January 31, 2023

MANILA, Philippines — Teenage pregnancies in the Philippines are so prevalent that last year, a high school teacher in Aklan had to babysit the 9-month-old child of his Grade 9 student.

Neme Guanco had said he felt that he had to help her, especially because he had seen how his student, who was bringing her infant to school every day, was struggling in handling her responsibilities as a student and a mother—all at the same time.

A teacher at the New Washington National Comprehensive High School, Guanco said that “most of the time, she (student) is having a hard time writing and listening […] as she needs to attend to her child’s needs.”

The story of Guanco’s student is indeed a reflection of the condition of young Filipino women who are confronting pregnancy at an early age in the Philippines, where one in 10 live births are to women who are 10 to 19 years old.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNPF), back in 2019, said the Philippines has one of the highest teenage pregnancy rates among ASEAN member states, with over 500 teens becoming pregnant and giving birth every day.

But almost two years since the prevention of teenage pregnancies had been declared a “national priority,” results of studies lead to this conclusion—cases are already declining.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

As stated by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) in its 2022 National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), teenage pregnancies among Filipino women—15 to 19 years old—fell from 8.6 percent in 2017 to 5.4 percent in 2022.

This is consistent with the findings of the University of the Philippines Population Institute’s 2021 Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality Study (YAFS5), which revealed that childbearing among young Filipino women declined from 13.7 percent in 2013 to 6.8 percent in 2021.

Based on the latest PSA data, out of 27,821 respondents, 5.4 percent have been pregnant in 2022—about 1.6 percent of them are currently pregnant while 0.4 percent have had a pregnancy loss.

It stated that out of the percentage of young women who have been pregnant as of last year, most were 19 years old (13.3 percent), 18 years old (5.9 percent), and 17 years old (5.6 percent).

“As expected,” the PSA said, only 1.7 percent of the pregnancies happened among women who were 16 years old, lower than the 3.7 percent in 2017. Some 1.4 percent happened among 15-year-olds, slightly higher compared to 0.5 percent in the previous NDHS.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

These findings came almost two years after Executive Order (EO) No. 141, which was signed on June 25, 2021, had been issued to stress the need to implement mechanisms to address the rising number of teenage pregnancies.

It read that the State shall mobilize existing coordinative and legal mechanisms related to the prevention of teenage pregnancies and to strengthen young women’s capacity to make independent and informed decisions about their reproductive and sexual health.

This, as erstwhile President Rodrigo Duterte stressed that the government recognizes the main reasons for teenage pregnancies, which the Commission on Population and Development (PopCom) said is causing P33 billion in economic losses.

Rooted in poverty, inequality

According to Plan International, an organization that advances children’s rights and equality for girls, teenage pregnancies are being confronted all over the world, but most happen in “poorer and marginalized” communities.

It said this as it considered lack of information about sexual and reproductive health, and inadequate access to services dedicated to young people as some of the reasons there are cases of teenage pregnancies.

The rest are social pressure to marry, sexual violence, child, early and forced marriage, and lack of education, stressing that young women who have received minimal education are five times more likely to bear a child at an early age.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

