January 10, 2022

While the common narrative surrounds RCEP’s benefits, there are drawbacks. But Cambodia is willing to look past them for the greater good

Two trade pacts coming into force in Cambodia this year have raised the “feel good” factor for economic recovery, as effects from the latest Covid-19 variant threaten to impact growth.

The deals – 15-party plurilateral Regional Comprehensive Economic Agreement (RCEP) and the China-Cambodia Free Trade Agreement (CCFTA) – have been long anticipated by business sectors due to its promise to boost exports and investments.

However, several issues, often less discussed, play out in the background, such as the threat of a widening trade deficit, the possible loss of competitiveness, reduced tax revenue, and the risk of protectionism – the latter arising from uncertainties posed by the pandemic.

That said, there is a good chance for positive impacts to show immediately from the deals, particularly RCEP, even though the agreement has a 20-year implementation period, which includes the lowering of tariffs to zero.

Dr Jayant Menon, visiting senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, who made this assertion on Al Jazeera’s Inside Story on December 31, however, said, “given that RCEP is a long-term project, significant reforms in the agreement that deal with difficult and challenging issues would be backloaded, [meaning that] it would be left towards the end as these things naturally work out”.

Asked to elaborate, Dr Jayant told The Post that the immediate impacts from RCEP’s entry into force will come from tariff reductions amongst member countries, relating to the chapters on Trade in Goods, Rules of Origin and Customs Procedures and Trade Facilitation.

“These are often described as ‘low hanging fruit’ reforms. The more difficult areas relate to chapters dealing with Trade In Services, Intellectual Property, E-Commerce, Competition, Government Procurement and the like.

“Apart from being more complex to implement, the adjustment costs can be higher in the short term, leading to vested interests pushing for deferral, to a watering down,” he warned.

The RCEP was ratified by 11 out of 15 countries, including five non-ASEAN states, which satisfied the quorum to get the deal off the ground this year.

For South Korea, the agreement will take effect on February 1, 2022, which is 60 days from its date of ratification.

Countries that have yet to ratify the RCEP consist of Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar and Philippines.

Deteriorating trade balance

For Cambodia, studies by the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) revealed that exports could grow up to “18 per cent annually from 9.4 per cent”, said Penn Sovicheat, undersecretary of state for the Ministry of Commerce.

This figure would contribute “3.8 per cent to economic growth annually from two per cent” while job opportunities would increase to “6.2 per cent from 3.2 per cent per annum”.

In ERIA’s 2015 report, which has yet to be made public, Cambodia stood to “gain” the most in “real gross domestic product (GDP)”, as per results of its baseline scenarios.

It inferred that the removal of high import tariffs, which Cambodia currently uses for physical capital, would reduce the price of capital goods, and in turn encourage more investment, leading to improved real GDP gains.

The findings are widely supported by experts who concur that the zero tariffs would spur more investments, improve productivity and improve economic growth.

But this policy would also lead to a surge in imports, leading to a trade imbalance, according to a study by analysts Dr Rashmi Bangar and Prerna Sharma, who are with UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), and Dr Kevin P.Gallagher, a professor of global development policy at Boston University.

The 32-page working paper titled RCEP: Goods Market Access Implications for ASEAN analyses RCEP’s Goods Chapter to ascertain whether market access can be achieved by developing countries through RCEP. It was published by Boston University’s Global Development Center last year.

The study showed that RCEP countries already have existing FTAs or are negotiating among themselves amid the existence of individual FTAs between ASEAN and the five non-ASEAN states.

“Any additional market access for ASEAN can therefore be gained from RCEP only if deeper tariff liberalisation is undertaken, which cuts through the existing sensitive lists of the member countries,” they said.

Pre-RCEP, the study showed that Cambodia protected 51 per cent of imports under the sensitive list (SL) and tariff-rate quota (TRQ) or limited quota, which serve to safeguard its own sectors.

