October 26, 2022

MANILA – It was in 1972 when Beth Gaon gave birth, but a few days later, she and her child died because of complications, her relative, Arceli Estioco, said.

As stated by the then Ministry of Health and Philippine Health Statistics, the maternal death rate in 1972 was 1.4 percent, while the newborn death rate was 31.9 percent.

Estioco told INQUIRER.net that Gaon, who did not receive any prenatal check, gave birth at home and was assisted only by hilots—traditional birth attendants.

It was stressed that in 1972, maternal deaths, which were 1.4 per 1,000 live births, accounted for 0.5 percent of all deaths in the Philippines.

Then in 2000, while the maternal death rate saw a decrease—1.0 per 1,000 live births—the Philippines committed to reduce maternal deaths to 55 per 100,000 live births by 2015.

So years later, to meet its Millennium Development Goal, the government passed the Maternal, Newborn and Child Health and Nutrition Strategy.

The said strategy, which was referred to as the “No Home Birth Policy,” mandated local governments to generate income for the improvement of birthing facilities.

This, as home births were considered by the government as the reason for high maternal deaths in the Philippines.

However, as stated by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) in its data regarding “Causes of Deaths in the Philippines,” maternal and newborn deaths are still rising.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

While direct obstetric deaths fell to 1,055 in 2021 from 1,519 in 2020, an increase in maternal deaths was seen in the first six months of 2022 compared to the same period last year.

<strong>READ: <a href="https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1683444/psa-logs-higher-infant-mortality-rates-popcom-says-its-due-to-lack-of-healthcare-access#ixzz7iiVhjqQQ">PSA logs higher infant mortality rate; Popcom says it’s due to lack of healthcare access</a></strong>

Direct obstetric deaths, or direct maternal deaths, are those resulting from obstetric complications of the pregnant state, and from interventions, omissions, or wrong treatment.

Based on data from the PSA, the deaths classified as such increased to 468 in January to June 2022 from 425 in January to June 2021.

