June 9, 2023

MANILA, Philippines — A pair of Philippine Eagles need 4,000 to 11,000 hectares of forest land to thrive in the wild, but based on government data, the Philippines already lost millions of hectares of forests, making it tougher to conserve what is left of them.

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources’ (DENR) Biodiversity Management Bureau described the Philippine Eagle as a “national treasure,” which can be considered as the “Filipino nation’s gift to humankind.”

But while the giant bird of prey “continues to soar amidst the threats it is facing that are caused by humans,” the DENR said “we [should] stand as strong individuals determined to work together […] to protect and conserve [them].”

The Philippine Eagle Foundation (PEF) said the bird species, which is one of the rarest in the world, is now listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, with an estimated number of only 400 pairs left in the wild.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

This was the reason that the celebration of the 25th Philippine Eagle Week this year highlighted the need to “conserve and protect their forest habitats” since “there is no limit to what we can accomplish when we strive and work together.”

As the DENR stressed, “when we conserve and protect their forest habitats, we conserve future generations of Philippine Eagles.” This, it said, will allow new generations to thrive and co-exist with other threatened wildlife.

PH symbol of strength, greatness

It was in 1995 when then President Fidel Ramos signed Proclamation No. 615, declaring the Philippine Eagle, which can only be seen in four islands in the Philippines—Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao—as a national bird.

Scientifically known as Pithecophaga jafferyi, Ramos said the Philippine Eagle is a source of pride: “[Its] uniqueness, strength, power, and love for freedom exemplifies the Filipino people.”

“The Philippine Eagle offers immense ecological, aesthetic, educational, historical, recreational and scientific value to the Philippines and the Filipino people,” Ramos stressed.

Then in 1999, “to instill into the minds of the Filipino people the importance of the Philippine Eagle,” then President Joseph Estrada signed Proclamation No. 79, declaring June 4 to 10 of every year as Philippine Eagle Week.

He had stressed that despite the recognition of its dire conservation status, the Philippine Eagle continues to be caught for illicit trade, so a concerted effort from all sectors of society is needed to ensure their protection and perpetuation.

Through Proclamation No. 79, all government offices, agencies and instrumentalities are urged to implement activities focusing on the Philippine Eagle and its habitat. All non-government organizations are also encouraged to take part.

