March 15, 2023

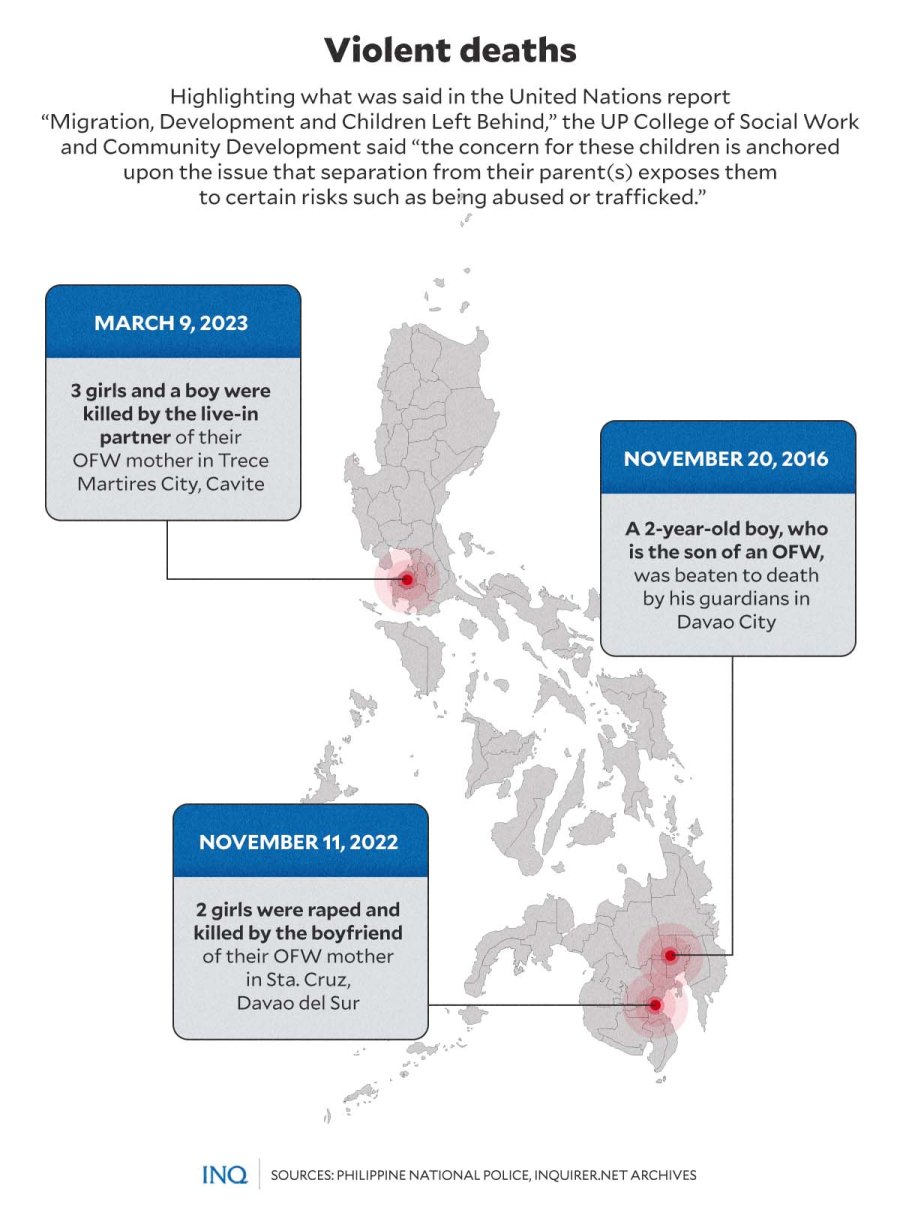

MANILA – The dreams of an overseas Filipino worker (OFW) for her children came to a tragic end last March 9 when her four children—three girls and a boy—were killed by her live-in partner in Trece Martires City, Cavite province.

Virginia Dela Peña, an OFW in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, returned to the Philippines last March 11 and went straight to Taysan, Batangas but not for the kind of reunion that she and her children had been waiting for years.

She came back to grieve over the death of four of her five children, who had been stabbed and killed by her live-in partner, who eventually killed himself after the massacre of the victims, who were only 14, 12, 9, and 5 years old.

The tragedy was so serious that it prompted the Department of Migrant Workers (DMW) to look at developing a program to care for the children of OFWs, who are left to non-parents, to prevent a repeat of the violence that killed the children.

Migrant Workers Secretary Susan Ople said she will engage the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) in a discussion on how they can assist the children of OFWs left to next of kin or household members other than the actual parents.

As Ople explained to INQUIRER.net on Tuesday (March 14), she talked to Social Welfare Secretary Rex Gatchalian since “they have a program for children.” She said the DMW has existing programs, too, but these still need to be strengthened.

“It is critically important that there is a unit within the department that is dedicated for family relations—a unit that can formulate policies and programs to address the social costs of labor migration,” she said.