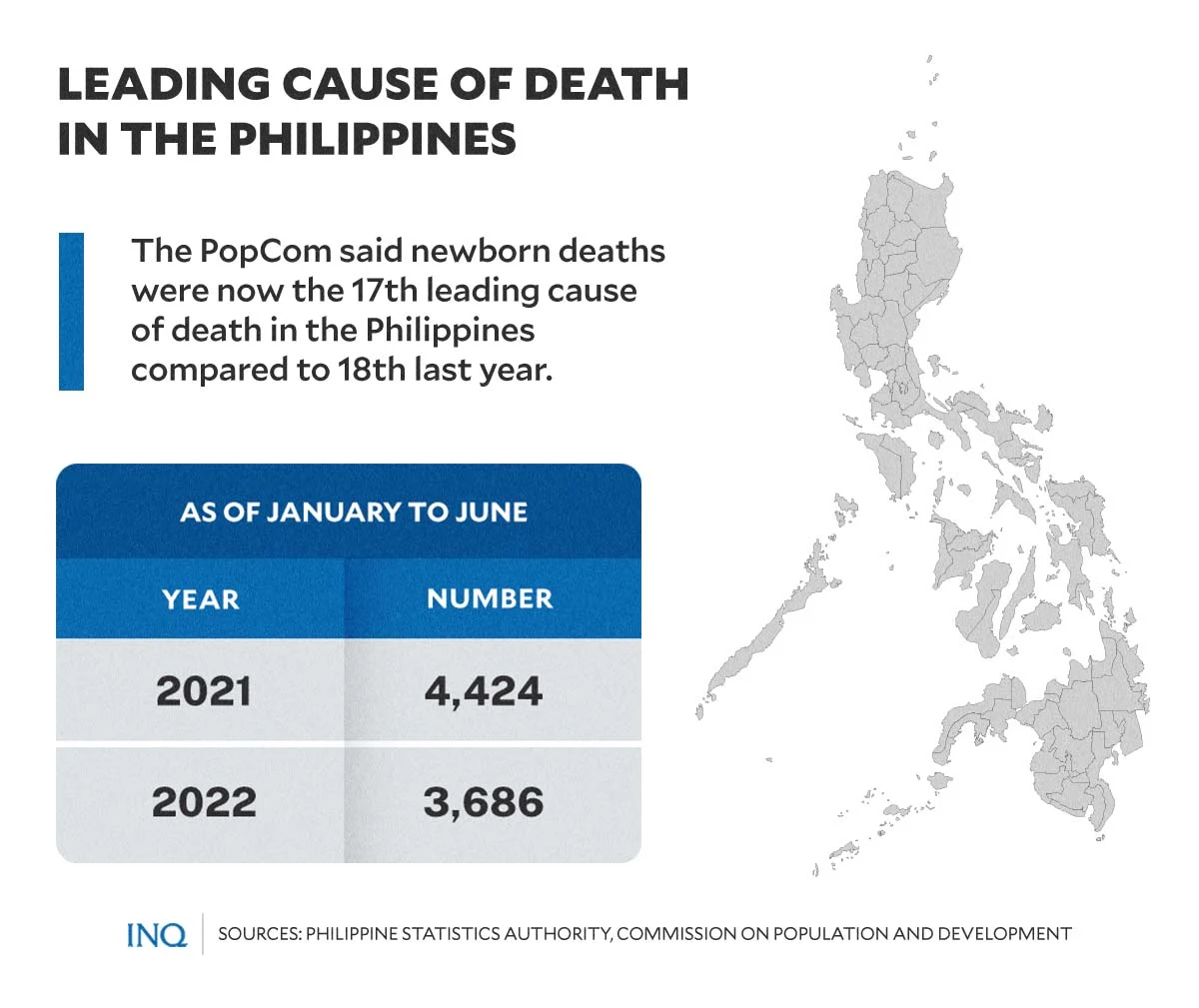

Likewise, the Commission on Population and Development (PopCom) said newborn deaths were lower in the first six months of 2022 (3,686) compared to the same period in 2021 (4,424).

However, it said newborn deaths, or deaths caused by certain conditions originating in the perinatal period, is now the 17th leading cause of death in the Philippines, higher compared to 18th last year.

So should the government say that home birth is still the problem?

Lack of access

No less than PopCom executive director Lolito Tacardon said “reasons [for this] could be the delay in referral, and in general, the quality of the services being provided in the health facility.”

He told ANC that “if we have to assess the overall situation, it points to the overall quality of the health care system.”

Tacardon, however, stressed that “we do not have solid evidence yet as to the particular aspect of the overall quality of health care being provided in our facilities.”

But PopCom said one thing is clear: “The increasing rate of their mortalities in the past two years has been indicative of the difficulties in obtaining services related to maternal and newborn health.”

This, it said, “have produced fatal consequences” and is now prompting the government to provide enough medical attention to mothers and their newborns, especially in the latter’s first 1,000 days of their lives.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

As stated by Tacardon, “this condition indicates an issue in accessing appropriate, quality and timely services from health care facilities.”

While he stressed that “we also have to investigate whether the increase in deaths were caused by home births,” the rise in deaths “poses a challenge to improve our local health system for emergency obstetric and newborn care,” which was definitely affected by the COVID-19 crisis.

“Our health system should now be slowly recovering from the deluge of cases caused by the pandemic to ensure adequate services for other health concerns such as those related to maternal, infant and child health,” he said.

Deadly poverty

Based on data from the 2017 National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), more than half of 15 to 49-year-old women have at least one problem in accessing health care, and the most common at 45 percent was “getting money for treatment.”

Younger women, who are 15 to 19 years old (64 percent), women with no education (76 percent), and women from the poorest households (72 percent) are more likely than the other women to report problems in accessing health care for themselves.

