February 3, 2025

HONG KONG/SHENZHEN – At the Shenzhen Civic Centre, dazzling patterns formed on towering skyscrapers, lit by more than a million LED light panels that bathed the city’s skyline in brilliant colours.

“That’s just like Hong Kong,” a woman exclaimed in Cantonese as the area lit up in unison at 8pm on a recent Friday evening, flashing in sync to upbeat music.

The 15-minute spectacle, which is projected on more than 40 buildings in the area, runs thrice nightly on Fridays and Saturdays in China’s Silicon Valley in southern Guangdong province.

The Shenzhen light show, launched in 2018 to celebrate China’s 40 years of reforms and opening up, is often compared with a similarly iconic performance in neighbouring Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s Symphony of Lights show has been a tourist staple since 2004.

For 10 minutes from 8pm every evening, more than 40 buildings illuminate the city’s skyline with flashing LED panels, sweeping searchlights and projected laser beams “dancing” in rhythm to an East-West fusion of orchestral music.

But the Hong Kong show, which two decades ago was listed in the Guinness World Records for being the world’s largest permanent light and sound show, now appears to pale in comparison to its neighbour’s flashier and more sophisticated display.

It is symbolic of how the two cities’ roles have evolved in recent years.

Once a rural backwater that looked up to its richer, savvier neighbour across the border, Shenzhen underwent rapid development in the past four decades and flipped the power dynamics.

Today, it is with much admiration and some self-reproach as Hong Kong regards its northern neighbour’s technological advancements and economic achievements.

But within the Greater Bay Area (GBA), the reality is that both cities will need each other in order to have sustainable growth going forward.

The GBA refers to the region comprising the semi-autonomous cities of Hong Kong and Macau, and nine cities in Guangdong, including Shenzhen and Guangzhou.

Shenzhen is now home to many of China’s biggest tech giants, like telecommunications conglomerate Huawei, video gamemaker Tencent, electric carmaker BYD and dronemaker DJI.

It is among the country’s top three growth-engine cities, accounting for 2.7 per cent or 3.46 trillion yuan (S$652 billion) of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2023 – bested only by Shanghai’s 3.7 per cent and Beijing’s 3.5 per cent.

And it is expected to have performed even better in 2024, with its GDP growth in the year’s first three quarters already surpassing those of Beijing and Shanghai.

Hong Kong, meanwhile, ranked as the world’s fifth most competitive market in 2024, after Singapore, Switzerland, Denmark and Ireland. The ranking by IMD Business School in Switzerland is based on four main factors: economic performance, government efficiency, business efficiency and infrastructure.

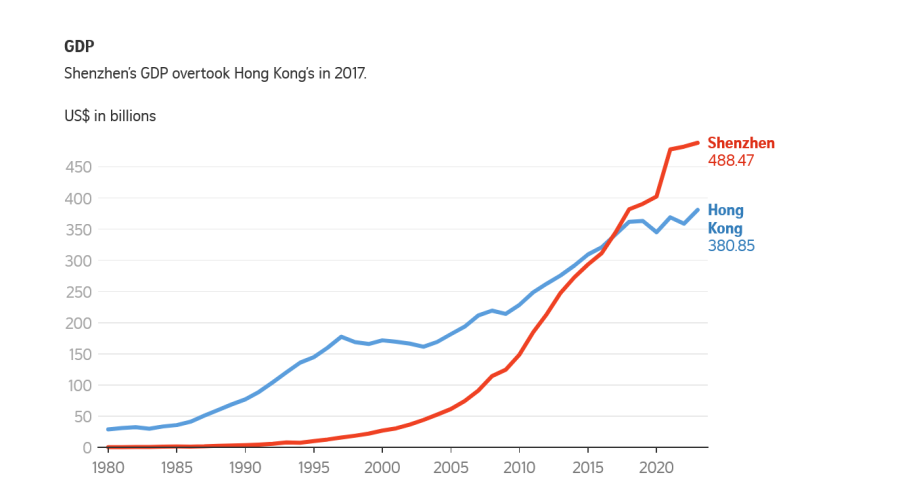

But its GDP – once 500 times that of Shenzhen’s before the 1980s – has lagged behind the latter’s since 2017, standing at HK$2.98 trillion (S$517 billion) in 2023. And its port, once the world’s busiest, has fallen in the rankings as more trade is routed through Shenzhen and other Chinese ports.

