October 6, 2025

TOKYO – This autumn marks 20 years since the beginning of an effort to release artificially bred oriental white storks — called konotori in Japanese — back into the wild in Toyooka, Hyogo Prefecture.

The animal’s breeding grounds have since expanded to 13 prefectures including Ibaraki, Kyoto and Saga, with the population in the wild growing to 558 as of late August.

The project to reintroduce the “bearers of happiness,” which were once extinct in Japan, is still halfway to completion, but hopes are high for continued population growth and habitat expansion.

In late June, four chicks fledged from an artificial nest on a tower facing Lake Kasumigaura in Namegata, Ibaraki Prefecture. It was the third consecutive year of successful natural breeding in the city.

Oriental white storks typically migrate to areas rich in fish, frogs, insects and other prey.

“The chicks perhaps took a liking to the abundant natural environment of Lake Kasumigaura and surrounding areas,” a city official said.

The large migratory bird, which is a Special Natural Monument, has a wingspan of about 2 meters. Artificial breeding and reintroduction programs were implemented across the country after the species became extinct in Japan in 1971. The species is classified as Threatened IA (Critically Endangered) on the Environment Ministry’s Red List, indicating an extremely high risk of extinction.

Konotori had inhabited various regions in the country until the early Meiji era (1868-1912). However, the population rapidly declined due to habitat degradation, overhunting, pesticides and a lack of food. The last wild individual in Japan died in Toyooka in 1971, marking the species’ extinction.

Hyogo Prefecture and Toyooka City launched the reintroduction project in 1992. The initiative was sparked seven years earlier when six juvenile storks were adopted from the former Soviet Union. Breeding and rearing continued at the Hyogo Park of the Oriental White Stork with the goal of “returning extinct storks to Japan’s skies.”

The birds were first reintroduced to the wild on Sept. 24, 2005. Five birds were selected from a breeding population of over 100 as the first step toward reintroduction. Each was fitted with a radio transmitter on its back to track how far they flew and where they settled.

The project team used the data from the transmitters to understand the birds’ distribution. The team continued to release the remaining birds, taking genetic diversity into consideration. By autumn 2023, a total of 59 birds had been released back into the wild, with reintroduction projects also conducted in Fukui and Chiba prefectures.

Today, 558 of the birds soar through Japan’s skies, with some even migrating overseas to places like South Korea and China.

“When we reintroduced the first birds, I worried they might die quickly,” said the park’s former keeper Minoru Funakoshi, 61, who was involved in the 2005 reintroduction.

Back then, Funakoshi was busy traveling nationwide whenever breeding was confirmed to attach leg bands to chicks before they fledged.

“It is wonderful to see the population grow this much,” he said. “I hope they become birds cherished by the Japanese.”

Breeding environment

In recent years, chicks have been born across a wide area from the Hokuriku to the Kyushu regions. Konotori naturally prefer areas rich in food, such as rice paddies.

“They could expand their habitat to the Tohoku region and Hokkaido, where rice farming is thriving,” said Takayuki Funo, 48, the park’s chief researcher.

However, the growing population has given rise to concerns over competition for breeding sites. Many bird species build their nests on utility poles and other structures, posing a risk of electrocution.

“An increase in the population is outpacing the development of suitable breeding environments,” University of Hyogo Associate Prof. Tomohiro Deguchi said. “Local governments are urged to take the lead in ensuring abundant feeding grounds, such as by leaving rice paddies flooded during winter and reducing pesticide usage.”

63 species under conservation programs

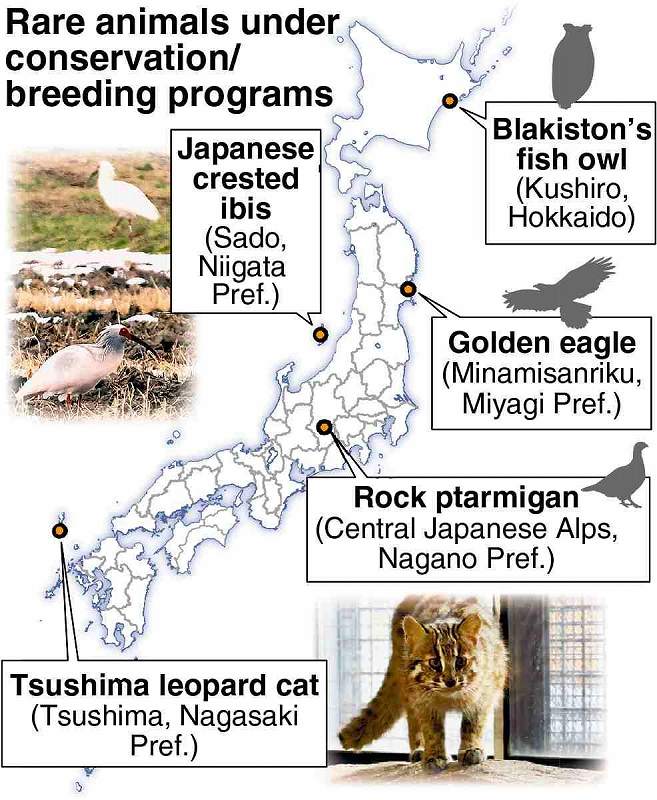

The central and local governments are running conservation and breeding programs under the Law on Conservation of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora to increase the populations of endangered species, with 63 species covered by these programs as of the end of March.

Efforts to reintroduce animals to the wild are progressing, but their numbers remain very small.

GRAPHICS: THE YOMIURI SHIMBUN

A rock ptarmigan, a Special Natural Monument, had once gone extinct in the Central Japanese Alps in Nagano Prefecture due to attacks by raccoon dogs and foxes, which invaded its high-altitude habitat. Since 2020, the central government has released artificially hatched chicks, and now 190 ptarmigans are estimated to live in the Central Japanese Alps.

The population of Tsushima leopard cats, found only in Tsushima, Nagasaki Prefecture, has dwindled to fewer than 100 by one estimate due to factors such as the animal being hit by cars and a lack of mice for prey caused by increasing deer populations.

Efforts to return rescued leopards to the wild are underway, but a significant recovery in numbers cannot been achieved without improvements to the habitat.

Takuma Kaito, a senior ranger from the Kyushu Regional Environmental Office, said, “Our goal is for the animals to survive stably in their natural state, but we are still far from achieving that.”