November 21, 2022

JOHOR BAHRU – Winning 18 parliamentary seats or more in Johor would have been ideal for Pakatan Harapan (PH), but grabbing 14 out of 26 seats will do for now, said the coalition’s winning Tebrau candidate Jimmy Puah.

Reaching out to residents and younger voters “had surely helped us gain a bit”, said Mr Puah, a lawyer and Johor vice-chairman for Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), a key component in PH.

Of PH’s campaign messaging promising a caring government free of corruption if it gets the mandate, he said: “I think the younger voters do get it. But at the same time, I don’t think they’ll automatically vote for us because there’s another political alliance (Perikatan Nasional) who is also saying the same things.“

The PH alliance, which includes the Democratic Action Party (DAP), may have fallen short of the 18 seats it was aiming for in Johor but Mr Puah said he was proud that the state had, for a second time, become a PH fortress, especially in South Johor.

PH held 11 of the state’s 26 seats before Parliament was dissolved.

After Saturday’s poll, Perikatan Nasional (PN) lost a seat to hold on to two parliamentary seats, while Barisan Nasional (BN) gained a seat to make it nine, and youth-centric party Muda took one.

Mr Puah added: “Beyond the party, I would like to say Johor is the last bastion of moderate politics… (But) I don’t feel that the race issue has been removed entirely from the election campaign.”

Johor DAP chairman Liew Chin Tong had earlier told The Straits Times that PH’s strategy was to target swing seats and younger voters, who may not have formed any political allegiances. It was also a priority to encourage Malaysians abroad to return to vote. The swing seats were in Johor’s multiracial, Malay-majority and semi-urban areas.

Mr Liew had said: “If there’s a high turnout, higher chance for PH. If the turnout is below 50 per cent, then it is a gone case (for PH).”

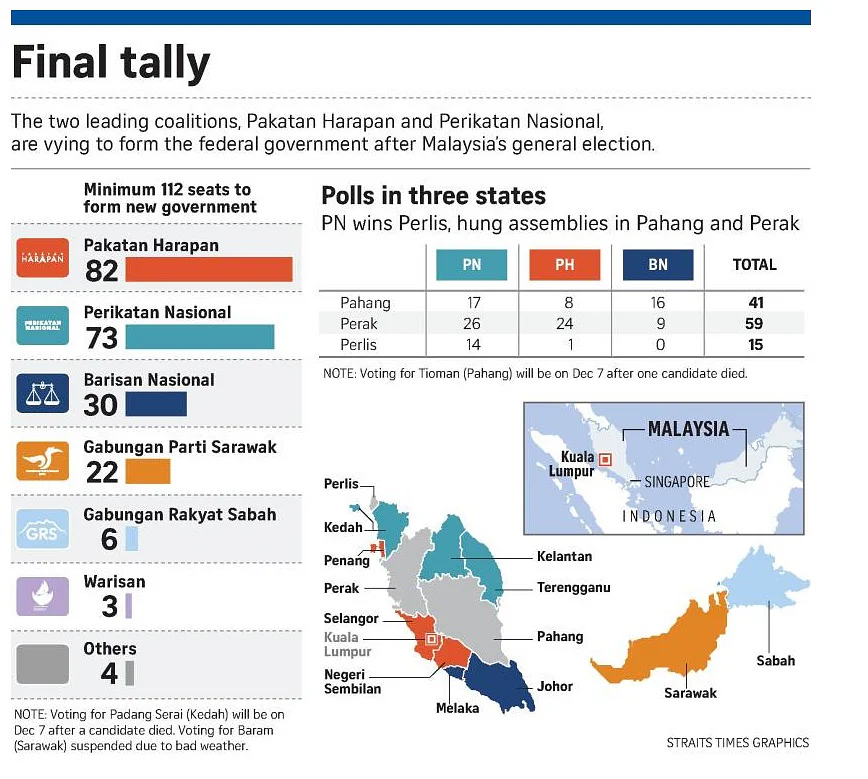

Johor had been a BN stronghold until the Umno-led ruling coalition was overthrown in the landmark 2018 election, which saw PH come to power after securing 122 seats in Parliament. While BN managed to cling on to 79 seats in 2018, its slide continued in 2022’s general election, where it won just 30 seats.

Dr Francis Hutchinson, coordinator for the Malaysia studies programme at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, said: “I think BN’s internal dysfunction, particularly Umno’s inability and reluctance to soul-search and undergo deep reform following the 2018 loss, really came home to undercut its political position.”

What chipped at BN’s credibility at the recent 15th General Election were its candidate selection, slow campaigning and the uncertainty of who was leading the fight, he added.

While Dr Hutchinson said PH is a very stable part of the country’s political system, the real “structural shift” was not so much PH but PN, which exceeded his expectations by giving an alternative that offered the same focus on religion, ethnic issues and supposedly with less corruption.

One of the surprises from the election showed that politics is changing, with social media becoming the platform of choice for savvy parties, unlike the traditional grassroots politics that Umno is good at, said Dr Hutchinson.

Credit must be given to PN for running a smooth online campaign, especially targeting urban Malays, Mr Puah conceded.