October 28, 2025

JAKARTA – In a modern democracy, no institution, secular or religious, should be exempt from public scrutiny.

If anything, such scrutiny is a must if the institution in question gets funding from the state or receives a permit from the government to run their operation.

The degree of oversight should in fact be greater if such an institution handles the dispensing of basic services such as health care and education.

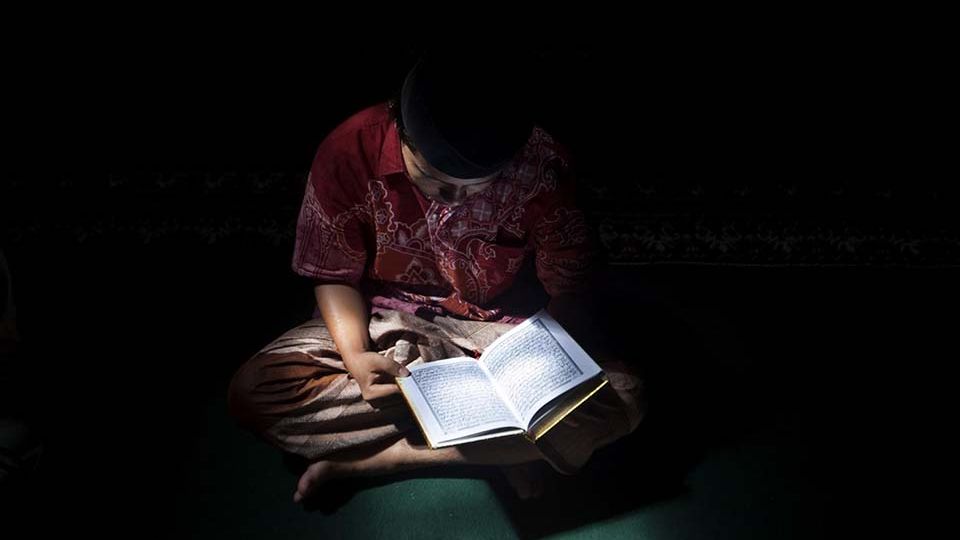

Pesantren (Islamic boarding schools), are such an institution. In fact, in Indonesia, Islamic boarding schools are an institution in the truest sense of the word.

Long before the birth of the modern nation-state of Indonesia, these traditional Islamic boarding schools were the only way for common people, especially in the country’s rural regions, to get access to education.

The Dutch colonial government never had any intention to provide education for the masses before the late 19th century, so for most people, going to these traditional schools was the only way for them to get a basic education.

Even after Indonesia gained independence, these traditional schools continued to play a major role in education as the new nation’s bureaucracy could not build a modern infrastructure for education fast enough.

Yet as the nation modernized, some features from the pesantren’s feudal past remained.

Religious leaders have always been key players in Indonesian society and nothing illustrates the situation better than the relationship between citizens, especially in rural areas, with local Muslim preachers, known as kyai, who in most cases also serves as leaders of Islamic boarding schools.

Leaders of these Islamic boarding schools are sources not only of religious authority but also political authority who win deference from their followers.

By agreeing to send their children to get their education in an Islamic boarding school, parents give free rein for the school’s administrators to do anything.

From the recent collapse of a building operated by Al Khoziny Islamic Boarding School in East Java, we know that some of the students were involved in construction work to open a new floor at the popular school.

Some parents whose children survived the collapse told stories that their loved ones could have perished if they were not on a break when the accident happened. (But some parents of those who died in the accident took comfort from the notion that they were martyred).

And then, there is of course the problem of abuses of power committed by teachers, administrators or leaders of these religious institutions.

The Research Center for Islam and Society (PPIM), a think tank affiliated with the State Islamic University (UIN) in Jakarta estimated that more than 43,000 students at Islamic boarding schools are vulnerable to sexual abuse.

It was these problems that journalists at the Trans7 television channel tried to highlight in its program Xpose Uncensored in early October. The episode, which aired on Oct. 13, highlighted the common practice of paying excessive deference to one well-regarded leader of Lirboyo boarding school in East Java.

The backlash was swift. Protesters, mostly members of the country’s largest Muslim organization Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), staged a week-long protest in front of Trans7 headquarters, during which one of their leaders called for the murder of journalist involved in the production of the program.

Due to pressure from these protesters, the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) issued an order for Trans7 to take the program off the air and apologize to the leaders of Lirboyo.

The protesters certainly think that the move was to protect the honor of religious leaders, but it has set a dangerous precedent for free speech in the country.

As the law now stands, the citizen of this country still have the right to criticize the President. But why would we exempt these religious leaders from scrutiny?