December 19, 2024

SEOUL – For many young Koreans, the events following President Yoon Suk Yeol’s martial law declaration were not only bewildering in their context, but also jarring in terms of the language being employed.

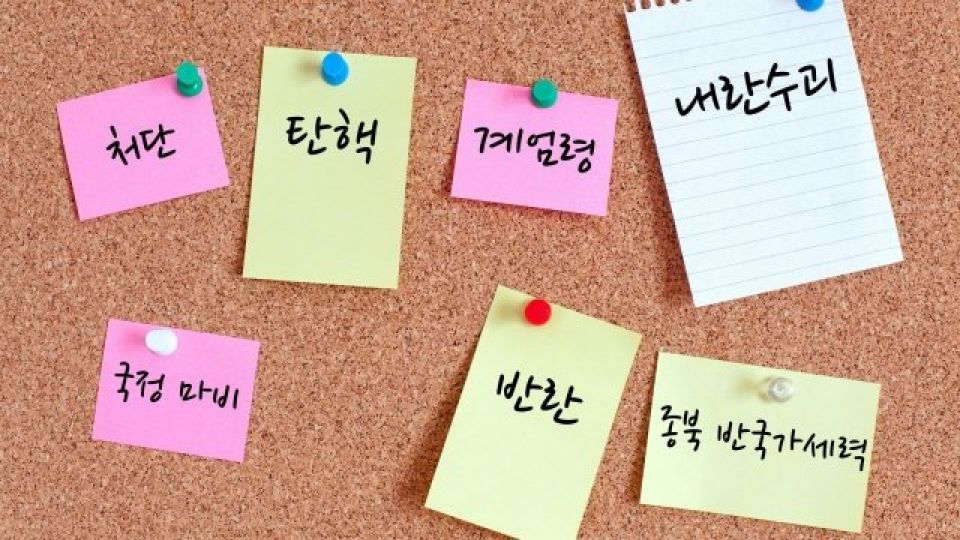

Terms that once seemed confined to history books and law textbooks — “martial law,” “treason,” “insurgency,” “insurrection,” “anti-state forces” — suddenly crossed over into daily news. The vocabulary felt foreign to many young Koreans, while the exact meanings remained unclear.

Indicative of this, “gyeoemryeong,” the Korean term for “martial law decree,” surged to become the second most searched-for term on Google in South Korea this year, driven by explosive growth in searches for its definition since the imposition of martial law on Dec. 3.

Several Koreans in their adolescence and 20s whom The Korea Herald talked with admitted to having struggled to understand certain terms as the high-tension political drama unfolded. Social media platforms and online searches became essential tools for seeking clarity, they added.

High school student Lee Hyun-woo recognized terms like “martial law” and “impeachment” from his history and law classes, especially in the context of Korea’s 2016 impeachment of President Park Geun-hye. However, he found words like “cheodan,” a term used in the martial law order to refer to punishment of rule breakers, and “naeran sugwae,” meaning the mastermind of insurrection, to be confusing. “I questioned my own knowledge because of how easily these words were used by news outlets. It was all new to me,” he admitted.

The last time martial law was imposed in South Korea was some 45 years ago, during the late 1970s under military dictatorship.

Having grown up in a democratic South Korea, Park Jung-bin, a university student in her 20s, was afraid when she first heard the news of martial law. “I had only seen the term in history books,” she said. “It conjured up an image of soldiers suppressing people. Seeing it today was terrifying.”

At first, she mistook “naeran sugwae” for something related to anti-communist rhetoric, but later learned the true meaning. She also began to question how terms like “cheodan,” which has a dictionary meaning of disposition but carries a much harsher connotation akin to execution, remain relevant today.

Park Yoon-ji, another university student in her 20s, echoed similar sentiments. “It’s a shame that such words need to be revisited,” she said.

The situation has been particularly confusing for younger students. When a second grade teacher mentioned martial law in a discussion about democracy, the children were puzzled. They asked, “What is ‘cheodan’ (punishment)?”

Middle school students shared in this confusion as well. Kim Yoon-sang admitted, “I’ve never heard words related to martial law, except for the term ‘martial law’ itself.” He added that he only understood it after his teacher explained it.

For 12-year-old Kang Min-je, watching the news provided little clarity. “It felt like a made-up political scenario with made-up words, not something happening in real life,” he said.

For foreign residents and students, the resurgence of these historical terms has been particularly jarring. Rachel Perry, a 21-year-old exchange student with only a year of Korean studies, had never heard such terms before.

“I remember (when I first heard the news) thinking these were the last words I should be learning. Yet, I now know them very well.”

Caliman Oana Maria, 24, who has taken classes in Korean at a local university for over two years now, found vocabulary related to Yoon’s impeachment and martial law was too complex to navigate. “I relied solely on English media outlets to understand what measures I should take,” she said.