July 3, 2023

SEOUL – Support for same-sex marriage is gaining ground in South Korea, but the pace has been slow compared to neighboring countries, with increasingly polarized views on the issue.

Korea has yet to legalize same-sex marriage, unlike 34 other countries where marriage equality either became law or was recognized in court rulings, according to the Human Rights Campaign Foundation.

Taiwan has not only legalized same-sex marriage, but also granted adoption rights to same-sex couples.

Meanwhile, Japan’s ban on same-sex marriage is “in a state of unconstitutionality,” according to court rulings, including the latest in a Fukuoka district court in June, though some other courts in Japan reached differing conclusions.

In Korea, neither a Supreme Court ruling nor a Constitutional Court ruling — binding in all courts across the nation — has recognized the legitimacy of gay marriage.

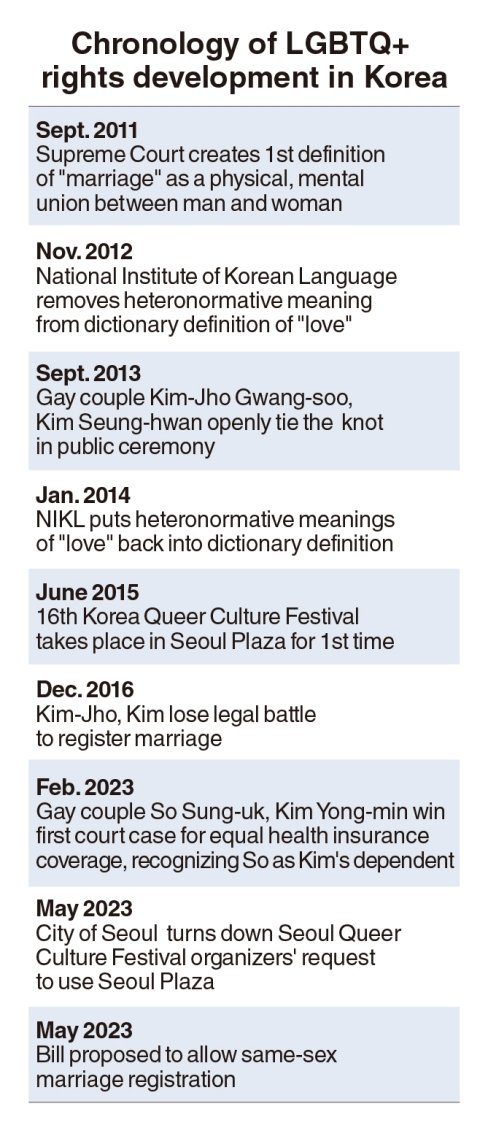

No specific clause in either Korea’s Civil Act or the Constitution clarifies whether two people of the same gender can legally marry or not. Only a 2011 Supreme Court ruling, the first of its kind, defined marriage as “a physical and spiritual relationship between a man and a woman.”

Film director Kim-Jho Gwang-soo and film distributor Kim Seung-hwan — a gay couple who publicly tied the knot in 2013 — acted in defiance. They took a district office to court, demanding it accept their registration as a family, only to lose the case in December 2016 at an appellate court. They did not appeal to the Supreme Court.

But a more recent ruling in February this year by couple So Sung-uk and Kim Yong-min recognized a nonearning partner as a dependent of the earning partner under Korea’s national health insurance system. However, it stopped short of recognizing them as a married couple, not reversing the 2011 Supreme Court decision.

Even official definitions of the word “love” have been a battleground. Since 2014 Korean dictionaries have described romantic love as being between a man and a woman. The National Institute of Korean Language removed heteronormative definitions for five words, including “love,” in 2012, but backtracked in 2014 following opposition from conservative groups.

Rep. Jang Hye-young, a lawmaker of minor progressive Justice Party, speaks during an interview with The Korea Herald at the National Assembly. (Im Se-jun/The Korea Herald)

Advocates point out that Korea has yet to come up with statistics specifically pertaining to LGBTQ+ communities either in its census or public health data.

Korea has no official estimate of how many LGBTQ+ people live in the nation, how diverse the LGBTQ+ community is, how many of them have walked down the aisle unofficially or what social problems they face that need to be addressed, the advocates said.

“The country has no estimate to see if sexual minorities even exist,” Rep. Jang Hye-young of the minor progressive Justice Party told The Korea Herald.

Jang, who proposed a set of rules and revisions in pursuit of marriage equality in May, claimed the lack of statistics about the LBGTQ+ community is making it challenging for her to make the case for the marriage equality bill.

“There is no language for public discourse about such a phenomenon,” Jang said. “Public data that no one could neglect must be in place to start a public debate on why same-sex couples should be given legal marriage status.”

Jang argued that a lack of legal framework has impeded the provision of the necessary state support or protection. For example, Korea has failed to guarantee a same-sex partner’s medical guardianship and to recognize same-sex partners in visa issuance for foreign spouses, among other cases.

Additionally, the government’s failure to produce LGBTQ+ statistics hampers timely policy interventions in response to problems that arise from discrimination or hatred targeted at them, job insecurity and other issues.

“Now, it seems the country does not want to put a ‘name tag’ on” sexual minorities, Jang said.

Older generation changing

But there is a silver lining, as changes in public perception toward same-sex marriage are slowly emerging.

According to biennial surveys by Gallup Korea, opponents of same-sex marriage outnumbered supporters as of May this year, but the gap has been narrowing.