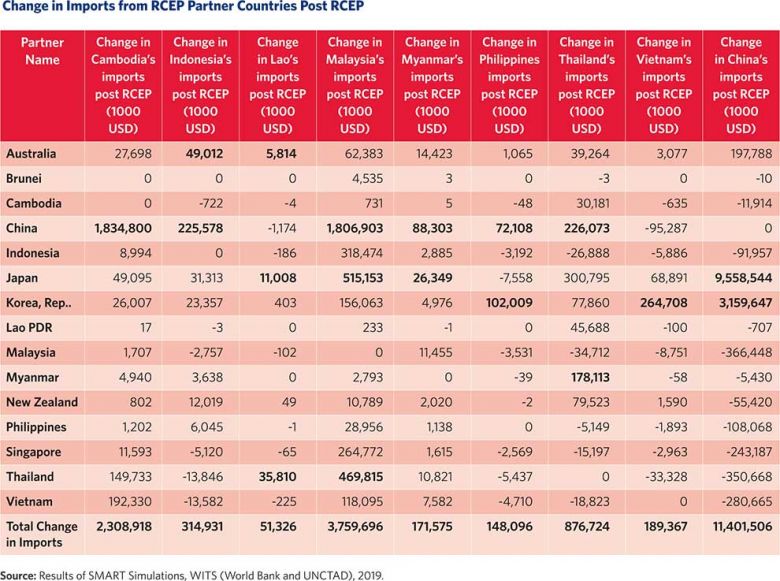

Based on their study using SMART simulations, which are available in the World Bank’s World Integrated Trade Solution, “import increase in absolute terms for Cambodia” is projected at “$2.3 billion per year”, making it the second highest in ASEAN after Malaysia.

The usage of SMART simulations enabled the researchers to estimate of the “impact of tariff reduction at a very disaggregated level” compared to ERIA’s use of computable generation equilibrium model, which “undertakes simulation for broad sectors”.

The Boston University analysis revealed that 79 per cent of Cambodia’s growth imports would be backed by China ($1.8 billion), followed by Vietnam and Thailand.

These imports comprise mainly of textiles and clothing, mechanical appliances and machinery (China), and parts of footwear (Vietnam).

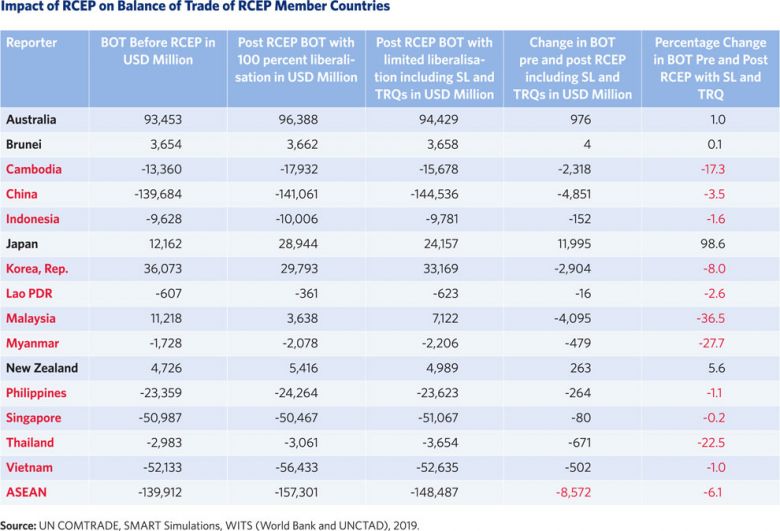

The researchers found that “tariff liberalisation under RCEP will deteriorate the existing balance of trade (BOT)” of ASEAN in relation to RCEP countries by “six per cent per annum”, but BOT “will improve for some of the non-ASEAN countries” in the RCEP.

“The maximum gains in terms of improved BOT will go to Japan, followed by New Zealand. Post RCEP, BOT will worsen for Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam,” they concluded.

Currently, Cambodia is experiencing record trade deficits as a result of increased imports, including gold, that rose 53.5 per cent to $20.6 billion in the first nine months of 2021, the World Bank stated last December.

About one-fifth of the imports at the time – $3.5 billion or an increase of 25.1 per cent year on year – consisted of fabric, indicating a recovery in garment manufacturing as external demand improved.

However, exports eased by 3.5 per cent to $12.7 billion. Together with the “collapse of the tourism receipts” which affected services exports, BOT was impacted.

