January 10, 2023

MANILA — Executive Order (EO) No. 171, which was signed in May 2022 to bring down prices and stabilize the supply of agricultural products, is making life tougher, especially for local meat producers.

The EO modified tariff rates for pork, corn, rice, and coal, heeding the recommendation of the Economic Development Cluster to address the economic impact of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine.

It was signed by Rodrigo Duterte, who stressed that there was a need to reduce the tariff rates for the purpose of augmenting the supply of agricultural products, diversifying the country’s market sources, and maintaining affordable prices.

As a result, the tariff rate for pork was brought down to 15 percent (in-quota shipments) and 25 percent (out-quota shipments), while rice’s was reduced to 35 percent. The tariff rate for corn was brought down to 5 percent (in-quota shipments) and 15 percent (out-quota shipments).

But despite the EO’s intention, which was to facilitate the entry of more agricultural products at lower prices, it was met with strong opposition, especially from local meat producers, who are still reeling from the impact of the COVID-19 crisis.

Looking back, eight agricultural and related groups had stressed that “to give way to meat importation means aggravating the already devastating impact that the stringent lockdowns have brought upon the local ecosystem.”

“Allowing the importation of meat and limiting local production in this critical juncture will cause a stoppage in the operations of some farms,” they warned, saying that “their production cannot be revived for another 12 to 18 months.”

“One can just imagine the despicable damage this could bring to millions of Filipinos reliant on the sector. We trust that this is not what the government wants,” the organizations, including the Philippine Chamber of Agriculture and Food Inc., said.

The Department of Agriculture (DA) which was still headed then by William Dar, responded, stating that the government is only allowing the importation of “deboned” poultry products that cannot be produced by Filipino farmers.

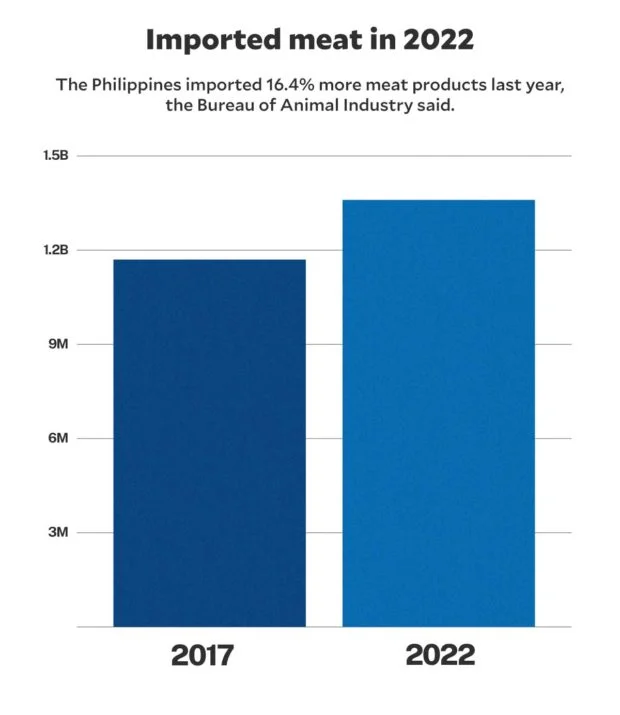

But based on data from the Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI), the Philippines imported 16.4 percent more meat products last year, breaching what the United States Department of Agriculture estimated for 2022—550 million kilos.

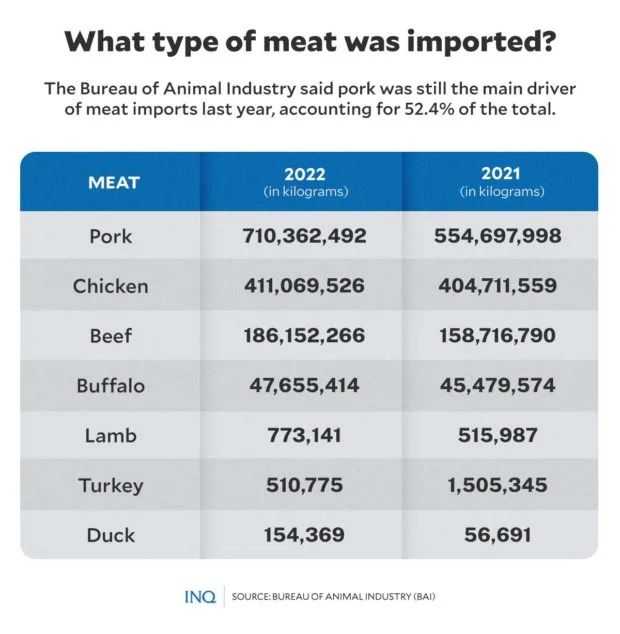

The BAI said meat imports last year reached 1.36 billion kilos, higher than the previous year’s 1.17 billion kilos, with pork making up most of the meat imports—710.36 million kilos or 52.36 percent of all the meat products that entered the Philippines in 2022.

