April 28, 2022

MANILA — As soon as Vice President Leni Robredo hit the hustings in her hometown of Naga City in Camarines Sur, bite-sized videos bearing false claims related to the presidential hopeful started circulating on social media.

A short video taken during her proclamation rally on Feb. 8, viewed hundreds of thousands of times on Facebook and on TikTok, a popular entertainment platform among the youth, contained altered audio that made it sound like her audience was chanting “BBM” in support of her main rival Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.

In another misleading TikTok video, Robredo was accused of cheating during the CNN Philippines presidential debate because she appeared to be checking notes while answering a question about the West Philippine Sea. In fact, they were notes she had taken during the debate, not “kodigo” (cheat sheets).

These are the kinds of video content that Hannah Barrantes, a corporate lawyer who does independent fact-checking on TikTok, fears: short, entertaining, and digestible propaganda based on falsehoods that are swiftly shared “without leaving anything to ponder on.”

With only a handful of legitimate fact-checkers in the media industry, disinformation on the platform has become so widespread that independent fact-checkers like Barrantes and others — or “TruthTokers” as they call themselves — felt compelled to clean up the platform.

“While we aren’t yet the majority on the platform, it’s satisfying to see real people pushing back (against disinformation) there,” she said. “It also leads to a ripple effect, where former staunch supporters whom we engage (became) enlightened and shift their options.”

Constant battle

TruthTokers are in a constant battle against misinformation and disinformation. Misinformation spreads wrong or misleading information as facts, regardless of whether there is intent to deceive. Disinformation is more insidious as it is the deliberate dissemination of false or fabricated information to mislead or deceive the public or a certain group.

Academics are seeing the potential of “emerging platforms” like TikTok, one of the top apps downloaded in the country last year, for sowing disinformation.

A study published by Internews in December 2021 on emerging social media platforms observed “misinformation and disinformation on TikTok videos, particularly on COVID-19 and the upcoming 2022 Philippine general elections, with fairly huge engagements, although it is difficult to discern how extensive the reach of such content is.”

Engagement

Internews is an international nonprofit organization that supports civil society groups and local media in promoting trustworthy, high-quality news and information.

On larger platforms like Facebook and YouTube, influencers and online celebrities often dictate the narrative, including false claims and propaganda.

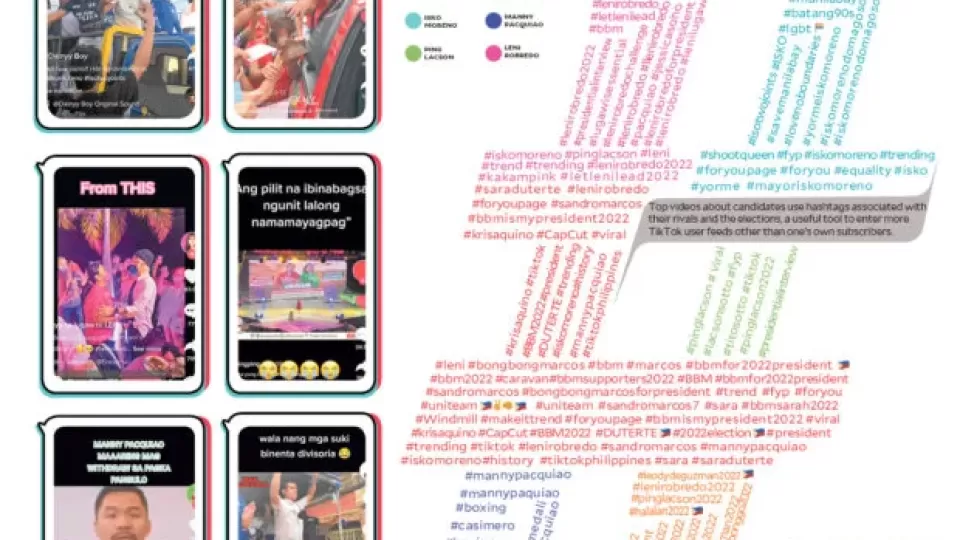

But in TikTok, users and influencers or content creators use what is viral, whether it’s a trending sound, filter, dance choreography or hashtag, according to Samuel Cabbuag, assistant professor in sociology at the University of the Philippines and one of the authors of the Internews study.