In terms of living standard, however, Hong Kong’s is higher than that of Shenzhen with a per capita GDP of US$53,000 (S$71,852), almost twice that of Shenzhen’s US$27,000.

SOURCE: HONG KONG CENSUS AND STATISTICS DEPARTMENT, SHENZHEN MUNICIPALITY BUREAU OF STATISTICS, BANK FOR INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENTS; GRAPHICS: THE STRAITS TIMES

Seeds of change

Separated only by a narrow river, Hong Kong and Shenzhen have been held up against each other for contrast and comparison since China’s opening up four decades ago.

Historically, Hong Kong has been known as the “Pearl of the Orient”, a success story that most other Chinese cities could once only aspire to.

From the 1950s to 1970s, it was the prosperous port city to which mainland Chinese people – living in poverty under the planned economy of the Communist Party – fled in droves, risking life and limb swimming in dangerous waters or trudging in the deep of the night across the border in desperate hope of a brighter future.

Even towards the turn of the century, when China had grown more prosperous, it continued to draw ambitious young mainlanders seeking high-paying jobs.

“Hong Kong was regarded as a place full of opportunities for people who were capable and determined, no matter their origin,” the city’s first mainland born and bred minister, Professor Sun Dong, recalled in an interview with The Straits Times in 2022.

Prof Dong, who is the Secretary for Innovation, Technology and Industry, was explaining why he chose to pursue his doctoral education in robotics and automation in the financial hub over 30 years ago.

In a separate interview with his alma mater, he recounted receiving his first monthly scholarship stipend of more than HK$9,000 at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 1994, compared with the “less than 100 yuan” he got on the mainland.

The stipend would have amounted to over 10,000 yuan according to the exchange rate at the time.

“It spoke volumes about the discrepancy in living standards between Hong Kong and the mainland at the time,” he said.

The first seeds of change were planted in the late 1970s, when China decided to make Shenzhen one of the country’s first four “special economic zones” (SEZs).

The Cultural Revolution, which ended in 1976, had crippled the Chinese economy.

This, alongside the unabating outflow of Chinese despite a heavily guarded border, made the leadership realise that it had to find new ways to grow the economy.

In 1980 and 1981, Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Shantou in Guangdong province, and Xiamen in Fujian province, became the country’s first four experimental fields for economic reform.

Picked for their respective proximity to Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, the aim of the SEZs was to learn from these more open, export-oriented economies, with Hong Kong and Macau at the time being colonies of Britain and Portugal respectively and Taiwan a self-ruled island that was and is claimed by China.

Hong Kong and Macau were returned to China under the one country, two systems political framework in 1997 and 1999 respectively.

The SEZs were given unprecedented leeway to experiment with market-oriented policies to attract more businesses and investments to the region.

Learning from the best

Chinese officials studied established models around the world for reference, travelling to places such as Singapore, Ireland and Hong Kong.

Hong Kong, in particular, played an indelible role in its northern neighbour’s transformation.

As Shenzhen, which began as a clutch of villages and farmland, sought to navigate an unfamiliar capitalist world in the 1980s and 1990s, it looked to the wealthy business hub for inspiration.

“In those early years (of the SEZ), the thinking of the people in Shenzhen and their ways of doing business were to a large extent affected by those in Hong Kong,” Professor Anthony Cheung, a former Hong Kong minister who is now chair professor and adviser in public administration at the Education University of Hong Kong, told ST.

Then, the British outpost’s laissez-faire economy was booming across sectors, including in its asset markets, finance and banking, manufacturing and personal consumption.

Its movie and music industries were flourishing, too, with well-loved stars like Leslie Cheung and Aaron Kwok bringing the city’s soft power to places far beyond its shores.

