April 21, 2023

TOKYO – The “2024 problem” is looming over the logistics industry. Regulations to limit overtime for truck drivers will be introduced in April 2024, which could greatly reduce their ability to transport goods.

Concern has grown over whether logistics networks for home delivery, and those connecting manufacturing to retail businesses, can be maintained under the new regulations. Urgent measures are needed to prevent a negative impact on people’s lives and the economy.

“We’re trying to hire drivers by offering higher wages, but we can’t recruit people. If we’re still in this situation when 2024 comes, our company may not be able to continue operations,” said a 49-year-old manager at a transportation company in Saitama Prefecture.

Currently, truck drivers are not subject to limits on overtime. However, new labor standards based on the Law on the Arrangement of Related Laws to Promote Work Style Reform will be introduced in April 2024, capping truck drivers’ overtime at 960 hours per year.

About 30% of the companies that responded to a survey by the Japan Trucking Association had drivers with annual overtime of more than 960 hours. This figure grows to about half when looking only at long-distance transport.

This means many truck drivers work more than 80 hours of overtime each month, the “karoshi line” threshold for increased risk of death by overwork.

After the new regulations are introduced, the amount of cargo that can be transported is expected to decrease because drivers can not work as many hours. A government expert panel has estimated that unless countermeasures are implemented, freight transport capacity will be 14.2%, or 400 million tons, less than the fiscal 2019 level.

