July 27, 2023

KATHMANDU – The internet is a big scary place. Every time I go on Instagram and Twitter, I promptly log off with a sense of dread. Hate and spite are rampant in ‘intellectual’ circles and among those not so nuanced with their contempt. I especially feel for famous women—in recent context, a certain Miss Nepal and an actress whose partner passed away unexpectedly—who are under so much scrutiny that I worry for them, but I also selfishly relish that I’m not them.

If you look at the comments on their social media handle—people are blatantly nitpicking every aspect of their lives—asking them to explain all of their actions, as if the public is owed a window to every second of these women’s lives. The advent of the ‘world wide web’ certainly carried bigger dreams, but now, I feel like it’s become a place to bicker, hate and hate some more.

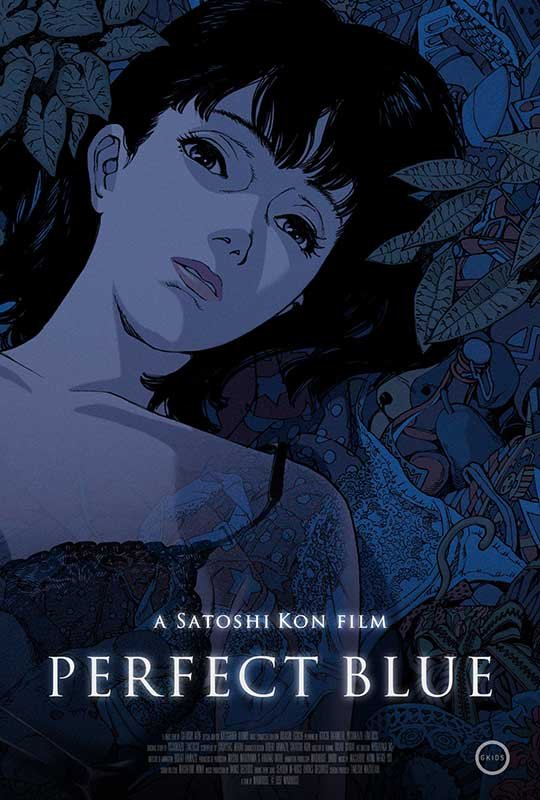

One filmmaker from Japan predicted this unprecedented phenomenon. In 1997—when the internet was gaining momentum—Satoshi Kon directed an animated film called ‘Perfect Blue,’ a movie about the Japanese pop idol Mima and the surreal and cataclysmic effects of her transition from a J-idol to a mature film actress. The film is based on the novel ‘Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis’ by Yoshikazu Takeuchi.

You May Like

‘Perfect Blue’ is an iconic film in many ways. It is an example of early instances of animation moving away from its bubbly, cartoonish image—proving that the medium can be used to tell complex and thrilling stories.

Mima is part of a popular girl group called CHAM!. These girls are ‘marketed’ as ultra-feminine, almost child-like, innocent angels whose personas lie on the cusp of innocence and sexiness. They are commodities solely for the male gaze.

This is evident through the fans—or otakus (a term for young people who are obsessed with particular aspects of pop culture), who are primarily made up of adult men. Many of these men believe that spending large chunks of money on CHAM!’s concerts, albums, and fan meets gives them the liberty to control these girls’ lives. (Is anyone reminded of K-pop?)

So, many aren’t pleased when Mima makes the shift to an actress, and that too begining with a TV programme where her character gets raped. Her manager and confidant, Rumi (a former idol herself), is also displeased when she agrees to do the shoot.

One such extreme otaku is Me-Mania, an adult male whose entire room is filled with Mima’s photographs. He also actively follows an online website called ‘Mima’s Room’, which details her everyday life.

It is Mima’s discovery of the website that leads her down a path of total psychosis. The website details every second of her life, from what she did that day—in her private sphere—to what she thinks. This, along with the added pressure of her new career, derails her mental condition to a point where she stops differentiating between reality and imagination.

Through the website, it is revealed that someone is monitoring every second of her life so closely that they can predict and, thus, manipulate her thoughts. Eventually, those associated with her rape scene (the writer, director and production crew) also die mysteriously, pushing Mima into a deeper spiral.

It is impressive and, at the same time, incredibly nihilistic to see how well this movie has aged—mainly in terms of how it views the corrosion of the sense of self in the digital world. The toxic celebrity culture—think Britney Spears’ 2007 media smear campaigns—is foreshadowed in the film. It shows how the internet—which has blurred the lines between the private and the public—has led many of us to believe that we are acquainted with a certain somebody via their digital presence so well that we have a say in their lives.

Some take this delusion too far and are willing to dictate the direction their favourite celebrities’ lives take. In the K-pop world, they are called ‘sasaengs’—obsessive fans who perch around K-pop celebrities’ houses, call them incessantly and follow them everywhere they go. In 2011, Taeyeon, a member of the girl group Girls Generation, was pulled off the stage by a man who managed to evade security and jump on stage while the group was dancing.

And perhaps the internet isn’t solely to blame. In both the fictional CHAM! and (the very real) Girls Generation, it is their company that markets these women as surrogate girlfriends for their ‘fans’—the vlogs, the interviews, and fan-meets help fuel that fantasy. What these disillusioned fans fail to realise is that all of these are simply marketing tactics, pushing them to spend as much money as possible—which, by the way, rarely makes it to the women.

‘Perfect Blue’ alludes to how digital spheres help create a false sense of closeness among viewers and celebrities, which fuels the dangerous delusions of individuals willing to overlook the apparent marketing tactics.

Meg Sipos from ‘The Other Folk’ mentions in her succinct analysis of ‘Perfect Blue’ that the ‘world wide web’ has become a haven for “voyeurism, objectification, stalking, identity theft, intimidation, dehumanisation, and in some cases, violence and murder—because no species commit terrible atrocities upon itself like humanity.”

This review felt pertinent at this time mainly because of what I see online. We’re living in strange times—our physical and virtual identities are blurring to a point of no return. And as I scroll more and more, it feels like I’m staring into a bleak future, one that Kon warned us about.

Perfect Blue

Language: Japanese

Cast: Junko Iwao, Rica Matsumoto, Shiho Niiyama,

Year: 1997

Duration: 1 hour 21 minutes

Available on: Prime Video