July 2, 2025

SEOUL – Twenty-eight-year-old Kim goes on a five-hour trip to Ulsan, or any other region, as soon as she gets off work on a weekday. Not for sightseeing or to visit friends, but for property viewing.

“I finish work at 6 p.m. then head to Seoul Station to go for ‘imjang’ — a Korean term for site visit or field research on real estate properties — in different regions,” she told The Korea Herald.

But she’s not looking for a home to live in — she’s looking to invest.

Over the past two years, Kim has spent 10 million won (about $7,400) on investment courses. What she learned was simple, if sobering: With her current income, saving will never buy her a home. Investing is her only option.

Among her preferred strategies is a method known as “gap investment,” which leverages Korea’s unique “jeonse” lease system. Under a jeonse lease, tenants pay a lump-sum deposit, often 60 to 80 percent of the home’s value, instead of monthly rent. Landlords hold the deposit during the lease, usually to earn interest from a bank, and return it in full at the end of the contract.

For investors, this opens a door: Buy a property by paying only the difference, or “gap,” between the property’s market price and the jeonse deposit.

For example, if an apartment is worth 1.7 billion won and a jeonse deposit of 1 billion won already in place, the investor only needs 700 million won to acquire ownership, either in cash or with a loan.

Through this approach, Kim now owns two apartments in Ulsan worth 600 million won, having put up only 100 million won of her own money.

To acquire what she has now, Kim has spent every weekend walking over 20 kilometers each day to study neighborhoods — their environments, schools, and proximity to public transportation and other facilities — all the elements that factor into buying a house.

“Using all my free time to study and go for imjang is exhausting. I’m sacrificing my youth so I won’t suffer in old age,” Kim said. “And to have that stable life is absolutely impossible with my current salary,” she said.

“I earn 4 million won a month, and the apartments in Seoul cost over 2 billion. Even if I didn’t spend a penny of my salary and saved it all, it would take over 40 years to buy a house, which by then would be much more expensive.”

Strategic sacrifice

Kim is not alone. A growing number of young South Koreans are turning to aggressive investment tactics, seeking financial stability in the face of an uncertain future.

“This is hard to believe. We used to start property investment in our 40s and 50s. But now I’m taking an investment course with a 25-year-old,” said a 45-year-old surnamed Chae.

Informal “imjang crews” now walk neighborhoods together, sharing information and strategies. This rise in financial self-discipline is extends beyond courses and walking tours. Social media is fueling the trend.

The number of Instagram posts with the Korean hashtag “investment” is over 2.3 million, along with property-related investment posts amounting to over 1.6 million.

The online platform where Kim learned her skills, Weolbu — short for “salaried and rich” — has ballooned to over 1.5 million users in less than 18 months — 10 times its size in 2023. The company’s profits more than doubled, from 18.3 billion won in 2022 to 50.8 billion won in 2024.

“Becoming a financially secure salaried worker is my dream,” said 30-year-old Choi Hyun-sik, who is currently enrolled in an investment course. “I want to use my salary as a baseline and earn more through smart investments so I can afford a house and prepare for retirement.”

Aptrashu, a popular Instagram influencer who focuses on providing real estate investment strategies, particularly gap investment, has amassed over 70,000 followers — 80 percent of them in their 20s and 30s.

“I started this Instagram to help those in their 20s and 30s who don’t have much money to put toward buying an apartment in Seoul but still want to grab this kind of opportunity,” he told The Korea Herald.

“Imjang” class participants, led by Instagram property investment influencer Aptrashu, walk together near Godeok Station in Gangdong-gu, eastern Seoul. PHOTO: APTRASHU/THE KOREA HERALD

Aptrashu attributes the current investment craze to the fear young Koreans experienced as the COVID-19 pandemic roiled the economy.

“In 2021, there was a surge in real estate prices in South Korea. Due to COVID-19, the government released a lot of funds for small businesses and those who lost their jobs. With the added liquidity, the value (of money) dropped and housing prices skyrocketed. The government put restrictions in place to contain the sudden rise, but people flocked to apartments that did not have restrictions, which led to demand soaring in those areas, and in turn to higher prices,” he explained.

The psychological effect, he noted, was profound. “Many in my generation felt an urgency: If we don’t act now, we’ll never catch up.”

“When the price of apartments soared, many people thought they would never be able to buy a house in their lifetimes. The sudden gap between those who own a house and those who don’t widened, and many young people began to think they had to prepare for the future fast,” he explained.

And it’s not just any house people want to own — it’s an apartment in Seoul, he added. For many, owning an apartment in Seoul is a symbol of success and security, an ultimate life goal in South Korean society.

“Seoul apartments carry enormous symbolic weight,” said Aptrashu. “They aren’t just a place to live. They’re a milestone — something that proves you’ve made it.”

Unlike speculative cryptocurrency frenzies or meme stock booms, this investment behavior is deeply rooted in structural fear — particularly about aging.

