October 17, 2022

JAKARTA – Social media will play a central role in the 2024 general election, as politicians double down on their online presence to woo young voters who use such platforms as their main source of information.

But memories of widespread online misinformation and bitter polarization in previous elections still linger, prompting questions of whether election organizers will manage to protect digital discourse from such pitfalls this time around.

A recent survey by the Jakarta-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) focusing on the electoral outlook of prospective voters between the ages of 17 and 39 showed that social media was the go-to source of information and platform for political expression for young people.

Fifty-nine percent of respondents said they got their information on current events chiefly from social media, while 32 percent said they got it from television. The proportion of people who preferred social media nearly doubled from a similar 2018 survey. Television was the preferred choice in 2018, with 41.3 percent of respondents citing it as their chief source of information.

The survey also showed a significant increase in the number of social media accounts that people used across different platforms.

“I think social media [campaign success] will be the most sought after in the upcoming elections. Aside from its prominence, social media campaigns are cheaper, farther-reaching and can be done more frequently than public gatherings,” said Arya Fernandes, head of the CSIS department of politics.

Social media darlings

A growing number of presidential hopefuls have embraced and sought to bolster their popularity on social media – a decision that experts say will be key in the upcoming race.

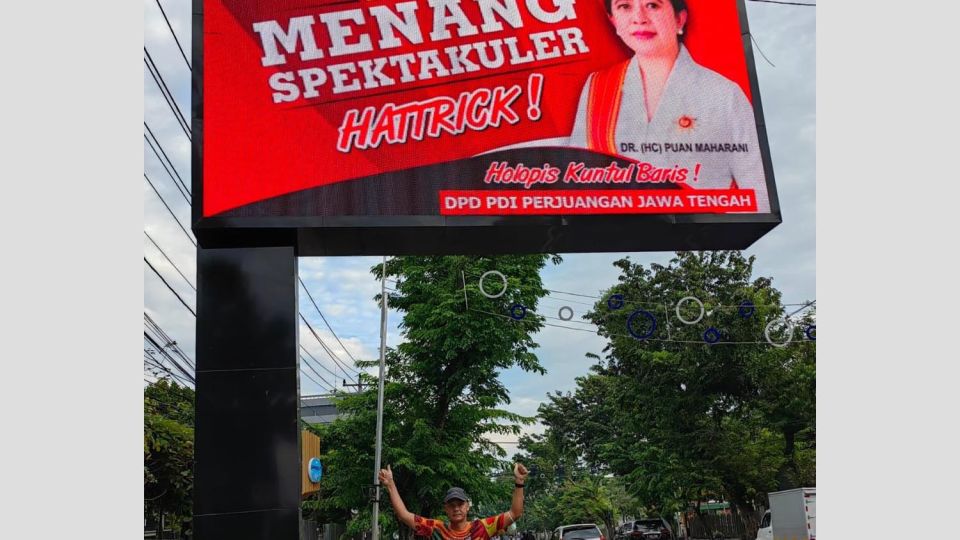

Central Java Governor Ganjar Pranowo of the ruling Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), for instance, has long benefited from the popularity of his online persona, edging out internal party favorite Puan Maharani, the daughter of chairwoman Megawati Soekarnoputri, in public opinion polls.

He recently caught the attention of Indonesian netizens after posting a picture of himself on Twitter in which he was posing underneath a huge banner of Puan without his trademark smile. His caption reads, “Ready!” – but for what and against whom were left indeterminate, eliciting speculation from commenters.

[https://twitter.com/ganjarpranowo/status/1576532282445160448/photo/1]

Ganjar, who has consistently ranked among the top three potential contenders for the presidency in recent months, looks likely to be snubbed by party elites, who are pushing to award the party’s nomination to House of Representatives Speaker Puan, despite her notably low electability polling. She had been favoring a more traditional approach, paying in-person visits to political bigwigs to promote herself and gauge her chances.

The “Ready!” picture had garnered 10,700 Twitter likes and 1,180 retweets as of Thursday, and a post with the same photo and caption had been liked 190,731 times on Instagram.

Another top presidential contender, outgoing Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan took to Instagram to tell his 4.6 million followers that the NasDem Party has backed his candidacy. The post had been liked over 289,000 times as of Wednesday.

[https://www.instagram.com/p/CjPMFQEP7uM/]

“[A large following] on social media is certainly something to be reckoned with in the 2024 election,” said political analyst Firman Noor of the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN). “Presidential campaigns boil down to getting a candidate’s message across to as large an audience as possible, something social media is very effective at.”

While some presidential hopefuls have managed to find success on social media, others seem to have fallen short.

Coordinating Economic Minister and Golkar Party patron Airlangga Hartarto, for instance, recently faced criticism over what social media users considered an “insensitive” post on the recent soccer stampede in East Java that killed scores of people. The post had offered Airlangga’s condolences but stuck with his campaign power pose, complete with yellow attire and a clenched fist.

[https://twitter.com/hansdavidian/status/1576493293734572032/photo/1]

Meanwhile, the PDI-P’s Puan unintentionally went viral in a video clip showing her giving away social aid packages to a crowd on a recent visit to West Java – with what many social media users took to be a sullen expression on her face. One user edited the clip to make it appear as if he was parrying away the packages being thrown by Puan. The meme was reposted numerous times.

[https://bangka.tribunnews.com/2022/09/28/heboh-puan-maharani-cemberut-saat-bagikan-kaos-ke-warga-ternyata-ini-penyebabnya]

Better regulations

Experts are calling for more consistent law enforcement and grassroots-level efforts to mitigate the risks of social media campaigning, including the misinformation and hate speech that colored the past two presidential elections.

The 2014 and 2019 presidential races, which both pitted current President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo against his political rival and later ally Prabowo Subianto, were marred by political polarization.

Despite a number of General Elections Commission (KPU) regulations intended to prevent hate speech and discrimination in the campaigns, the opposing camps tore each other up on social media.

At the time, social media-specific provisions only focused on the number of social media accounts a political party or presidential candidate was permitted to manage.

“These regulations are not enough […]. The problem now is that these negative messages will not come from [a party’s or candidate’s] official accounts but from bot accounts or ‘buzzers’. The question is, how will the KPU counter this?” said Khoirunnisa Agustyati of the Association for Elections and Democracy (Perludem).

As opposed to policing every single social media account, Khoirunnisa said the KPU was better served by educating the public about the threat of misinformation and hate speech using public forums, including social media platforms themselves, and by fact-checking claims made online.

“In the 2019 elections, some fake news circulated focusing on the KPU, accusing it of sending out pre-signed ballot papers to voting booths. If there is no strategy [to counter this], the public might lose faith in the integrity of the electoral process itself,” she said.

Separately, Idham Holik of the KPU told The Jakarta Post that the commission would continue to focus on passing more pertinent regulations, particularly on electoral districts and updated voter data.

He also said the KPU would facilitate public discussions to devise more social-media-specific regulations by the start of next year.