Ople made clear, however, that what she said is “not yet concretized,” stressing that a care program for the children of OFWs “really needs to be a product of technical planning, technical work.”

Violent, grievous deaths

The death of Dela Peña’s children is not the first case of OFW children being abused or killed by people trusted to care for them while the parents are away to work and provide a better future for them.

In 2016, a 2-year-old son of an OFW in Bahrain was also killed after being beaten to death by his guardians in Davao City, who allegedly got irritated when the child peed his pants.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The boy had been rushed to a hospital but was declared dead on arrival. He suffered multiple injuries. His mother, Erlinda Cagalitan, believed that her son suffered physical abuse.

ADVERTISEMENT

Last year, two children—15 and 11 years old—were raped and killed in Sta. Cruz, Davao del Sur by the boyfriend of their mother, an OFW in the Middle East. The victims had been stabbed and shot to death.

As the police said, the bloodied bodies of the two girls were discovered on November 11, 2022 after a neighbor, who heard the victims screaming for help, went to their house to check on the children.

Both suspects in the killings in Davao City and Davao del Sur had already been arrested.

Back in 2017, the Mindanao Migrants Center for Empowering Actions Inc. (MMCEAI) in Davao City said it has documented a total of 132 cases of children of OFWs being abused and molested.

Its executive director, Inorisa Sialana-Elento, had said from 2014 to 2017, the MMCEAI data indicated that there were several cases of abuse against children of OFWs, who were also found to be in a constant state of “worry and fear.”

Concern for left-behind children

As stressed in a study written by community development expert Mark Anthony Abenir and published by the University of the Philippines’ College of Social Work and Community Development, “left-behind children of migrating parent(s) have become a matter of growing concern to the global community.”

Highlighting what was said in the United Nations report “Migration, Development and Children Left Behind,” Abenir said “the concern for these children is anchored upon the issue that separation from their parent(s) exposes them to certain risks such as being abused or trafficked.”

As Ople said, “the risk of having one or both parents [working] overseas is the increased vulnerability of the children left behind.”