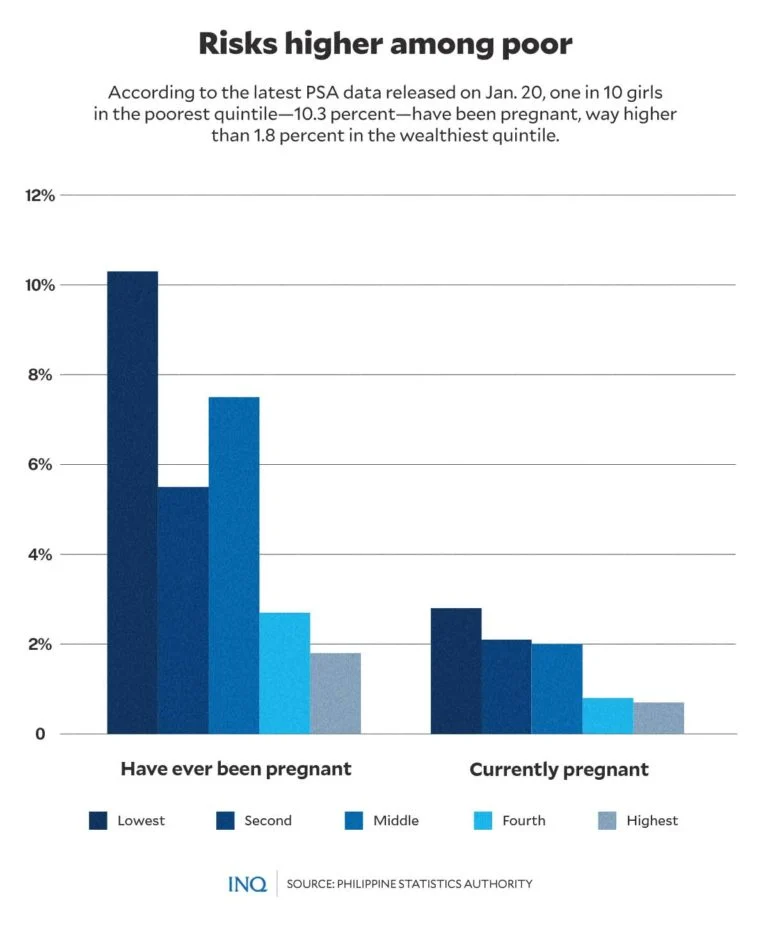

Based on the latest PSA data, which was released on Jan. 20, one in 10 young women in the poorest quintile—10.3 percent—have been pregnant, way higher compared to 1.8 percent in the wealthiest quintile.

“The percentage of teen women who have ever been pregnant decreases with increasing wealth quintile.”

The PSA said out of the young women who are currently pregnant, the trend is also decreasing from poorest to wealthiest—2.8 percent of young women in the poorest quintile then down to 0.7 percent in the wealthiest quintile.

When it comes to educational attainment, teenage pregnancies were most common at 19.1 percent among young women with primary education, or those who completed Grades 1 to 6, the PSA said.

However, “[it] decreases as educational attainment increases, that is, 5.3 percent among those who completed grade levels 7 to 10, 4.3 percent among those with completed grade levels 11 to 12, and 1.9 percent for those who attained college level.”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The World Health Organization said studies related to teenage pregnancies in low- and middle-income countries indicate that levels, especially of risks, tend to be higher among those with less education or of low economic status.

Economic, social consequences

When PopCom asked Malacañang to declare the issue a “national emergency,” it stressed that teenage pregnancies “affects the very essence of the country’s development, because the state of young people today will affect the state of our collective future.”

As stressed by Oxfam, an anti-poverty organization, “poverty is a common thread among many young Filipino mothers,” saying that in 2020, 57 percent of those in their teenage years were part of the poorest 40 percent of the population.

The National Nutrition Council (NCC) said early childbearing may result in poor health outcomes and may be a threat to the country’s economic growth as pregnant teenagers “are less likely to complete higher education.”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

Because of this, the PSA said they may have “lesser ability to earn more income over the course of a lifetime, causing economic losses to the country,” P33 billion to be exact.

However, the National Economic and Development Authority had said the economic cost for teenagers who got pregnant is staggering, placing between P24 billion and P42 billion the lifetime income they had lost to early childbearing.

The latest PSA data indicated that by area of residence, the percentage of young women who have been pregnant was slightly lower in urban areas (4.8 percent) than in rural areas (6.1 percent).

Across regions, Northern Mindanao had the highest percentage at 10.9 percent. Next to it were Davao Region (8.2 percent), Central Luzon (8 percent), and Caraga Region (7.7 percent).

The PSA said the lowest percentage of teenage pregnancies was reported in Ilocos Region (2.4 percent), Bicol Region (2.4 percent), Metro Manila (2.8 percent), and Soccsksargen (3.8 percent).

As stressed by the NCC, teenage pregnancies are also associated with a higher risk of health problems such as preeclampsia, anemia, sexually transmitted diseases, premature delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, and poor mental health outcomes.

Artificial decline?

It was last year when PopCom first noted the decline in teenage pregnancies in the Philippines, so now that the PSA released its new findings that cases, indeed, dropped last year, is the end to the problem already in sight?

No one can tell.

However, PopCom was clear that vigilance is still needed, especially now that most COVID-19 restrictions had already been lifted. To recall, the commission said the lockdowns had ensured limited physical contact among youth since 2020.

PopCom officer-in-charge and executive director Lolito Tacardon had said the COVID-19 crisis presented new circumstances that forced young people to spend months inside their homes with their movements outside restricted by lockdowns.

