December 12, 2023

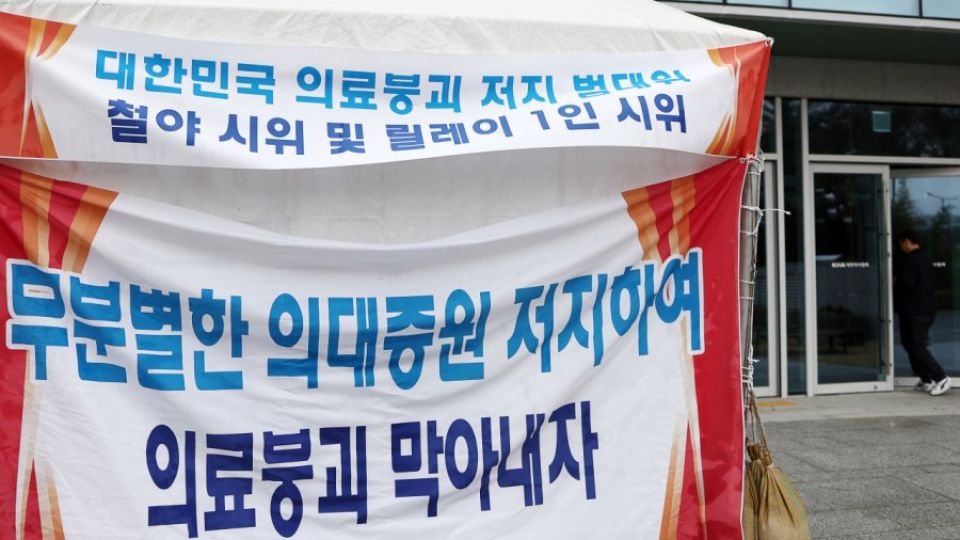

SEOUL – The Korean Medical Association, South Korea’s largest group of medical doctors, began collecting votes on Monday on whether they should launch a general strike against the government’s plan to expand the medical school enrollment quota.

The organization will collect votes until Dec. 17, and announced that doctors will stage a mass rally on the same day near Gwanghwamun in central Seoul. The majority of the association’s membership consists of doctors running their own clinics.

Ahead of such a notice, the Ministry of Health and Welfare declared that the country was at a “caution” level — the first stage out of its four-tier system — for a health care crisis on Sunday, and formed an emergency response team. Under the standard manual for possible health care disasters, this is a stage in which the government checks whether the public can access proper medical treatment in case of strikes or hospital closures, and sets up a cooperation system with related organizations.

The Health Ministry assured that there would be no confusion or inconvenience at medical sites, and called the KMA’s decision “inappropriate,” especially when the negotiation between the two are still underway.

“We will dutifully continue talks with the medical community, but the government will respond decisively with the authority and responsibility granted against any illegal actions,” Health Minister Cho Kyu-hong said at the Sunday meeting.

According to the KMA, the results of the vote are unlikely to be disclosed to the public. Though the majority of its members agree to the collective action, a nationwide medical strike will not take place right away. The KMA stressed that the purpose of the vote lies in gathering the opinions of its members.

“This doesn’t mean we will go on a strike right away. It means we’re getting members’ approval about whether strikes could be a possible option if we fail to reach a settlement in talks with the government,” the KMA was quoted as saying in local reports.

If doctors take collective action, such as taking a joint leave of absence, they can be punished for refusing to treat patients under the Medical Service Act. In the case of illegal closures, the government can deliver a business resumption order to owners of closed medical institutions. Violators of the order can face criminal charges along with administrative penalties, which include 15 days of business suspension.

However, there is widespread speculation that doctors are taking a more cautious stance amid rising concern among the public over doctor shortages.

There are voices within the medical community that it would be difficult to take action in a situation where there is clear public and political support in favor of raising enrollment at medical schools.

In a poll conducted by the Korean Healthcare Workers’ Union on some thousand Korean nationals in November, 82.7 percent of respondents said that medical school enrollment should be expanded to increase the number of doctors.

Such a clash comes after the government unveiled its plan to raise the annual enrollment quota for medical schools by more than 1,000 from the current 3,058 to address a doctor shortage and to improve public health services. Specialties such as pediatrics, obstetrics, cardiothoracic surgery and neurosurgery have faced significant operational crises due to doctor shortages, affecting patients in regional areas.

Doctors have opposed the government’s plan, claiming that the government has simply sought to raise the quota rather than exploring ways to better allocate physicians and boost compensation, which will compromise the quality of medical education and services.