Struggles

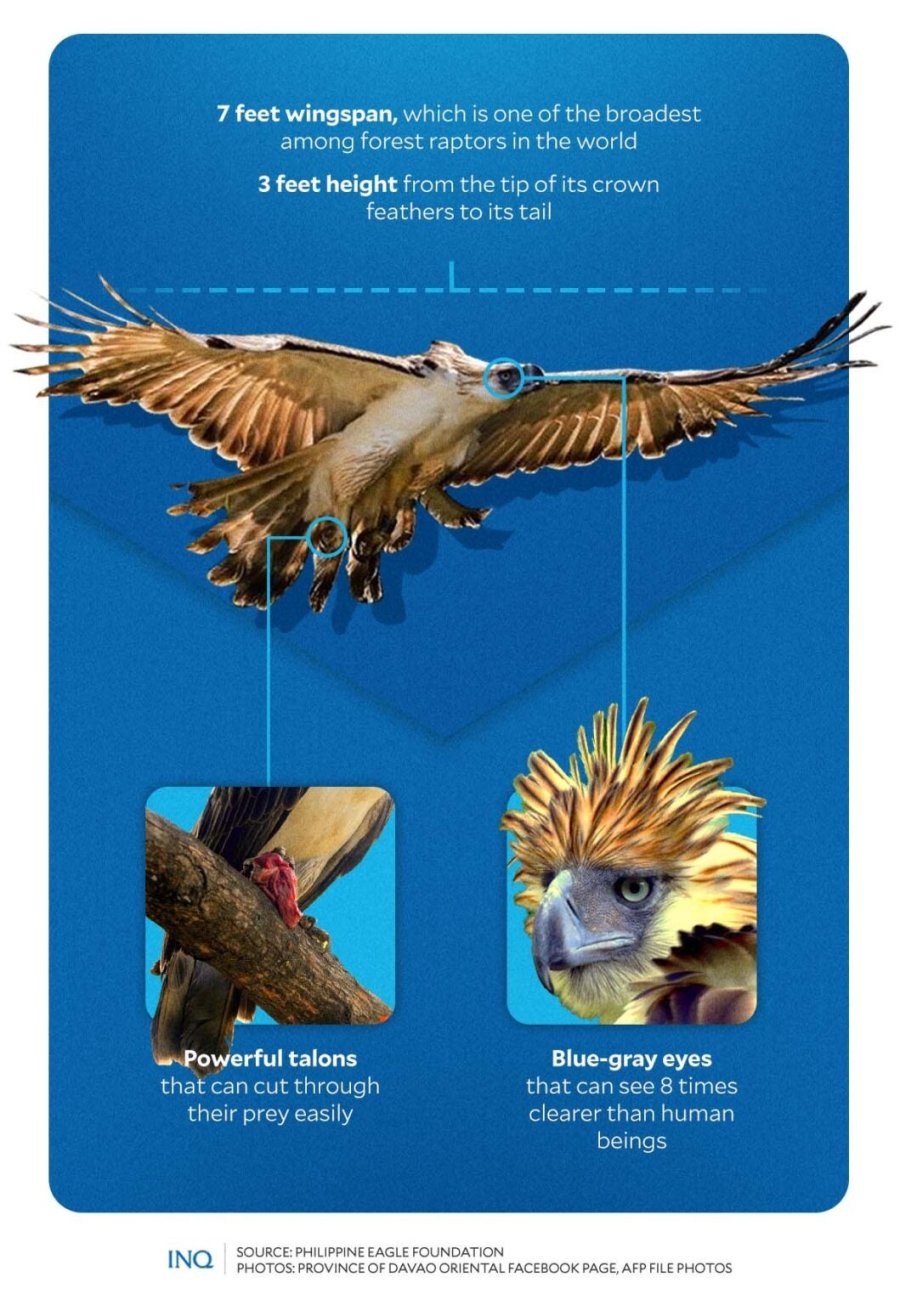

With a height of three feet from the tip of its crown feathers to its tail, the Philippine Eagle is considered the largest forest raptor in the Philippines. It also has a seven-feet wingspan, one of the broadest in the world.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The Philippine Eagle has blue-gray eyes, too, and as the PEF stated, they can see eight times clearer than human beings. Its powerful talons, or claws, meanwhile, can cut through prey so easily.

But through the years, as stressed by the DENR, the bird species was not spared from threats, with loss of habitat and indiscriminate shooting as some of the main causes of their decline.

The PEF said at least one Philippine Eagle is killed every year because of shooting: “As more of our forest is lost, Philippine eagles go farther and farther from their usual hunting grounds in search for prey to hunt.”

“This usually brings them towards human settlements and their livestock, which often results in conflict, with the Philippine Eagle on the losing end,” the PEF stated on its website.

Likewise, illegal logging and irresponsible use of resources have resulted in the disappearance of their forest habitat that brings deadly consequences to the bird species.

“The forest is the only home for the great Philippine Eagle. It is where they obtain food, reproduce, and nourish their offspring,” the PEF said, stressing that the bird species is “solitary and territorial creatures.”

Based on 2020 data from the DENR, only seven million hectares of forest cover are left from the 27.5 million hectares in the 1500s, when the population was still far from reaching over 100 million.

The PEF said a Philippine Eagle typically nests on large dipterocarp trees like the native species Lauan. The Red Lauan, however, the DENR said, is now considered a “vulnerable” species.

Saving them from extinction

Based on data from the PEF, Philippine Eagles take five to seven years to sexually mature and that they only lay eggs every two years. “They wait for their offspring to make it on their own before producing another offspring,” PEF said.

“The egg is incubated alternately by both eagle parents for about 58 to 60 days, with the male eagle doing most of the hunting during the first 40 days of the eaglet’s life while the female stays with the young.”

As stressed by PEF, “the fate of our eagles, the forests and our children’s future are inextricably linked” since “saving the Philippine Eagle means protecting the next generation of Filipinos.”

“As the species on top of the food chain, the Philippine Eagle has a crucial role to play in keeping the gentle balance of the ecosystem in check. It helps naturally regulate species population and provide an umbrella of protection to all other life forms in its territory.”

“An abundant Philippine Eagle population signifies a healthy forest,” it said.

Likewise, “ensuring the safety of Philippine Eagle population in the upland areas can result in additional sources of income for the marginalized communities sharing the forest with the eagles through our biodiversity-friendly initiatives.”

The DENR, meanwhile, said “as the Philippine Eagle struggles, so do we, but this will get easy when we unite and set aside our differences.”

It stressed that “our alliances have forged stronger ties among partners in protecting the species and when we divide these tasks, we multiply our victories. The continuing conservation efforts to ensure their viability and to further propagate the species is our utmost concern.”

“By conserving our national patrimony and strengthening our advocacies, we are able to improve and harmonize conservation efforts to put forward strategies and to curb the direct and indirect threats to Philippine Eagle populations with relevant conservation actions concerning law enforcement, management of captive and wild populations, research and conservation education,” the DENR said.

It stressed that “we press on to achieve more successes in attaining our objectives, which is to save the Philippine Eagle from the brink of extinction.”