The gap between supporters and opponents stood at 50 percentage points in 2001, but decreased to 21 percentage points in 2014 — when 35 percent of respondents were in favor and 56 percent were opposed to same-sex marriage. This gap has again halved over the course of the past decade, with 40 percent in favor and 51 percent in opposition in this year’s survey.

“Korea is still a country where the family-oriented culture and the concept of traditional gender roles are stubbornly fixed,” said Cha Hae-young, a district council member of Mapo-gu in Seoul who is Korea’s first openly LGBTQ+ elected official.

But the continued publicity campaigns have led to “changes in the public perception (toward sexual minorities) over time in the past few decades, attracting more allies who stand up for their rights,” Cha added.

In particular, among the older generation 10 years ago, opponents were more likely to have switched sides on marriage equality compared to younger people.

Same-sex marriage supporters accounted for 38 percent and 23 percent, respectively, of those in their 50s and 60s this year. Both of those figures have showed significant uptrends compared to a decade ago. The proportion of supporters in their 40s and 50s in 2013 — the same age group 10 years ago — came to 19 percent and 7 percent, respectively, indicating support for marriage equality in those age groups has risen twofold and threefold, respectively.

This contrasts with the younger generation. Among 20-somethings in 2013, 52 percent were in favor. Ten years on, the number for 30-somethings was little changed at 53 percent. A similar trend was observed for 30-somethings in 2013, whose ratio of supporters climbed up by 5 percentage points to 45 percent 10 years later.

“It’s interesting to see how those in their 40s and 50s in 2013 changed their mind dramatically,” Jang of the Justice Party said.

Reversing course

Jang’s new set of bills to allow LGBTQ+ people to attain marriage status within the legal framework is ready to be tabled for discussion among lawmakers at the National Assembly later in July. One of the bills is the first of its kind to revise the Civil Act by clarifying that a marriage shall take effect by reporting by “either a heterosexual couple or a homosexual couple.”

But one of her other bills — a Korean equivalent to Germany’s Act on Registered Life Partnerships — is already facing backlash from conservative figures.

Kim-Jho Gwang-soo, an openly LGBTQ+ film director, speaks at a discussion forum on a set of bills to legalize same-sex marriage, at the National Assembly on June 7. (Yonhap)

As per the similar bill earlier proposed by Rep. Yong Hye-in of the minor Basic Income Party this year, Justice Minister Han Dong-hoon also voiced concerns that the bill — aimed at having a nonmarried life partner entitled to policy protections and legal rights that could be as much as those of a married couple — was proposed “without gaining proper consent among citizens.”

On the other hand, pro-LGBTQ+ moves can be seen as overshadowed by the rhetoric and actions of authorities in opposition, and there are no specific provisions against hate speech, with an anti-discrimination bill proposed in 2020 still pending at the Assembly.

In the latest occasion, conservative Daegu Mayor Hong Joon-pyo has remained adamant over the past weeks in ramping up his offensive against the city police, after they prevented city officials from blocking a pride parade that had been registered with the law enforcement authorities. Physical wrangling between the two sides lasted for hours at the venue. Hong denied being anti-LGBTQ+, but he also claimed they had no right to occupy the street and block traffic in Daegu’s shopping district.

Seoul’s municipal government, meanwhile, did not grant LGBTQ+ organizers permission to use Seoul Plaza to hold the Seoul Pride parade there this year. Instead, Seoul City Hall, controlled by conservative Mayor Oh Se-hoon, opted for a Christian group to use the public space for its own “concert for the young generations’ well-being.”

This effectively forced Seoul Queer Culture Festival organizers out of Seoul Plaza for the first time since 2015.

A clash between LGBTQ+ supporters and the Christian-affiliated group on July 1 is widely anticipated, as Yang Sun-woo, head of the Seoul Queer Culture Festival organizing committee, has said the pride parade plans to march through Seoul Plaza from Euljiro, where it was relocated.

“We have fallen short of the change of mind among policymakers or lawmakers,” said council member Cha.

“The political circle has lacked research pertaining to issues of same-sex marriage and anti-discrimination. and many citizens still have no clue of what the concept of ‘sexual minorities’ is. It is regrettable to say that neither the government nor the parliament is trying to narrow the awareness gap.”

A South Korean holds a rainbow pride flag at the Korea Queer Culture Festival in front of City Hall on June 1, 2019, in Seoul. The annual festival promoting LGBTQ+ rights had occasionally been disrupted by anti-LGBT groups in the past, although homosexuality is not illegal in the country. (Getty Images)

“Public figures have been failing to affirm nondiscrimination, and moves to tackle discrimination have made slow progress, despite anti-discrimination clauses in the Korean Constitution and law,” said Hong Sung-soo, a law professor at Sookmyung Women’s University.

“Should it become law, the anti-discrimination bill will serve as an affirmation that discrimination will not be tolerated in Korea. But the reality here is that the bill has been pending for years.”

The biennial Gallup poll also indicated polarizing views among young Koreans. Support for legalization of same-sex marriage among people in their 20s dropped to 64 percent as of May, compared to 73 percent two years prior.

The shift stems from a significant change in perception among young men in Korea, prompted by an anti-feminism movement in 2021 based on the notion that men are facing “reverse discrimination” in favor of women and minorities.

Of men in their 20s, 52 percent responded in the survey this year that they support same-sex marriage, down from 65 percent in 2021. Also, 63 percent of 20-something men perceive a romantic partnership between same-sex couples as “love,” down from 82 percent in the 2021 poll.