In time, Hong Kong became a key source of investments, know-how and infrastructure funding for Shenzhen, according to Associate Professor Zhou Taomo, a historian at the National University of Singapore.

The financial hub gave Shenzhen unfettered access to the capital, talents, ideas and technology that the new SEZ needed to carve out a niche for itself.

Shenzhen, meanwhile, picked up the slack in industries, such as manufacturing, that Hong Kong was shedding as it upgraded its own economy.

“Hong Kong was essential not just to Shenzhen’s development, but also to China’s overall reform and opening up,” Prof Zhou, who grew up in Shenzhen and is writing a book about its development, told ST.

Many of Shenzhen’s early external investors were from Hong Kong. Eager to relocate their factories to wherever production was cheaper, their influx of capital helped to create jobs and stimulate the economy.

More importantly, these enterprising businessmen also brought with them ideas for economic reforms.

These ideas, which were quickly and widely implemented across Shenzhen, went a long way towards industrialising the mainland city – and later the rest of China.

One of these Hong Kongers, the tycoon founder of the 1970s iconic handbag and shoes brand Millie’s Group, Mr Alan Lau, played an important role in improving Shenzhen’s labour efficiency.

Officials allowed his Bamboo Garden Hotel – the city’s first foreign-invested hotel, which opened in 1981 – to pioneer the hiring of workers via contracts, after he complained that the prevailing system of iron rice bowls, where people basically had their jobs for life, was bad for business.

The Shenzhen Stock Exchange, set up in 1990, emulated Hong Kong’s century-old bourse.

“When establishing Shenzhen’s capital market, policymakers systematically translated the financial regulations of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, which served as a key reference,” said Prof Zhou.

Today, Shenzhen’s stock exchange is one of the 10 largest bourses in the world by market capitalisation, narrowly trailing the Hong Kong exchange as at December 2024.

Hong Kong’s tycoons also helped to build some of the key infrastructure projects serving Shenzhen.

Property developer Hopewell Holdings’ Mr Gordon Wu, for instance, was instrumental in helping Shenzhen build a power station to fix electricity shortages in its factories, as well as a highway to link the city to the provincial capital of Guangzhou.

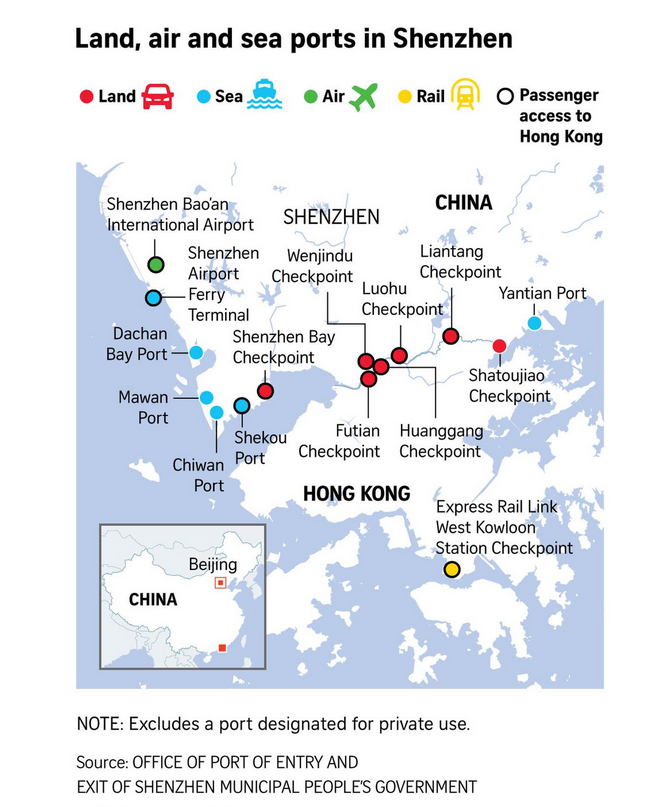

In time, railways, ports and an airport sprang up, boosting Shenzhen’s connectivity and turning it into a logistics hub in its own right. This reduced its reliance on Hong Kong as a gateway to the world.

