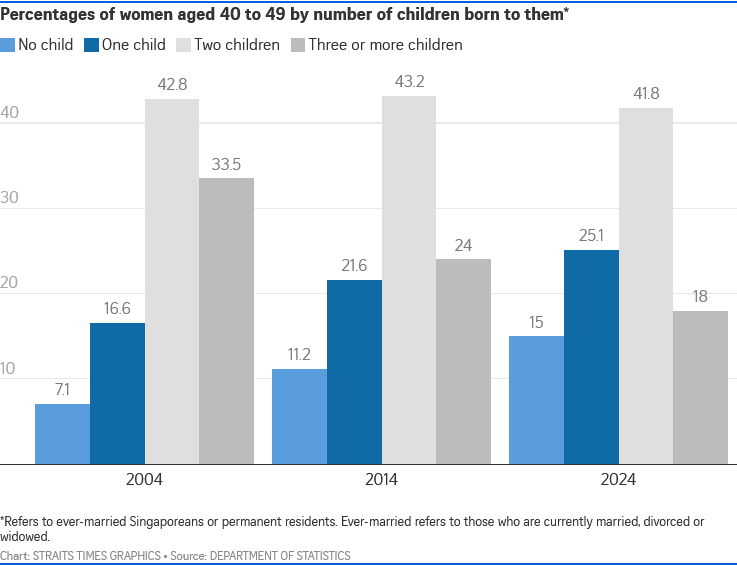

On Feb 18, the Department of Statistics released figures showing that in 2024, 15 per cent of resident ever-married women aged between 40 and 49 have no children. This is double the 7.1 per cent in 2004.

In 2014, the figure was 11.2 per cent. Ever-married refers to those who are currently married, divorced or widowed, while residents refer to Singaporeans and permanent residents.

Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) senior research fellow Tan Poh Lin described the increase in the proportion of childless couples as “very rapid”.

The latest statistics come amid a push by the Government to support large families – defined as those with three or more children – and spur Singaporeans to have more babies.

In his Budget speech on Feb 18, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong announced that families will get up to $16,000 in additional support for each third and subsequent Singaporean child born on or after Feb 18, as part of the new Large Families Scheme.

For the couples interviewed by The Straits Times, the decision not to have children was due to lifestyle preferences, negative childhood experiences and the fear of the immense responsibility of raising children, among other reasons.

For example, Ms Tan and her husband, a professional who is a few years older than her, enjoy travelling and “exploring life”. She said that having children would restrict the things they are able to do, such as going on holidays at a short notice.

She also prefers to spend her time volunteering for the causes she believes in, such as empowering women with equal opportunities and pursue her diverse interests.

She also does not want to go through the stresses she sees her friends face with their children’s studies, and raising a child in today’s world is more complex than before, she said.

A general manager who wanted to be known only as Mr Chin, and his wife also have no children by choice. He is 41 while his wife is in her 40s.

“The unknown is too much for me to take the step of having kids. Will the child turn out all right? Will I be an all right parent?”, he said. “Mentally, it’s too much of a burden to bring up someone.”

He and his wife have been married for six years and have three cats.

Those interviewed say they did not face any pressure from their parents, in-laws or society in general to have children.

Ms Tan said: “I think we are in an era where personal fulfilment is a lot stronger than in the past. The sense of self is also greater than sacrificing for someone else’s definition of the greater good.”

Professor Jean Yeung, director of social sciences at the A*Star Institute for Human Development and Potential, said that the growing trend of married couples remaining childless marks a “significant societal transformation as marriage becomes increasingly decoupled from the expectation of parenthood”.

Historically, married couples were expected to have at least one child, as marriage serves as the means to continue the family line, noted Prof Yeung, who is also a professor at the National University of Singapore’s Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine.

But it is now more socially acceptable to remain child-free, given the growing number of “double income, no kids” (Dink) couples, she said.

Prof Yeung added: “This decoupling allows couples to redefine what marriage means to them, focusing on companionship, mutual support, and shared economic or personal goals, not necessarily to have children.”

In 2024, the total fertility rate (TFR), which refers to the average number of babies each woman would have during her reproductive years, remained at 0.97, the same as in 2023. This is one of the lowest in the world.

The hoped-for Dragon Year effect, which boosted the TFR in 1988, 2000 and 2012, did not materialise in 2024.

In the Chinese zodiac, the Dragon Year has traditionally been considered as auspicious for having children, as the dragon is associated with good fortune and leadership, among other desirable traits.

On Feb 28, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office Indranee Rajah said in Parliament: “The Dragon Year effect has been diminishing over the years, reflecting the generational shifts in attitudes and priorities among young couples.”

And with a lot more couples remaining childless, this will further dampen the TFR and also lead to changing family structures, said the academics interviewed.

IPS senior research fellow Kalpana Vignehsa said: “We will have to get increasingly comfortable with higher levels of immigration or lean heavily into artificial intelligence (AI) technology in the hope that effects of a shrinking workforce can be mitigated through AI.”

At the same time, some couples yearn for children but have been unsuccessful in their quest to become a parent.

Mr Tan, a 36-year-old professional who declined to give his full name, and his wife, 36, initially wanted to have three children. They have been married for four years.

Their hopes were dashed when Mr Tan discovered he has fertility issues. The couple have since tried three cycles of in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment at private hospitals without success.

The IVF treatment was not only costly – the couple have spent about $35,000 so far – but it was also emotionally taxing for them.

Mr Tan said he struggles with self-esteem issues and guilt after learning that their infertility woes originated from him.

He said: “Some friends are well-meaning but insensitive, and they recommend all sorts of remedies (to boost fertility). And many people don’t know how to respond to our struggles; they either stay silent or laugh it off.”

The couple now plan to try another cycle of IVF at a public hospital where they can get subsidies, as Mr Tan say they can no longer afford treatment at a private hospital.

He hopes the Government would consider subsidising the IVF treatment at private hospitals as well in the Republic’s quest to boost birth rates.

Mr Tan said they chose to take the private route initially, as they heard the wait to start treatment at public hospitals is longer.

The Government co-funds up to 75 per cent of the cost for eligible couples undergoing IVF and other assisted reproduction treatments at the KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, the Singapore General Hospital and the National University Hospital.

He said: “I don’t know how many more cycles (we will go through), but we are not going to give up.”

- Theresa Tan is senior social affairs correspondent at The Straits Times. She covers issues that affect families, youth and vulnerable groups.