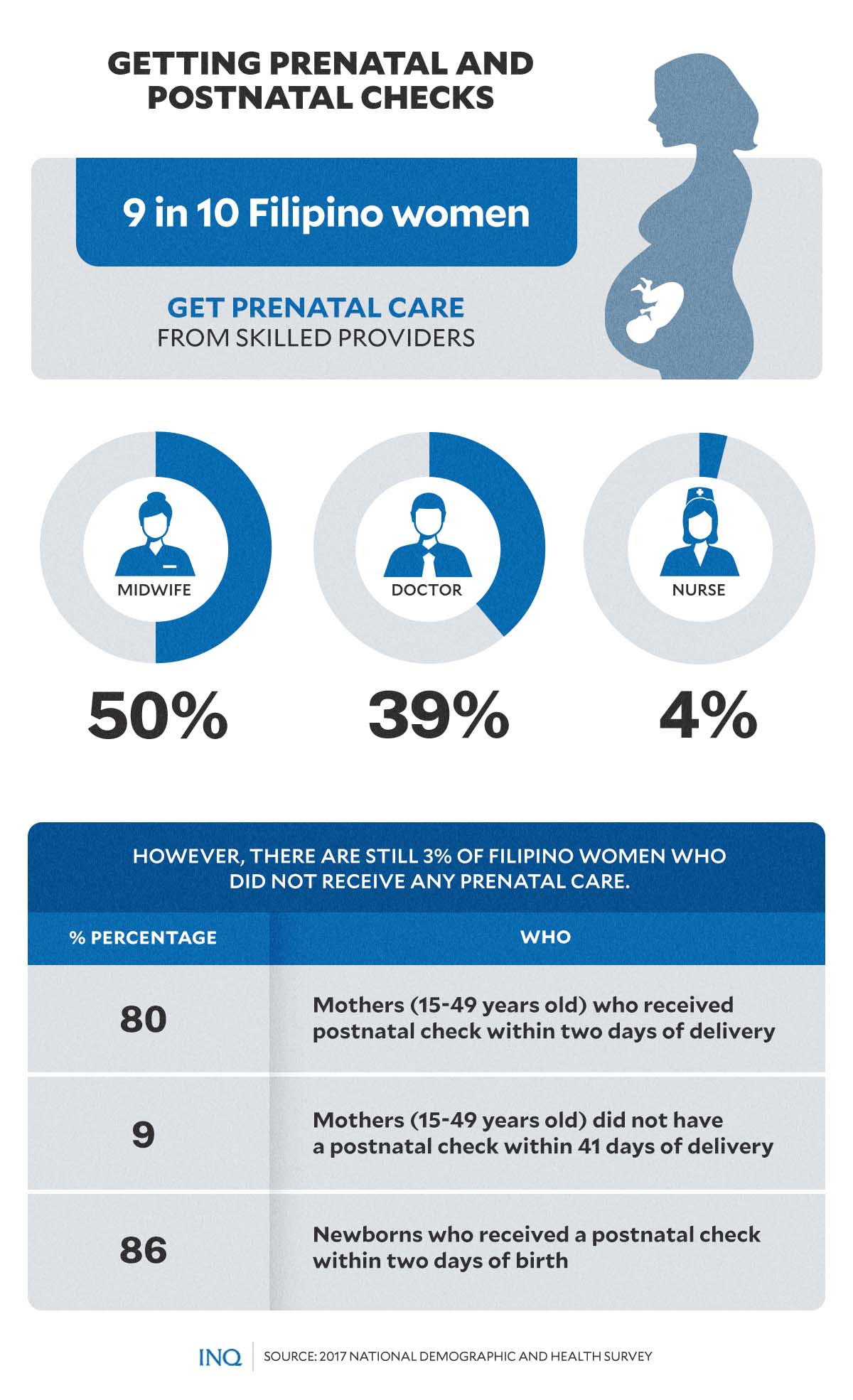

As stated in the NDHS, nine in 10 Filipino women received prenatal care from a skilled provider such as a midwife (50 percent), doctor (39 percent), or nurse (4 percent).

However, three percent of women received no prenatal care at all.

It was likewise learned that women with higher levels of education and those from the wealthiest households are most likely to receive prenatal care from a skilled provider.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The NDHS stated that seven in 10 women had their first prenatal visit in the first trimester, as recommended. Eighty-seven percent of women make four or more prenatal visits.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

As stressed by the Department of Health, there should be at least four prenatal checks—at least one in the first three months; at least one in the fourth to sixth months; and at least two in the seventh to ninth months.

The World Health Organization said if a mother goes for regular prenatal care, gives birth in a health facility and is assisted during birthing by a skilled-birth attendant, there is a lower risk of mortality for that mother and her newborn baby.