Dentist-entrepreneur Albert Lam, 65, who in the 2000s ran a business exporting dentures and crowns custom-made in Shenzhen to foreign buyers via Hong Kong, recalled that by 2007, it became more efficient to operate directly out of the mainland city.

“China caught up, and the logistics in Shenzhen became better than doing it through Hong Kong,” said the native of the financial hub, who moved to Shenzhen in 2007, where he still lives and works as a dentist and developer of dental tech.

GRAPHICS: THE STRAITS TIMES

Shenzhen rises

Shenzhen’s success did not come about just by following the well-trodden paths of other prosperous cities. It also blazed its own trail. The manufacturing powerhouse has come to be known as fertile ground that spawned industry leaders in sectors spanning telecommunications and drones to electric vehicles and mobile games.

The concentration of tech companies in Shenzhen has given it its prized status as “the Silicon Valley of China”.

How did it manage to catapult itself up the value chain, from just a manufacturing hub to a tech powerhouse, in a little more than two decades?

One contributing factor is intervention from the city’s government, which identified early on the need to develop high-tech industries to drive the economy.

This happened during a difficult time for Shenzhen around the late 1990s to early 2000s, according to the former Hong Kong minister Prof Cheung.

“Back then, Shenzhen was keen to deepen its relationship with Hong Kong, but Hong Kong preferred to focus on further developing itself as a major international financial centre like London and New York,” he said.

“Meanwhile, because the whole of China was opening up and undergoing economic reform at the time, being an SEZ was no longer special. There was a whole debate as to whether there was a future for Shenzhen.

“So Shenzhen, by way of its circumstances, had to find its own niche. And it put its bet on innovation and technology,” Prof Cheung explained.

The Shenzhen government built high-tech industrial parks and doled out incentives to reel in tech firms.

They positioned the city as an innovation hub, holding China’s biggest technology fair – the China Hi-Tech Fair – every year since 1999.

Shenzhen’s leaders also recognised the importance of building a talent pipeline for its tech firms, and stepped up the establishment of universities.

The first of the city’s universities – Shenzhen University, founded in 1983 – played an important role in training the city’s future technopreneurs. The founders of Tencent, including chief executive Pony Ma, are among its alumni.

From the late 1990s to early 2000s, city officials brought in top schools such as Peking University and Tsinghua University, which set up satellite campuses in the city. They also established the Shenzhen Institute of Information Technology.

Shenzhen’s innovative edge also grew organically, out of its migrant-friendly outlook and mature manufacturing ecosystem.

“To me, Shenzhen is China’s most open city in terms of its thinking, culture and way of doing business,” Assistant Professor Zhang Yuqun, of the Southern University of Science and Technology’s (SUSTech) Department of Computer Science and Engineering, told ST.

The city’s open-minded culture and array of innovative firms are a draw for tech talents from across the country, said Prof Zhang, who relocated to Shenzhen in 2017 after eight years in the US.

Shenzhen’s extensive agglomeration of engineers and components across the supply chain is also what makes it an attractive destination for entrepreneurs, according to Dutch national Henk Werner, who runs Shenzhen-based start-up accelerator TroubleMaker.

The city is home to the world’s largest electronics market in Huaqiangbei, a major electronics manufacturing hub, where prototypes can be made at a fraction of the time and cost needed elsewhere, Mr Werner told ST.

The story of why the founder of major dronemaker DJI had relocated from Hong Kong to Shenzhen is telling in terms of the competitive advantage enjoyed by the latter city.

Hangzhou native Frank Wang had been building flight controllers in his dorm room at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, where he had been studying electronics engineering from 2003.

However, he failed to find a way to mass produce his innovations in Hong Kong.

In 2006, he decided to move to Shenzhen, attracted by its start-up-friendly policies, to start DJI.

“I could only design, I couldn’t produce (in Hong Kong),” Mr Wang said in a 2015 interview with Chinese-language news magazine Yazhou Zhoukan.