Source: Working paper ‘RCEP: Goods Market Access Implications for ASEAN’ 2021 (Published by Global Development Policy Center, Boston University)

All of this has put a pressure on the current account that is forecast to widen to 26.9 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2021 from 8.2 per cent in 2020, the World Bank said.

Can trade deficit narrow?

Dismissing a parallel to import and export challenges and a possible trade deficit within RCEP, Ministry of Commerce’s Sovicheat argued that the “deficit is normal”, particularly for least developed countries (LDC) that are starting to build or rebuild its economy.

“We have to appreciate the deficit for some time,” he said, noting that the Council for the Development of Cambodia had approved “many investment projects”, “big and small”, in 2020 and 2021, which resulted in the import of “lots of machinery, material and equipment for construction, et cetera”.

“These contribute to long-term investment and would bring down the deficit. So, part of the deficit is big because of the import of infrastructure equipment, construction materials, materials for garment [and] shoe factories.

“The amount for import is going up most of the time for investment, manufacturing and the development of [the] construction sector, such as housing developments – these contribute a lot to the increase in [import] volume,” he explained.

Sovicheat also revealed that the bigger contributor to import growth is linked to the country’s inability to produce some goods, like oil or gasoline, which is essential for aircrafts and the industrial sector.

“We also import cars [and] machinery for agriculture, so [these] also contribute to the imports [causing] deficit to go up. But for [an] LDC like us, when we don’t have factories … or the competitive advantage … then, we are not able to produce.

“[Therefore] we have no choice but to import, however the deficit is not bad at this time. We do agree that we have to find a way to reduce the deficit,” he said.

What matters however, is that Cambodia stands to benefit from exports due to the demand anticipated via RCEP and CCFTA, as well as the upcoming free trade agreement with South Korea, he noted.

This is complemented by the continued exports of shoes, garments, bicycles and luggages to the West.

“So, we still have hope and [the] ability and potential to increase export … [we] hope [trade] deficit will shrink to [a] level, maybe not surplus, but [to] an acceptable level,” he told The Post.

In the meantime, there will be “lots of things” to import to support future growth, including oil which is something Cambodia cannot produce and would “always contribute” to increased imports.

Which is why trade agreements would help speed up the process of diversification and technical support in the agriculture and industrial sectors, he stressed.

For decades, calls have been made for Cambodia to diversify its economy and export markets from its manufacturing mainstay, garment, travel goods and footwear (GTF), on the basis of eroding preferential treatments as it moves to graduate from LDC status.

Granted, the US and European Union (EU) continue to take up a chunk of Cambodia’s export market, but China has raised its imports of agricultural produce, such as rice and fruits from Cambodia.

As such, Sovicheat believed that investors will take advantage of RCEP and CCFTA to relocate to Cambodia or turn their operations to parts and components manufacturing or diversify the agriculture sector, to engage with newer markets.

Similarly, within RCEP, the policy on rules on origin could see investors collaborating with locals or setting up shop in Cambodia to export to China or leverage on EU and US’ generalised system of preferences for duty-free access into those regions.

“I feel a country like ours has [this] potential because of cheap labour, vast agricultural or fertile land, and the [construction] of new infrastructure, like the deep sea port in Sihanoukville, expressway and proposed railroad and connectivity of Belt and Road,” he said.

Looking at short and medium term expectations, he felt the benefits from the trade deals would show in “three to six years”, including the upskilling of workers and technology transfers.

Internal tax

Against this backdrop though, there is a risk of lower customs tax following the removal of tariff barriers, given that up to 90 per cent of tariffs would eventually disappear to allow for better market access.

For Cambodia, this could translate to “a tariff loss of about $334 million per year or 1.24 per cent of its 2019 GDP”, which is equivalent to its national health expenditure of around 1.3 per cent of GDP, based on World Bank’s World Development Indicator.

While it is not fully clear how many product lines under RCEP will see tariff removal or reduction, an analyst, who declined to be named, said Cambodia has 1,236 products where tariffs have remained for 20 years or in perpetuity.

However, 8,322 products have no transition period or transition periods are shorter than 20 years before the import tariffs are withdrawn, meaning that they are at risk of losing the sensitive list protection.