Chicken clinched the second spot with 411.07 million kilos, 1.6 percent higher than the previous year, with deboned chicken and chicken leg quarters as one the most purchased chicken products.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The Philippines also brought in 186.15 million kilos of beef, with beef cuts accounting for more than half of the volume. Some 47.66 million kilos of buffalo, 773,141 kilos of lamb, 510,775 kilos of turkey, and 154,369 kilos of duck were also imported.

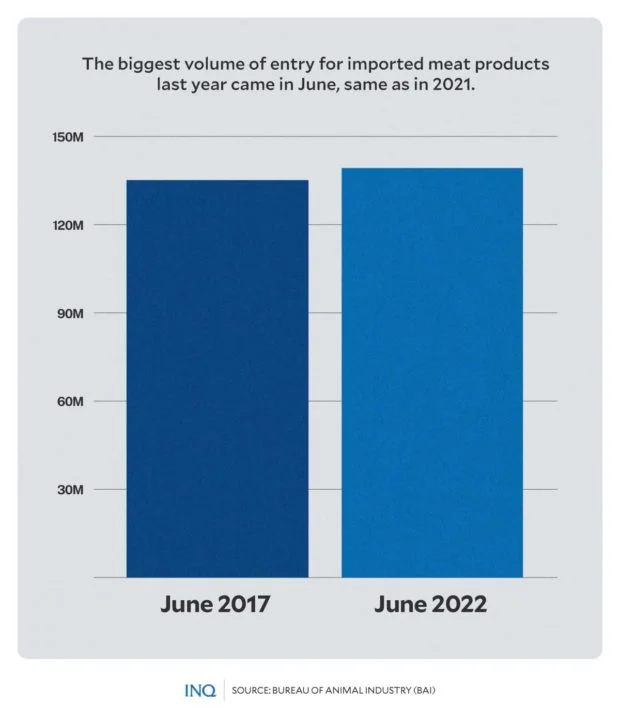

Based on BAI data, June 2022 had the biggest volume of entry for imported meat last year at 139.23 million kgs., same as in 2021 when the largest import was logged in June that year at 135.14 million kgs.

Brazil was the Philippines’ primary source of meat imports with Spain and the United States coming in second and third.

No end in sight

Last Dec. 15, the Pork Producers Federation of the Philippines Inc. called on President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to junk EO No. 171, saying that the continuous decline in tariff rates, especially for pork, should already end.

“Make this your Christmas gift to us, local meat producers,” it said.

It was likewise stressed by peasant group Amihan that the extension of tariff cuts on pork, rice, corn and coal would only mean “destruction of local production and bankruptcy of local food producers.”

Cathy Estavillo, secretary general of Amihan, said importation will not lead to lower food prices: “It seems that this is made to satisfy the greed of the few. It is clearly not in the interest of farmers or of consumers.”

But Marcos Jr., last Dec. 18, approved the extension of the validity of EO No. 171, with the Office of the Press Secretary and the National Economic Development Authority (Neda) saying that this was to “address supply issues and temper inflation.”

Looking back, it was Neda that endorsed the extension until Dec. 31, 2023 for pork, corn, and rice, and beyond 2023 for coal, stressing that this will help poor Filipinos struggling to make ends meet because of high inflation.

Rosendo So, president of the Samahang Industriya ng Agrikultura, had said in a radio interview that despite the oversupply of imported frozen products because of the reduced tariff rates, retail prices of pork remain high.

“The live weight of pork is only pegged between P170 and P180, but the retail price of pork kasim is at P300 per kilo Imported frozen pork products should be sold at P220 per kilo as importers bought them at P120 per kilo,” So said.

“The traders are taking advantage while the DA fails to address the issue. The low tariff on imported meat products did not help in bringing down the retail price of pork,” So had stressed, saying that retail prices of pork kasim and pork liempo should only be at P270 and P300.

Boost local production instead

Estavillo said they are opposed to the extension of EO No. 171, saying that the government should instead boost local production or issue an executive order that will directly bring down prices of agricultural products.

“Production subsidy and assistance are what farmers need the most. Filipino rice farmers lost an estimated P206 billion for the first three years of RLL which triggered depressed palay farm gate prices while rice prices remain unaffordable for the poor and marginalized consumers,” she said.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The government should instead provide necessary and appropriate production support to local farmers to boost production and improve farmers’ welfare,” Estavillo stressed.

She said “Marcos’ neoliberal policies on agriculture including import dependence and agricultural neglect are contributing factors in the current food crisis. Reliance on a very limited and volatile global market for the country’s food security does not in any way guarantee food availability, accessibility and stability.”

She explained that for the country to attain food security and self- sufficiency, policies and programs should address the issues faced by the most important component of food production – the producers. Policies that maintain monopoly of land and other resources keep food producers and most of the population poor and food insecure.

“We reiterate our demand for immediate distribution of P10,000 cash aid and P15, 000 production subsidy for the farmers, peasant women, agricultural workers, fisher folk and other rural-based sectors,” she said.