“We had to source even a screw from outside. (But) the division of labour provided by suppliers here (in Shenzhen) guarantees that what we get is better and cheaper.”

Today, DJI is the world’s biggest dronemaker, controlling more than 90 per cent of the global consumer market.

The company turned down a request for Mr Wang to be interviewed for this article.

It is not realistic for Hong Kong to try to compete with other cities in terms of manufacturing goods for mass production, Mr Peter Mok, general manager at the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Youth Innovation and Entrepreneur Hub (Ehub), told ST.

He is based in Qianhai, a commercial development zone in Shenzhen, providing support for start-ups seeking to enter the mainland market via Hong Kong, as well as Chinese tech firms trying to expand globally through the financial hub.

Mr Mok, former head of Greater Bay Area with the Hong Kong Science and Technology Parks Corporation, said that from his experience in both cities’ start-up scene, Hong Kong was a good nurturing ground to translate innovative ideas into reality in the form of start-ups, while Shenzhen was the best place for such small tech firms to scale up after initial success.

“For tech firms in the region, Shenzhen is the nearest and cheapest place to move production to, with a highly skilled and very young labour force. Engineers, scientists and programmers with strong technical skills are in abundance here,” he said.

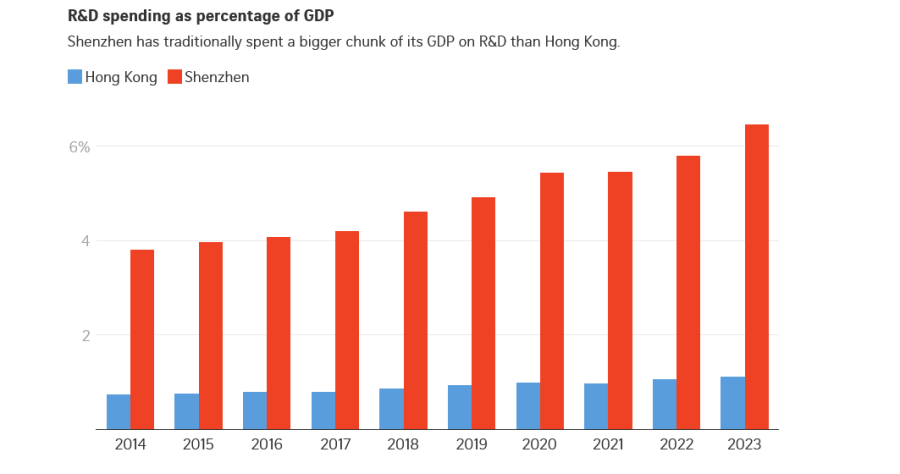

SOURCE: HONG KONG CENSUS AND STATISTICS DEPARTMENT, SHENZHEN MUNICIPALITY BUREAU OF STATISTICS; GRAPHICS: THE STRAITS TIMES

Hong Kong’s strategic missteps?

DJI founder Mr Wang’s difficulty in finding a way to mass produce his innovations in Hong Kong stemmed in part from strategic decisions that the city made over the years.

Around the 1990s, Hong Kong’s economy gradually transitioned from a manufacturing-based one to a more service-oriented one, focused on financial and professional services.

The shift came about after the city’s labour and production costs rose as its economy boomed, leading manufacturers to seek out cheaper production bases elsewhere, particularly in mainland China.

But rather than moving its manufacturing up the value chain – such as upgrading factories’ technological capabilities or producing advanced, unique or critical components – Hong Kong chose to almost entirely hollow out the industry.

Former industrialists, like tycoon Li Ka-shing, shut their factories and ventured into more profitable businesses such as real estate and retail.

At the same time, Hong Kong’s elites were also aware that innovation and technology (I&T) could become an important new niche and economic driver.

But the city’s favoured formula of laissez-faire governance would prove a stumbling block in this aspect, losing Hong Kong its vital first-mover advantage.

Hong Kong’s nascent I&T industry was in the mid-90s identified by the government and academics as a critical sector to develop after economic data pointed to a need for a new growth engine, Professor Tang Heiwai, associate dean of external relations at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) Business School, told ST.