This was also the reason that Rom Dongeto, executive director of the Philippine Legislators’ Committee on Population and Development, told GMA News that the decline in teenage pregnancies could be “artificial.”

Based on the findings of the YAFS5, fewer young Filipinos are having sex before marriage as of 2021, with only 22 percent of the respondents saying they had premarital sex.

The researchers said they had seen a consistent rise in the number of 15- to 24-year-olds engaging in premarital sex from 18 percent in 1994 to 23 percent in 2002 and 32 percent in 2013.

However, the trend stopped in 2021, when the COVID-19 crisis prompted the government to impose lockdowns and halt the physical conduct of classes in all year levels.

Deeper understanding needed

Tacardon, last year, said “the notable decline in the proportion of young women who have started childbearing can be considered a result of the continuing and collective efforts, as well as initiatives, of all stakeholders from the national levels down to the local levels.”

He stressed that institutions, especially the government, should put in place mechanisms to enforce EO No. 141, which directed all agencies to identify interventions to stem the rise in teenage pregnancies.

But the findings of one of Oxfam’s latest studies on the issue stressed that “perhaps [the] government and civil society should rethink their approaches to teenage pregnancy.”

“It’s not enough to say that teenage pregnancy is bad. It has to align with their desire, especially since there are some people who want to get pregnant at a young age,” said Sabrina Gacad, the author of the study.

“Maybe we don’t need to change their desire for pregnancy but instead their idea of fulfillment as a woman.”

Gacad said teenagers should also be guided to see that there are other ways for women to be accomplished or be fulfilled. “Broadening that option for young women might change fertility preferences.”

This, as the study revealed that there is an “overwhelming acceptance of pregnancy among young women who had experienced it.” Their reasons ranged from seeing it as a blessing to simply accepting it because it had already happened.

“Pregnancy acceptability has more to do with ideas and expectations about motherhood, and the desire to make the most out of an unpleasant situation, than the circumstances around their sexual initiation,” Gacad said.

The respondents gave various reasons for their early sexual initiation, ranging from being forced or coerced to “eventually” wanting it. Early sex and teenage pregnancies often occur amid the desire of male partners to have sex and start a family.

“Power dynamics are skewed against teen girls or young women when their partners are older and employ a combination of coercive or abusive tactics,” Gacad said, stressing that abstinence worked only for partners who were of the same age.

“Because if you are of the same age, you have the same environment, a young person can assert their desires against a possibly assertive male partner […] What is worrying is how long women can keep saying no and their wishes are respected by their partner.”

This was the reason that Gacad and Oxfam stressed the need for institutions, public and private, to come up with ways to support young women in the Philippines facing such conditions.

“Without a clear and comprehensive vocabulary for their pleasures and their needs, adolescent girls and young women are unable to express consent and enforce their refusal.”

“In taking an unexpected pregnancy to term, and in raising children, they limit their social or economic opportunities, while being expected to be good mothers who will put the well-being of their children above anything else,” she said.

New ways needed

Nathalie Verceles, of the UP Center for Women’s and Gender Studies, had said Gacad’s study shed light on “the various structural constraints that pregnant young women contend with” and how young women, no matter how limited their power is, “make the best of what would normatively be considered an unfortunate situation.”

“Teenage pregnancy is a problem also because of society’s persistently puritanical views on sex. We refuse to acknowledge that adolescents have sexual rights, and insist that they should not be engaging in sex.”

“[But] the reality is that they are engaging in sex, and the lack of access to quality sexual and reproductive health services will not hinder or stop them,” Verceles pointed out.

Because of this, Verceles said teenage girls should “have a right to sexual and reproductive health and rights information and services, which will protect them not only from early pregnancies and STDs, but also unsafe abortions.”

Gacad, meanwhile, said there should also be a change in perspective among groups trying to address the issue.

“You cannot stop pregnancies just by insisting on contraceptives uses,” she said. “If we wanted young people to take contraceptives, we must discuss why they would need to in the first place, which means discussing their curiosity about or desire for sexual intimacy.”

It was stressed that there is much to be done to “help young people turn their pleasure into greater power,” saying that it does not help that society refuses to accommodate teen sexuality, attraction, pleasure and desire.

“For this power to grow, the undesirability of teen sexuality should be eliminated and the choice of teenagers to carry their pregnancies to term or prevent them completely must be met with material, health, and psycho-social support from loved ones and the public health and social welfare institutions.”