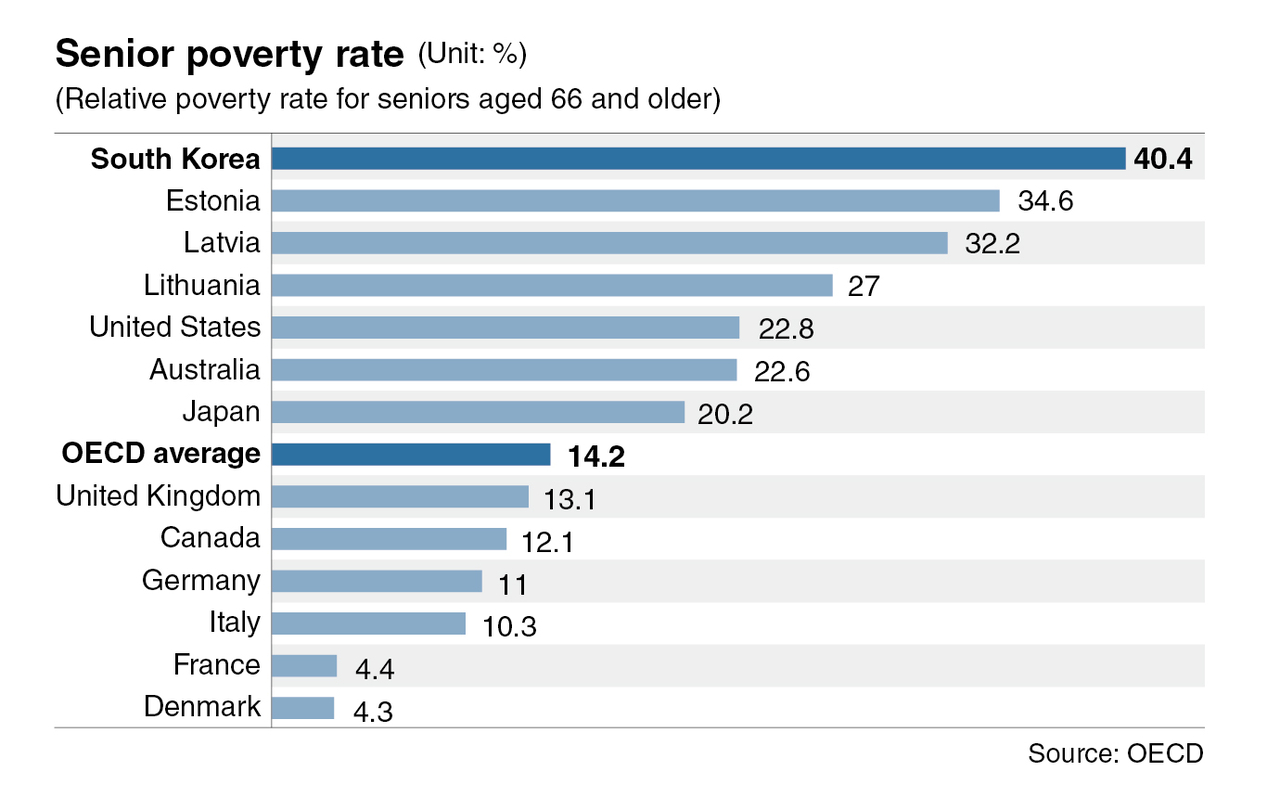

Graph showing senior poverty rate by countries of OECD. SOURCE: OECD; GRAPHICS: THE KOREA HERALD

Anxious about the future

Many young Koreans are more scared than ever about their future.

“Thinking about getting old, I get depressed. What would happen if I can’t buy a home on my current salary? How can I have children and raise them? How will I take care of myself in the future with the pension crisis we face right now?” said a 28-year-old surnamed Choi, who works at a major conglomerate.

South Korea has one of the world’s highest rates of elderly poverty among advanced economies. According to the OECD, 40.4 percent of South Koreans aged 66 and over lived in relative poverty as of 2020 — defined as earning less than half the national median income. That’s nearly three times the OECD average and significantly higher than comparable countries: Japan (20.2 percent), the US (22.8 percent), and Estonia (34.6 percent).

For many young South Koreans, this is a harrowing glimpse of their own future.

“The fear is real,” said Professor Yoon In-jin, a sociologist at Korea University. He attributes the young Koreans’ desperation to invest to structural and generational change.

“From a social structural perspective, from the 1960s to the 1990s, Korea was in the era of constant growth. So young people at that time were focused more on bigger causes like community, society and the nation. As they witnessed their lives getting better, they didn’t fear what the future would bring,” Yoon explained.

Yoon added that the phenomenon is the result of a unique feature of this generation.

“Young people today are more realistic, more individualistic. They know the economy isn’t growing like it did in the past. They doubt pensions will still be solvent when they retire. They can’t rely on the government or the system. So they turn to property.”

Yoon points to a shift in generational values. “Their parents lived through high-growth decades. They (parents) believed that if you worked hard and saved, you’d be okay. That belief doesn’t hold anymore. Today’s young adults were raised in smaller families, often as only children, and they’ve grown up with strong parental support — but in a society that’s no longer economically expanding.”

This inward focus, while understandable, carries risks.

“I worry about where this hyper-individualism could lead,” Yoon said. “As young people focus on their own success, they sometimes end up with a growing hostility toward social minorities, such as immigrants, people with disabilities, women and lower-income groups,” Yoon said.

Though starting one’s interest in finance and investment is crucial and is good for the economy, he said, that way of twisting individualism into resentment toward minorities is something to be cautious about.