Hong Kong acted by setting up the Science Park in Shatin and Cyberport in Pok Fu Lam in the early 2000s to spur tech research and incubate start-ups.

“The idea was to create a network of I&T stakeholders from universities, the scientific community and industrial sector, while the government provided land and facilitated the process,” Prof Tang said.

But a lack of strategic direction from the largely non-interventionist government, and a lack of resources allocated to the endeavour resulted in missed opportunities.

Local developers, unfamiliar with a tech hub’s unique requirements, turned to what they knew best. They built luxury homes and costly office spaces on those sites, whose locations were already deemed inconvenient due to limited transport infrastructure in the vicinity.

The network envisioned hence failed to materialise as start-ups there faced high rents, and low commercial and manufacturing integration to make and promote their products, and often stayed afloat only by chasing government funding.

On the other hand, Shenzhen – like Silicon Valley in the US – succeeded because it enabled a tight feedback and funding loop between academia and industry, allowing start-ups to enjoy low barriers to entry and a low cost of failure, from cheap rents to proximity to a plethora of talent and other opportunities in the region.

Leaning on the Greater Bay Area

The reversal in the fortunes of both cities has evoked “great anxiety” in Hong Kong over its future, according to Prof Cheung.

To generate new drivers for the economy, the city’s officials have been leaning more heavily into the GBA network of cities, an initiative launched by the mainland in 2019 to boost connectivity and thereby growth in the area.

“The larger picture is that Shenzhen and Hong Kong will never replace each other,” he said, adding that each city has unique selling points that are complementary within the GBA network.

For Hong Kong, it is the one country, two systems framework that allows it to perform functions that mainland cities cannot.

Even as Beijing has tightened its control over the city following pro-democracy protests there in 2019, Hong Kong still retains its own immigration, monetary, fiscal and taxation systems, as well as freedoms different from that of mainland China.

Shenzhen, meanwhile, is a hub of high-tech manufacturing and innovation from which the mainland market and business networks are easily accessible – but less so the outside world.

“The GBA concept was always an outward-looking plan (to connect with the rest of the world),” Prof Cheung said. “In the plan, Hong Kong and Macau are the cities with established links to the international world, while Shenzhen, Guangzhou and the other cities provide the links to the rest of mainland China.”

Ehub’s Mr Mok noted that the Shenzhen-Hong Kong-Guangzhou tech corridor within the GBA was ranked second among the world’s top 100 science and tech clusters in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

The Tokyo-Yokohama cluster took first spot in the index published by the World Intellectual Property Organisation.

“Our tech corridor is one of the world’s best because of how our cities complement each other,” he said.

“Hong Kong, for example, has five universities that rank within the world’s top 100 list, while Shenzhen has none despite its other strengths. These institutes are renowned for their strong foundation in translational research (the practical application of basic scientific discoveries) – an edge for Hong Kong that cannot be easily challenged or replaced.”

It is for these reasons that deeper integration with the GBA is a boon for Hong Kong, Associate Professor Billy Mak of the Hong Kong Baptist University’s Department of Accountancy, Economics and Finance told ST.

It is a critical step for the city to ensure sustainable growth and retain its relevance in the region and beyond, contrary to a widely perpetuated notion that becoming more intertwined with mainland China would mean Hong Kong losing its strengths to the mainland, he said.

“While Hong Kong has traditionally been very strong in R&D in advanced technologies, it is weak in commercialising that research – which Shenzhen is good at,” Prof Mak said, referring to DJI founder Frank Wang’s experience.

“Greater cooperation with the GBA will open up access to the manufacturing points and supply chain that Hong Kong needs to convert its academic output into products that can be mass produced and sold.”

“The region will also provide a far bigger test market to promote these products,” he added.