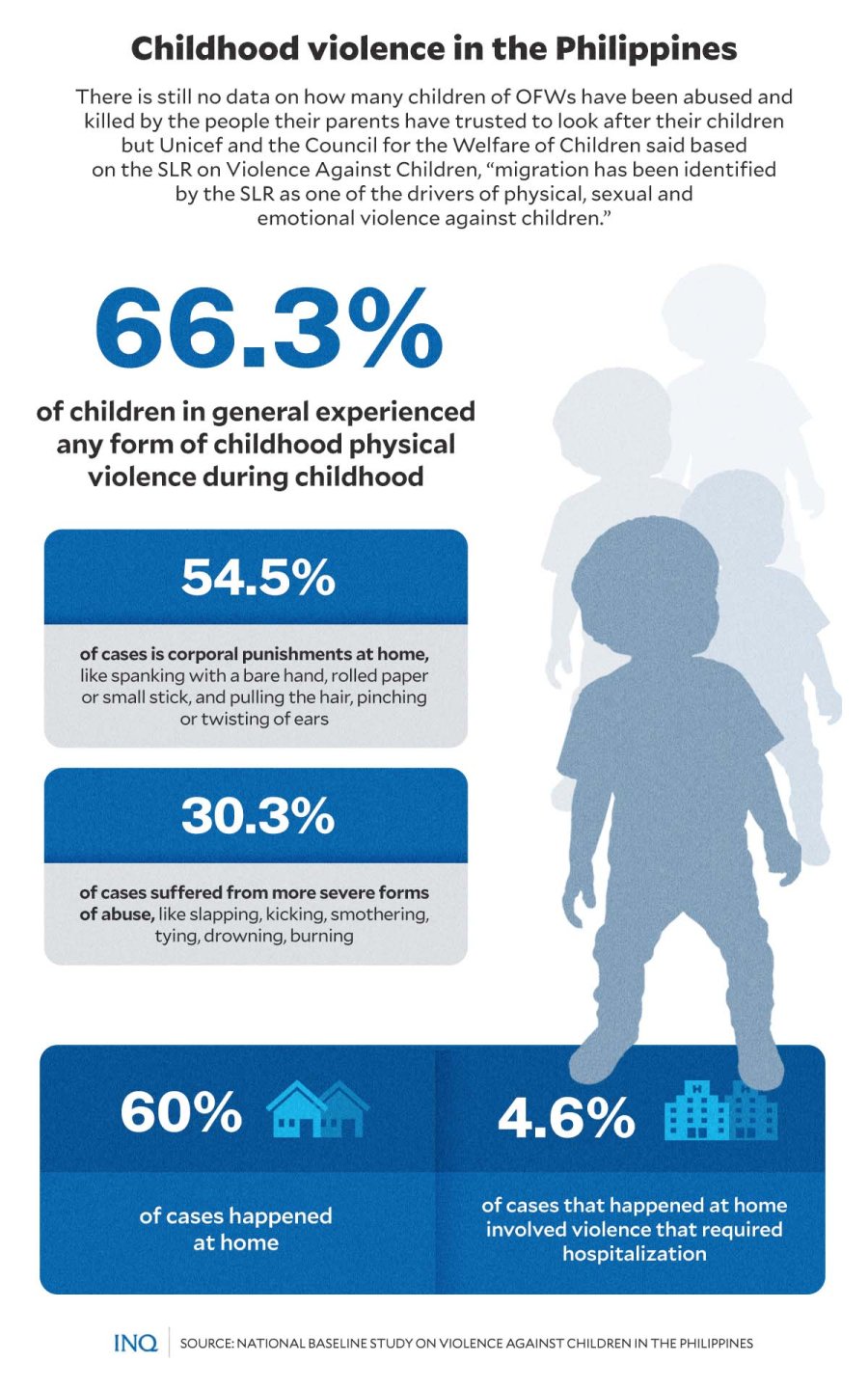

Based on data from the National Baseline Study on Violence Against Children, at least 3 in 5 children aged 13 to 24 years old experienced childhood physical violence in its various forms.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) and the Council for the Welfare of Children (CWC) said 60 percent, or over half of the cases, happened at home and that 4.6 percent were physically abused with injuries that required hospitalization.

Specifically, one in two received corporal punishments at home, like spanking with a bare hand, rolled paper or small stick, and pulling the hair, pinching or twisting of ears, while a third suffered from more severe forms of abuse like slapping, kicking, smothering, tying, drowning, burning.

As stressed by the two agencies, based on the Systematic Literature Review (SLR) on Violence Against Children, “migration has been identified by the SLR as one of the drivers of physical, sexual and emotional violence against children.”

Based on the latest data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), there were 1.83 million OFWs in 2021, which consisted of 96.4 percent with existing work contracts and 3.6 percent without working visa or work permits.

The PSA, sharing the results of the Survey on Overseas Filipinos, said the number of OFWs increased by 3 percent from 1.77 million in 2020, but still below 2.2 million in 2019.

Anxious OFWs

Ople said many of the reasons behind the “anxiety being felt by workers overseas and their families back home have to do with family ties, especially for mothers, who earn from caring for other people’s children.”

She stressed that “they especially need support not only from the government but also civil society groups and even interfaith groups on how their children can be mainstreamed and be better protected.”

Based on data from the PSA, there were more women working overseas, accounting for 60.2 percent, or 1.10 million, in 2021. Male OFWs accounted for only 39.8 percent, or 730,000.

Back in 2020, the PSA said “international labor migration has been a part of Filipino family life,” with the 2018 National Migration Survey (NMS) finding out that 12 percent of Filipino households “had a member who was or had been an OFW.”

The PSA said when the NMS was conducted, nine percent of households had at least one member currently overseas.

The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao was the region with the highest percentage (24 percent) of households with current or former OFW members, followed by Cagayan Valley (22 percent) and the Ilocos Region (18 percent).

It said in contrast, Caraga Region (5 percent), Mimaropa (7 percent) and Central Luzon (7 percent) had the lowest percentage of households with current or former OFW members.

MOU on protecting OFW kids

Back in 2017, the Department of Labor and Employment, through the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA), signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the DSWD and Department of Justice (DOJ) for the provision of full protection to children left behind by OFWs.

“We were quite alarmed by the results of the study on violence against children which stated that migration is one of the reasons of physical, sexual, or psychological violence to children,” said then Labor Secretary Silvestre Bello III, highlighting the study initiated by the CWC and Unicef.

Bello stressed that the MOU is part of the government’s effort to balance the desire of the OFW parents to provide for the needs of their children by working overseas on one hand, and to ensure that their children are in the safe hands of the people they have chosen to look after the wellbeing of their loved ones.

As stated in the agreement, OWWA shall intensify child protection campaigns on violence against children, especially children of OFWs through the immediate clarification and resolution of issues and concerns raised by the OFWs.

It shall also integrate the Child Abuse and Exploitation module prepared by the DSWD in the conduct of trainings and orientations for OFWs and their families, and report suspected cases or incidence of child abuse to DSWD, DOJ and other law enforcement authorities.

The DOJ is expected to conduct preliminary investigation on child abuse and exploitation cases; provide legal advice/assistance to the child/family; coordinate and monitor the status of referred cases filed at the Prosecutors’ Offices and in courts.

It was also expected to ensure child-friendly, child and gender sensitive investigations of cases as stipulated in the DOJ-CSPC Protocol for the Management of Child Victims of Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation; conduct speedy preliminary investigation/resolution of referred cases; and participate in the case conferences on cases referred by OWWA and in convergence programs.

The DSWD shall provide assistance, shelter and protection to children of OFWs who are victims of child abuse and exploitation in coordination with the LGUs; coordinate with the agencies covered by the MOU on the process of reporting complaints and assistance; and participate in the prevention campaign against Child Abuse and Exploitation.