Separately, the CCFTA covers 10,800 tariff lines for Cambodia and about 9,530 tariff lines for China, the World Bank said.

The CCFTA “goes beyond what was offered under the ASEAN-China FTA, covering an additional 340 tariff lines”, which include live animals and animal products, meat, fish, and cereals.

As of January 1, this year, 98 per cent of the China’s tariff lines will become zero rated, while 95 per cent of the 340 commodities, will not be taxed, the World Bank said.

In the midst, China has been a formidable customer of agricultural produce, particularly milled rice where exports rose 37.7 per cent year-on-year to 200,000 tonnes, half of its total import quota with Cambodia, in the first nine months of 2021.

Source: Cambodia Economic Update, December 2021 (The World Bank)

That being said, the loss of tariffs for Cambodia over time would impact tax revenue if industrial trade and growth remain dim.

On top of that, zero tariffs might lead to price dumping that could affect local industries and producers, dulling market share.

Lim Heng, vice president of Cambodia Chamber of Commerce, is concerned but conceded that Cambodia is “already full of many foreign imports”, given that it is an open economy.

“[Hence, the reason why] we must [stay] competitive. The good thing about small and medium enterprises [SMEs] is that it can increase and update products for competition,” he said.

“As you know, Cambodian economy is still dependent on garment exports, [because of] EBA and GSP from EU and US, and agriculture products too. [With RCEP and CCFTA] and the new investment law, we can benefit … can attract more investments and manufacturers from abroad for the production of [value-added] agricultural goods for export,” he added.

Heng said this direct investment would result in a higher collection of internal tax.

Sovicheat agreed, saying that the government will compensate the “loss” in tax revenue by collecting more internal tax, particularly corporate tax, such as value-added tax, tax on revenue, and profit tax.

“We will compensate with internal tax because people get rich as they are able to export more … and import more. They can make a profit, so the government will [impose tax],” he said, adding that Cambodia also gains from exports to other markets in RCEP.

While not many products are zero-taxed, especially those on the sensitive list, he said the increase in zero tax products in Cambodia is good as it will stimulate competition among local industries.

“The competitive environment has to be maintained. Where there is importation of something with zero tariff and good quality, it will compete with something we couldn’t produce in good quality. It will push the manufacturing industry to try its best, while improving productivity and quality,” he said.

Sovicheat also cited an RCEP clause on cooperation and investment for SMEs where support and technical assistance would be provided to improve quality and productivity and be part of the regional supply chain.

“RCEP has good benefits for us … we can ask for technical assistance. That’s all we expect of RCEP.

“We will get the ‘low hanging fruits’ to export but we are also looking for the fruit on top of the tree in the long run, [which is] investment, technical cooperation, and improvement of the SME sector,” he said.

‘Go out there and do it’

Going forward, Dr Jayant of ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute said some things, like the more challenging bits of RCEP, could take “another decade or so” to work itself out but overall, what is “not observed” is the rise of protectionism.

He said the pandemic has “fuelled an increase in nationalism and protectionism”, and agreements such as RCEP could help to “tie the hands” of members and prevent them from “succumbing to the temptation” to raise barriers.

These barriers could be viewed as protecting jobs and market shares during difficult times, he shared, citing the example of Indonesia’s recent decision to ban the export of coal for domestic reasons.

Given that it has yet to ratify RCEP, it is therefore not bound by its rules, Dr Jayant told The Post. “Hopefully, RCEP will help unwind many of the barriers that have been raised in the name of the pandemic, once the need for them has passed.”

As for the impact on trade in Asia, RCEP will see immediate changes, Beijing-based Einar Tangen, an economic and political affairs commentator, said in response to a question during Al Jazeera’s Inside Story programme last week.

The agreement has given SMEs, in particular, the levy to “simply go out there and do it” because the “same rules now apply to all the markets”, which removes the need to study different markets.

“Plus, these countries especially those at the lower end like Cambodia and Myanmar stand to gain tangible benefits. They have a labour dividend and as you can see with wages rising in the US and other places [with] inflation rearing its ugly head, companies are going to be looking to cut cost.

“There is real possibility that they will start looking at these countries because they are in a recognisable trade zone, that is enforceable and makes things a lot easier that they are within that zone,” he commented in the programme.