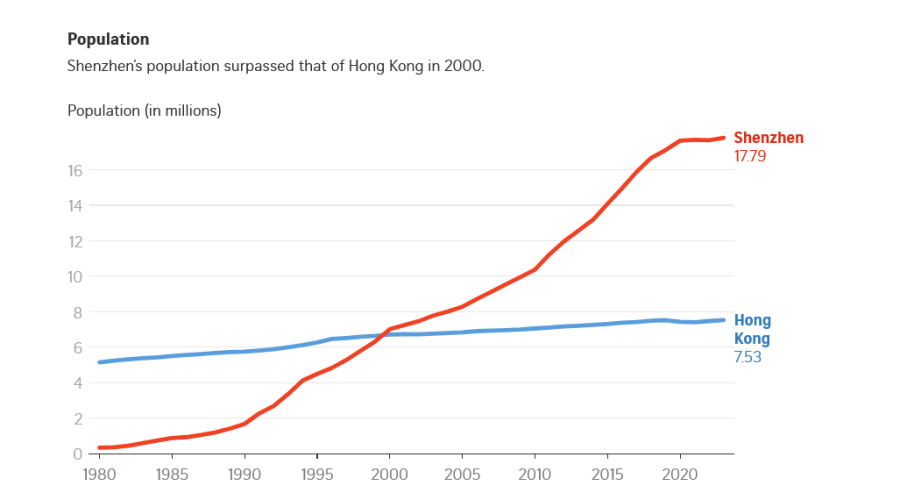

The GBA’s population stands at 86 million, 11 times that of Hong Kong’s 7.5 million. Shenzhen’s population is around 17.8 million.

SOURCE: HONG KONG CENSUS AND STATISTICS DEPARTMENT, SHENZHEN MUNICIPALITY BUREAU OF STATISTICS; GRAPHICS: THE STRAITS TIMES

As for Shenzhen, Hong Kong’s role as an international financial centre and source of foreign currency remains useful for the tech hub to keep pressing its advantage.

Hong Kong is a source of financing for mainland companies, whose demand for investments has increased amid a slowing economy and a retreat of foreign funds in the mainland, said Mr Joseph Mak, a partner and co-president at Bohan Financial Group in Hong Kong.

In the mainland, “there are not many (investment) funds and the flow of financing is low, especially for start-ups and some private companies”, he said.

Mr Mak is also dean of the Asia-Pacific ESG Strategy Research Group, a consultancy which has offices in Shenzhen and Hong Kong and helps to match mainland companies with investors in the financial hub.

Hong Kong and Macau accounted for more than 90 per cent of foreign investments in Shenzhen in 2022, official data showed.

Since 2021, Shenzhen has also issued offshore bonds worth 22 billion yuan in Hong Kong to raise funds for government spending and infrastructure projects.

The Hong Kong bourse remains an important source of capital for Chinese companies as it becomes more difficult to launch initial public offerings (IPOs) in the mainland with regulators having tightened listing requirements there.

In 2024, IPOs in Hong Kong raised US$10.7 billion (S$14.5 billion) in funds, compared with US$3.7 billion in Shenzhen and US$4.6 billion in Shanghai, according to figures from accounting firm EY.

SOURCE: EY; GRAPHICS: THE STRAITS TIMES

Chinese companies also use Hong Kong as a receptacle for foreign funds, and a door to overseas expansion.

Mr Ray Wang, 36, a consultant for cross-border e-commerce companies in Shenzhen, said that many of his clients open bank accounts in the financial hub to receive payments from buyers around the world. “The mainland has foreign exchange controls, and it is difficult to transact directly with buyers abroad.”

Some of these companies also use Hong Kong as a venue to meet foreign clients, he added, as the city is more accessible for foreign passport holders.

Ultimately, it is about growing the economic pie, according to Hong Kong Baptist University’s Prof Mak.

“At the end of the day, Hong Kong and Shenzhen’s roles relative to each other are complementary, not necessarily competitive,” the economist said. “As long as we collaborate and derive lessons from each other, our pie will only get bigger”.

- Magdalene Fung is The Straits Times’ Hong Kong correspondent. She is a Singaporean who has spent about a decade living and working in Hong Kong.

- Joyce ZK Lim is The Straits Times’ China correspondent, based in Shenzhen.