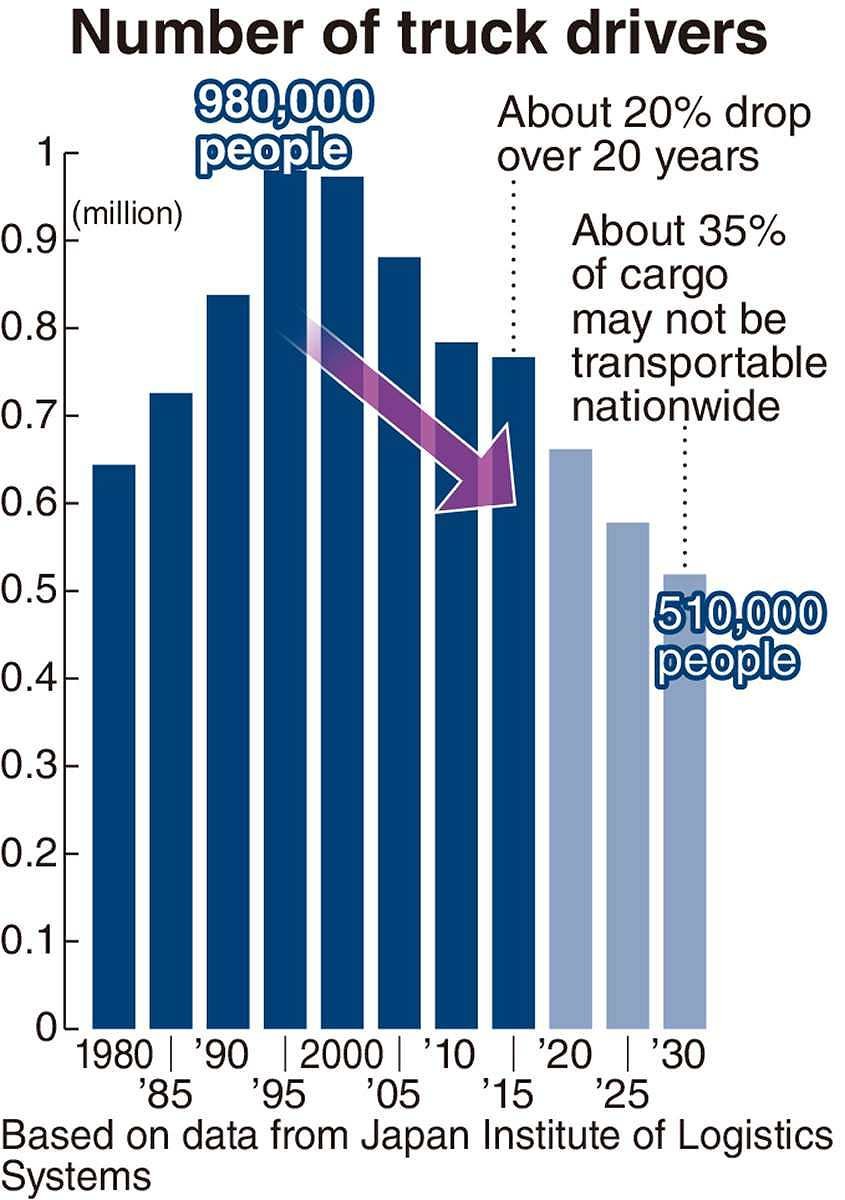

In January, Nomura Research Institute, Ltd. released an estimate that about 35% of the nation’s cargo would be unable to be transported in 2030. The Tohoku and Shikoku regions saw their figures top 40%, raising concerns that the impact will be particularly serious in rural areas.

Low wages

Long working hours and low wages have become the norm in the transportation industry.

According to a survey by the Health, Labor, and Welfare Ministry, heavy-duty truck drivers worked an average of 212 hours monthly, and medium- and light truck drivers worked 207. These figures are about 20% higher than the average of 175 hours for all industries.

In addition to driving, truck drivers must perform such tasks as loading and unloading cargo. They also often have to wait long hours to suit the convenience of shippers, making it difficult for them to raise productivity.

The average annual wage of heavy-duty truck drivers is ¥4.63 million, or ¥260,000 lower than the average for workers in all industries. Truck drivers’ pay used to be considered high, leading to the saying, “You can build a house if you drive a truck for three years.”

However, the industry was deregulated in 1990, paving the way for the entry of small and midsize businesses. This brought about excessive competition in the industry. As of February this year, the ratio of job openings to applicants for truck drivers stood at 2.26 times, nearly double the average for all occupations. There is clearly a chronic shortage of drivers.

Because the working environment for truck drivers has not improved, the number of young staff remains low. According to the Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry, 10.1% of the people working in the road cargo transportation industry are below 30, which is 6.5 percentage points lower than the 16.6% for all industries.

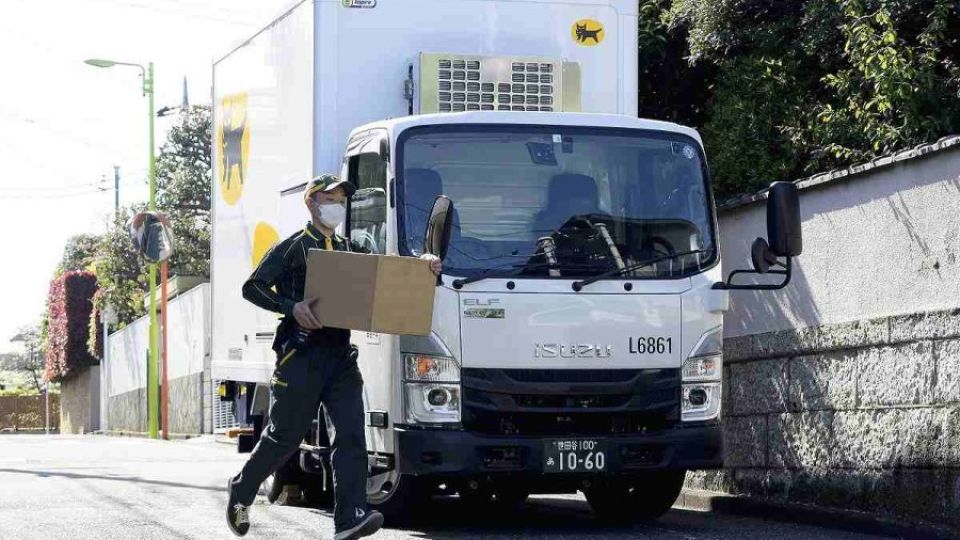

The Yomiuri Shimbun

In contrast, demand for logistics remains high, especially for home deliveries. Mail-order sales grew on the back of higher demand among people staying home amid the coronavirus pandemic, and the number of units for home delivery reached 4.78 billion in fiscal 2020, up about 500 million from the previous fiscal year.

Unless the structural strain on the industry is resolved, the crisis in logistics networks is likely to continue.

“Both companies and consumers have no choice but to accept rising logistics costs,” said Masahiko Harada, a chief researcher of Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting Co. “It’s important to visualize shipping costs and make consumers aware that shipping is not free.”