Inequality in access to services

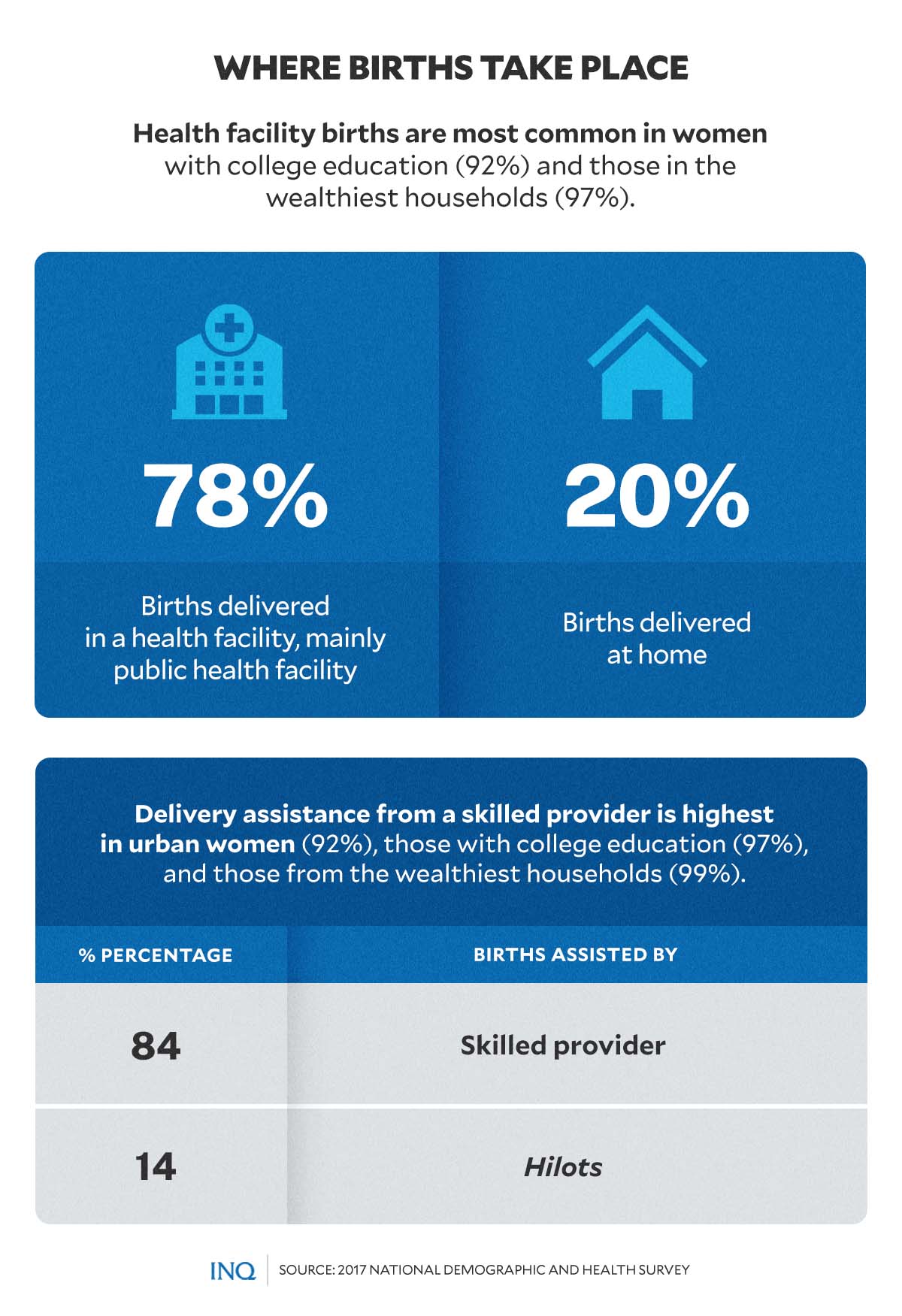

More than three in four births (78 percent) were delivered in a health facility, mainly in public health facilities, the NDHS learned, while one in five births were delivered at home.

Health facility births were most common in women with college education (92 percent) and those in the wealthiest households (97 percent). Health facility deliveries have nearly tripled, from 28 percent in 1993 to 78 percent in 2017.

Overall, 84 percent of births were assisted by a skilled provider, mostly by doctors, while 14 percent were assisted by hilots.

The NDHS found that delivery assistance from a skilled provider was highest in urban women (92 percent), those with college education (97 percent), and those from the wealthiest households (99 percent).

Postnatal care helps prevent complications after childbirth, it stated, however, nine percent did not have a postnatal check within 41 days of delivery.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

This, even if more than 80 percent of mothers (15 to 49 years old) received a postnatal check within two days of delivery. Eighty-six percent of newborns received a postnatal check within two days of birth.

As stated by Karlo Paredes in his study, “Inequality in the use of maternal and child health services in the Philippines,” inequality in the use of maternal and child health services had limited pro-poor improvements.

“Household income remains to be the major driver of inequities in maternal and child health services use in the Philippines.”

Tacardon stressed that this problem now “calls for the full and intensified implementation of the Universal Health Care Law, as well as the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Law, which mandate the upholding of the well-being and overall health of Filipino moms and their young children.”