“This is how they manage to be more visible in the app, and thus get more views, engagement and followers,” Cabbuag said.

Engagement is a measure of the number of views, shares, and comments that a TikTok post has generated.

The Internews study noted that false or misleading content on this platform were “created, or engaged with by both anonymous and identified accounts,” indicating that the form of disinformation here “is more organic and authentic relative to other platforms.”

Barrantes said she makes TikTok videos to explain how laws are interpreted.

Some of the content she had seen in similar videos were “just pure propaganda, with ‘pseudo-intellectuals’ using legal terms interpreted in a wrong way.”

She encountered TikTokers who claimed that the only law which branded the Marcoses’ enormous wealth as ill-gotten was the late President Corazon Aquino’s Executive Order No. 1, which created the Presidential Commission on Good Government to recover an estimated $10 billion of the family’s ill-gotten wealth.

‘How sick was that?’

“They argued that if EO1 was not drafted by [Aquino], then the Marcoses’ wealth is not ill-gotten. How sick was that?” Barrantes said. “We have Supreme Court cases that recognized the Marcoses’ ill-gotten wealth.”

But aside from attempting to question established facts and whitewash history, the videos that Barrantes encountered were also direct attacks against Robredo, who beat the ousted dictator’s son in the 2016 vice presidential polls.

This is consistent with the preliminary findings of Tsek.ph, an academe-based fact-checking group. It said that Robredo had been the “biggest victim” of disinformation, while Marcos was its main beneficiary.

As one of the self-organized TruthTokers, Barrantes engages troll armies head-on with counter-disinformation videos. She eventually volunteered to disprove false law-related claims against Robredo.

There are now many video creators trying to push back against disinformation, she said.

“But we’re still powerless against groups who have the machinery to churn out more and more untruths,” said Barrantes.

Open letters

She considers the TikTok algorithm a blackhole, where watching one false video would lead a person to more similar content until the platform traps users in an echo chamber.

“We are also aware — and afraid — that in fighting disinformation on TikTok, there’s a tendency for us to be trapped in our own echo chambers. The task is to bring more people to the ‘truth algorithm,’” she said.

In December last year, the Movement Against Disinformation (MAD), a nonpartisan network of individuals and groups, wrote open letters to TikTok, Google and YouTube urging them to be transparent, accountable and proactive in countering false information.

MAD specifically asked TikTok to replicate measures it put in place for the 2020 elections in the United States when it removed false or manipulated videos or had tagged them as “not eligible for recommendation.”

In response, TikTok Philippines public policy head Kristoffer Rada vowed that it was committed to fight online disinformation. It said it was already implementing several of MAD’s suggestions, and promised to “continue to do so until the end of the 2022 elections.”

But MAD convener Tony La Viña said that while the platform’s policies were good, the problem with TikTok was in its “consistency” in implementing those policies and in the lack of “promptness” in responding to complaints and in immediately taking down false claims.

“And each day that a piece of fake news stays on TikTok, [you] can imagine how it’s played again and again,” he said.

There is a need for the platform to do more content moderation and to act more decisively in rooting out disinformation, he said.

Accountability

Celine Samson, head of the online verification team of Vera Files in its partnership with Tsek.ph, said that it was important for social media giants to be accountable for disinformation “because it is through these platforms that these narratives are circulated.”

“We’ve seen many of these platforms — Meta, YouTube, Google — have stringent policies relating to COVID-19 and vaccination, but unfortunately the same cannot be said on historical revisionism and disinformation,” Samson said.

According to La Viña, it is important to consider that although TikTok does not have as many users as Facebook, they are mostly young people — a huge component of registered voters in the elections.

Aside from this demographic, La Viña said the nature of the medium-short, shareable videos can do immense harm on the youth.

“The medium is the message, and the medium dictates also the message,” he said. “To some extent, it limits the kind of content you can put on TikTok, but it can be much more effective, and you can reach more people.”

In an email to the Inquirer on Wednesday, TikTok Philippines lead for communications Conrad Bateman said TikTok was “committed to providing access to trustworthy and relevant information for our Philippine community, particularly over the course of the 2022 elections.”

With the support of the Commission on Elections, Bateman said that TikTok Philippines launched an in-app election guide that encouraged its users to vote and provided “authoritative information” on the election process.